09. Appendices

Appendices

The appendices provide supporting materials and extended documentation that complement the main analysis. Appendix A presents ethical materials and recruitment documentation; Appendix B expands on methodological tools and data excerpts; Appendix C includes correspondence and case studies; Appendix D documents learning design artefacts such as maker types and side missions; and Appendix E links to the technical toolkit and online resources.

Appendix V: Vignettes

This appendix presents a set of vignettes that capture bounded episodes of game making activity observed during the study. Each vignette has been developed from synchronised screen-capture and 360-degree video recordings, with additional details drawn from field notes and participant interviews. The vignettes illustrate the dynamics of collaboration, problem solving, and facilitation discussed in Chapters 5, 6 and 7, and form part of the evidence base for the analysis of contradictions and participant agency.

The following vignettes illustrate specific episodes of participant activity discussed in the thesis. Each includes a transcript or activity log followed by a short reflective commentary. Vignettes vary in internal structure depending on analytic purpose. Some include micro-analytic tables or multiple commentary sections where required to support specific theoretical claims. In transcripts, ‘Mick’ refers to the facilitator role as enacted in situ; reflective commentary adopts the researcher voice. Some vignettes are extended to preserve interactional continuity where fragmentation would obscure the learning process. Interpretations presented in the vignettes are informed by triangulation across multiple data sources, including post-session participant interviews and reflective discussions. Where descriptions of challenge, frustration, or engagement are included, these are grounded in participants’ own subsequent accounts of their experiences, rather than inferred solely from observation as discussed in Chapter 4.

INSERT THEM HERE.

Appendix A: Ethics and recruitment

Appendix A contains the documentation submitted to and approved by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Faculty Ethics Committee. It includes participant information sheets, consent materials, and recruitment correspondence used during the Game Making Club. These materials show how participants were informed about the study, how consent and withdrawal were handled, and how ethical safeguards were maintained throughout. The documents relate directly to the methodological framework described in Chapter 4.

A2: Game Making Club follow up email

My name is Mick Chesterman. I am a tutor and PhD student in the Manchester Metropolitan University Faculty of Education. I am looking for families to take part in a Game Making club to learn how to make video games together.

The weekly game making activities start on take place on ___________ and the Manchester Met Brooks campus and will last until __________________.

These activities are part of a study looking at collaboration, creativity and problem solving in a family learning environment. Taking part in the study will involve some of the sessions being recorded and some interviews with you about your experiences. More details will be provided as part of a fuller participant information sheet.

If you do not wish to be a part of this study that’s not a problem. You should still apply to take part as one version of the club will not be a part of the study. This version of the club will undertake equivalent activities.

To register your interest in taking part. Please email me on m.chesterman@mmu.ac.uk

Many Thanks

Mick Chesterman.

Appendix A3: Full Participant Information Sheets

Investigating the Potential of Family Game Making to Support Collaborative Production: Participatory research with Families

A3a. Information Sheet for Parents

You and your child/children are being invited to be involved in this research study. Before you decide whether you want your child to take part, it is important for you to understand why the research is being done and what your participation will involve. Please take time to read the following information carefully to help you decide whether you wish to take part. If anything is unclear or if you would like more information please contact Mick Chesterman (email: m.chesterman@mmu.ac.uk)

What is the purpose of the study?

The project hopes to understand the process of making digital games. Two or more family members will join a larger group to explore creativity and problem solving in this context. The aim is that this understanding will help inform good practice for wider game making activities as part of family learning projects and venue programmes.

What will participation involve?

We would like to observe you and your child/children’s participation in an approximately 8-week (2 hours per week) game making programme. The activities are designed to support participants to review and make your own digital games that can be played on web browsers. Some of the work will involve using paper, pens, textiles, and other materials to make picture prototypes and generate sounds to include in the games created.

These sessions will occur during Autumn 2019 / 2020 at Manchester Metropolitan University (Brooks Building) during school time, facilitated by the researcher. You will be expected to accompany your child/children and participate in the activities.

There are no known risks, inconveniences or direct benefits, although we expect participants may increase their understanding of game making concepts and practices.

All written, drawn and material artefacts produced will be treated as research data. The researcher will make descriptive notes during sessions. Some activities will also be audio and video recorded. These recordings may be used for reflective interviews. These interviews will also be audio recorded, with the content analysed to inform reports or academic publications.

Approximately three weeks after the sessions are complete, each family unit will be invited to a follow-up interview.

Identities will be kept confidential through coding and the use of pseudonyms. Any images used in reports will be altered using Photoshop to create anonymised line art sketches. Video used in research presentations will be edited to maximise anonymity. All data will be stored on a password-protected external drive in a locked office at MMU.

Please note: - Names will be removed from all data, and information will be anonymised. - If there is any risk of indirect identification, we will consult with you. - You and your child can withdraw at any time by emailing Mick Chesterman. - If you withdraw, your data will not be analysed, and you may still take part in other activities.

Who to contact

For questions about the study: - Mick Chesterman, ESRI, MMU, Room 1.43, Birley Building - Email: m.chesterman@mmu.ac.uk - Phone: +44 161 124 72060

To raise a concern: - Prof Ricardo Nemirovsky, Faculty Ethics Committee - Email: r.nemirovsky@mmu.ac.uk

A3b. Information Sheet for Young Participants

Dear Student,

We are asking you to take part in a research project called Investigating the Potential of Family Game Making to Support Collaborative Production. We’re interested in how young people and their family members can work together to solve problems and create new ideas when making simple video games.

If you agree to join in, you and other students will come to Manchester Metropolitan University with your parent or guardian. You will use fun equipment and technology to explore and make digital games.

These activities will happen over about 8 days. Your parent or guardian will be with you the whole time and take you to and from the university.

We will video and record what happens while you work together and on the computer. When we show or write about the project, we’ll change your name and turn any pictures of you into cartoon-style line drawings, so no one knows it’s you.

If you change your mind, you can stop taking part at any time. Just tell us or let your parent or guardian know.

Questions? - Call: +44 161 124 72060 - Email: Mick Chesterman (m.chesterman@mmu.ac.uk)

A3c. Information Sheet for Practitioners

You are being invited to take part in a research study. Before you decide, it’s important you understand why the research is being done and what it will involve. If anything is unclear or you want more information, please contact Mick Chesterman (m.chesterman@mmu.ac.uk).

What is the purpose of the study?

he project explores how families make digital games together and how this process supports collaboration. The goal is to develop good practice for family learning and public programme delivery.

Why have you been chosen?

You have experience working with different age groups in digital game making. Your insights are valuable for the study.

This is a personal academic study. Whether or not you participate will have no bearing on your professional relationship with MMU.

What will participation involve?

You will take part in an interview about your experience, held at MMU or another convenient location. The interview will be audio recorded, and notes will be taken. These will be used to inform the researcher’s doctoral thesis and related academic work.

Participation is voluntary. You can withdraw at any time, and any data already collected will be destroyed and excluded from analysis.

Who to contact

For questions about the study: - Mick Chesterman, ESRI, MMU, Room 1.43, Birley Building - Email: m.chesterman@mmu.ac.uk - Phone: +44 161 124 72060

To raise a concern: - Prof Ricardo Nemirovsky, Faculty Ethics Committee - Email: r.nemirovsky@mmu.ac.uk

Appendix B: Methodology contributions

This appendix includes additional material that supported the methodological design described in Chapter 4. It provides examples of raw data excerpts, such as short transcript samples and the semi-structured interview guide used across phases. These extracts illustrate how the data collection instruments were shaped to reflect social, cultural, and material dimensions of activity, aligning with the CHAT–DBR framework used in the study.

B.1 Methodology - Extract of a transcription of activity divided into 5 minute segments

| Timespan | Content |

|---|---|

| 15:00.0 - 20:00.0 | Fok - Ed is looking for an animation frame already created Mark still reading documentation on how to add animation to a character. Mark: Quite complicated. But we can do it. But it would mean a lot of mucking around Ed: Ah Er Mark: Which is difficult to do while we’re here. But it’s doable. Mark: It’s like a project in itself really. Ed: Project in itself? Mark: Yeah! (laughing). I just want to know like. We can get him in. So if I ask about the sizing. Ed: Hmmn Mark: I think you can edit the size here. Ed: Why don’t you go here for a computer and you can do that? Mark: Why. What. While you’re doing what? Ed: Um making a sound track or something. I could do something like that. Mark: Ok. Yeah. I’ll see if there’s any more computers in the cupboard. Plan – Polish Child Solo – creating assets – |

| 20:00.0 - 25:00.0 | Ed then creates a head – struggling Seems a bit stuck – not able to recreate work Making noises to indicate stuckness after 10 mins Create – Polish Child Solo – creating assets – Pair – navigating to assets |

B.2 Methodology - Participants interview questions - semi structured

Introductory Questions

- In a nutshell, can you tell me about what you have done on the game making activities?

- What are some of the background factors that motivate you taking part in these activities?

- Is there anything that jumped out as successful

- Was anything unexpected?

Personal Dimensions

- What knowledge or skills are you trying to build by taking part?

- What about personal attributes / qualities

- Can you tell me more about any specific activities that did built knowledge or attributes?

- Tell me about any times you felt you could bring your own identities or interests into your making processes?

- Tell me more about how that happened and any impact it had on you.

- Tell me any times you felt you could choose your next steps or your own path of progression in your activities

- Tell me more about how that happened and any impact it had on you.

Material Dimensions

- Tell me about the software or hardware tools or materials you used

- How did they impact on how or how much you were able to collaborate?

- Did they make some of your goals easier or harder?

- What was your general thinking around these tools or materials, any other reactions?

- What about the resources used, printed or online? Similar questions to the above.

Social Dimensions

- What are your recollections of any social dimensions of learning you recall from the game making programme? Either Unstructured interaction or more structured, directed interaction

- Tell me about any specific activities or resources that you think may have supported this social approach to learning?

- What challenges do you think existed in this area?

- What are the pros and cons of working with families?

- What are the pros and cons of working with other families?

- Do you think the family nature of the programme impacted on how activities evolved?

- What observations about intergenerational interaction did you made?

- Are there particular any emerging patterns or roles of collaborative interaction that started to happen?

- Is there any other impact that the family learning environment have on the overall programme?

Cultural Dimensions

- Were you able to bring in interests of identities from family life to the programme

- Could you draw on any other activities or groups you are a part of?

- Did you make any links to any real life groups of people or communities outside the game making programme

- Are there tensions or challenges or advantages about concerning linking with outside communities?

- Are there other cultural factors which interacted with the game making programme?

Appendix C - Participant feedback, correspondence and detailed observations

Analytic location in the thesis: The materials in this appendix support analysis in Chapter 5, particularly Sections 5.5.2 and 5.5.3, where participants’ accounts of challenge, navigation, and engagement inform the identification of design contradictions within the game making activity. They also contribute contextual depth to analysis in Chapter 6 (Sections 6.4.2 and 6.4.3), where participant perspectives on collaboration, motivation, and belonging are considered in relation to the social and cultural use of gameplay design patterns. The correspondence and case study material provide supporting evidence for interpretations of participant experience, rather than serving as primary analytic data.

Appendix C.1 - Email to participants in mid-P1 - Never mind the bees. I need your help too!

Mick ChestermanM.Chesterman@mmu.ac.uk

Hi there,

Never mind the bees. I need your help too!

I really appreciate all your energy going into the game making club over the last weeks. This is an experimental process and you guys are really going for it.

Also special thanks to J* for doing the Sonic Pi session on Tuesday that was great, and I learned some useful things for doing that one in the future.

It was a bit of a hard session for me on Wednesday as I was a bit low on confidence about how to pull all of your creativity into a finished game! It started to feel like a bit of a fantasy!

So I think I realised something. I said in the past that the idea of the club is for you to follow your interests and I’ll do the job of pulling together that creativity into a game.

But I realised that I can’t do it alone!

So I think part of the work we have to do is to visually map somehow what we have now at the start of every session. Via prints outs, or sheets where we map what we have and what we are missing.

I’m happy to give it a go at the start of next session to try to explore one way of doing it.

But ideas via email would be very useful too.

And let’s also have a break out group at the end to work out a bit more of a team approach as I need your help!

Thanks loads for reading this far… Mick

ps: I guess the challenge is to do this so that it’s a map, with different learning directions and possibilities, but that we are all still on the same map in our groups.

So supporting autonomous learning but also team work.

Appendix C.2 – Case study with Anastasia’s family

One family in P1 chose not to continue with most other families after the Christmas break.

Members of this family had engaged in planning on paper and particularly in creating pixel art, however tensions began to emerge when the introduced code framework did not support the desired features of one child. The feature they wanted to add to the game was a bee design roaming a 3D landscape.

When the family withdrew, they shared in feedback (see below) that at one point the family looked around and just saw people doing “hardcore coding” and no longer felt that they belonged.

In the end stages of the game production process, due to the dynamics of the larger group, they had been reliant on others to implement code changes for their imagined game, were unable to contribute fully at this point, and found themselves isolated.

Thus, a contributing factor to this family’s alienation was tensions engendered by the large group size, compounded by frustrations stemming from unfamiliarity with tools and processes.

In participant feedback, the parent of this family, described in the previous section, indicated that too much time was spent in the planning stage and called for more hands-on play and use of the tools of production before being called on to make creative decisions. The parent likened this to an arts studio approach.

When the family withdrew, in my journal notes I reflected that their sense of alienation from the group process occurred in a session where, due to a sense of urgency to complete games, I had omitted drama-based warm-up activities. Instead, as participants entered, I began to support some families to debug pressing code errors.

For some families and individual participants there were conflicts related to anxiety and alienation from the group coding environment and associated peer working dynamics.

One family dropped out and in their exit interview they shared that at one point they looked around and just saw people doing “hardcore coding” and no longer felt at home in the environment. In this emergent design, they had mostly completed asset design and narrative development, and only coding remained. I therefore wanted to address the tension between completing the project and alienation arising from a focus on coding alone.

The value of playfulness is illustrated in one exit interview with a parent, where they shared their reasons for leaving the programme. At one stage, after a week in which they had missed a session, their family looked around and saw other groups involved in “hardcore coding” and no longer felt at home. They compared this with previous sessions, which had included more fun and group-oriented activity.

I was struck that this incident happened during a session where I had not played customary drama games to create an inclusive environment. These games had been omitted as I was responding to a sense of urgency from families to solve problems. The scarcity of facilitator time drove me to focus on supporting families to debug code errors.

Anastasia shared reflections on issues of family and home education dynamics, suggesting that parents may get in the way of young people’s ability to move into others’ spaces to learn, and that parental helping roles may therefore be a hindrance. The following is an excerpt from the end of P1 reflection notes, based on a short interview with Anastasia.

Process could have worked well if just kids.

Adults have more social rules.

Kids don’t mind copying, invading space.

But adults do. Some lack spontaneous approach.

If parents and kids work together, social rules are stuck to, in that the adults lead a learning process.

In feedback, the parent shared that she did not want to bother other families with problems via the email list, and also noted the hesitancy caused by parental involvement compared to children’s ability to jump in and learn from each other less self-consciously.

Thus, this surfaced a tension between the value of peer learning and the need for low pressure, in other words avoiding a negative sense of obligation.

Appendix D – Learning design appendix

Appendix D documents artefacts and reflections from the design-based research process, focusing on tools and activities created to support participant agency and collaboration. It includes explorations of maker types, side missions, and playtesting activities that developed over successive phases.

Analytic location in the thesis: The materials in this appendix support analysis in Chapter 5, particularly Sections 5.5.2 and 5.5.3, where design responses to emerging contradictions are described, and in Chapter 7 (Sections 7.2.3 and 7.3), where learning design artefacts are examined in relation to agency, participation, and the structuring of collaborative activity. These artefacts illustrate how design iterations translated theoretical insights into enacted pedagogical practice within the project.

Appendix D.1 – Maker types and social missions

The process of exploring identity within playful activities surfaced the cheekiness of some young people and the pleasure they took in demonstrating their playful mischievousness. I began to make journal notes on this subject and to talk to other game studies practitioners.

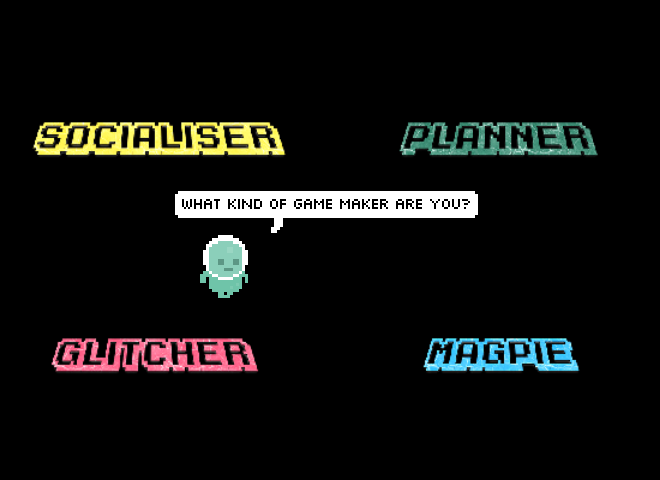

In discussion with then fellow PhD candidate John Lean, on his research on game playing styles (Bartle, 1996), I began to ask the question of whether surfacing maker types (as per player types) could encourage awareness of and celebrate the emerging practices that the community was producing. While this strand of activity is not key to the main thesis, it forms the genesis of later interventions, and as such a summary is included here, with a longer blog reflection available online1.

I translated the concept of player types to maker types based on notes in my observation journal. The following list outlines Game Maker types:

- Social makers: form relationships with other game makers and players by finding out more about their work and telling stories in their game

- Planners: like to study to gain a full understanding of the tools and what is possible before they build up their game step-by-step

- Magpie makers: like trying out lots of different things and are happy to borrow code, images, and sound from anywhere for quick results

- Glitchers: mess around with the code, trying to see if they can break it in interesting ways and cause a bit of havoc for other users

Participants, particularly older ones, used playtesting as a way of showing support for fellow game makers. Example behaviours included praising graphical content, making links with participants’ home interests through questioning, and building rapport. Madiha, in particular, used playtesting to show her appreciation of the graphical work of others, especially in the creation of cute animal characters. In response to one game which featured an image of a dog, other participants asked, Do you like dogs? Do you have a dog at home?.

It is worth stating that the reflections on game maker types or styles above are not imagined or proposed as exclusive or unchangeable styles. This statement addresses concerns around learning styles advanced by Fleming. The main problem with Fleming’s learning styles (VARK) is that there is little scientific evidence of improved outcomes or even of fixed styles in learners. Instead, the styles are advanced as a reflective tool and as a prompt for exploratory activities in the learning design.

Adapting the learning design to encourage activities exploring different maker types

My journal notes detail an evolution of attempts to build into the programme activities which help develop the participants’ sense of their own identities as game makers, or more generally as digital designers. By the end of P2, most of the tools and main processes were in place. However, I wanted to decrease reliance on my role as facilitator, to increase organic reflective processes, and to celebrate emerging participant identities. To do this, I began to integrate my observations of different game maker styles into the learning design more explicitly.

I used the question What kind of game maker are you? as an indicator to participants that one aim of the project was to create a space where different approaches are possible and celebrated. To communicate this approach, as well as to start game activity, I incorporated the question into an animation on the resources home page (see illustration below). In P3, the underlying ideas were incorporated into the process drama described in the next section.

Side missions

Full table of side missions

| Your Alien Mission (social) | Your Secret Alien Mission |

|---|---|

| Find out the names of 3 games that are being made. | Change the variables at the start of someone else’s game to make it play in a funny way. |

| Make a list of characters in two other games being made. | Change the images in someone else’s project to a totally different image and see if they notice. |

| Find out the favourite computer games of 4 people. | Change the level design of the first level of someone else’s project to make it impossible, but try to change as little as possible to do that. |

| Find out who plays the most computer games per week in your group. | Change the images in someone else’s project to a very similar but slightly different version and see if they notice. |

| Find out what other people are planning. Give some friendly feedback to one other person or group. Why don’t you try… | Add a rude sound to someone else’s project. |

| Ask 2 different groups if they have thought about what sounds they are going to put in their game. | Swap over some sounds in someone else’s project and see if they notice. |

| Find out from three groups if they are going to try any totally new ideas. | Delete all of the code of someone else as they are editing it and see how they react. Then help them get it back using the Rewind function. |

In the transcript of Vignette 4 we see that, in the end-of-session reporting back, participants engage in a lively discussion about the secret missions they had been given. Encouraged by her mother, Madiha, Nasrin shares that she has been highly engaged in a disruptive secret mission. Dan and Toby express playful frustration. Mark and Ed contribute by sharing their more subtle disruption, and Richie is keen to have his rude noise mission noticed and commented on. Some public missions had a noticeable impact in this session, particularly in stimulating a discussion among parents around which arcade games they played as youths.

Side missions or side quests are also used in open world games to appeal to different kinds of players, and are often modelled on Bartle’s taxonomy of game player types (Bartle, 1996). In this phase, parents Madiha and Mark both used the prompts of the social missions to take a break from their creative work using the software toolset, to talk to other parents and children.

Mark: Right we’ve got a background in. Do you. Do you want to reply to the Weean.

Ed: Yes. (Ed starts to type very slowly)

Mark: (after some time) While you do that I’m going to go do my mission.

Ed: What’s your mission?

Mark: To find out about other people’s favourite games.

Ed: Alright.

In later reflections, parent Mark made the following comment in post-session interviews: “We used the instructions, we like to plod.”

D.2 – Playful playtesting

The maker types listed above were particularly played out in the playtesting process. Some children added additional playful elements to playtesting. Because these interactions were mobile between workstations, it was hard to extract audio and transcribe their speech. However, it is possible to communicate the characteristics of this play via a description of a typical encounter and the gestures of participants.

Play is initiated by calling across the room as an invitation to play, or as a provocation. When playtesting is underway it is normally undertaken with two or three participants standing around the computer rather than being seated. The core of those involved take turns to play the game, exclaiming frustration or triumph at completing levels or failing. Failure may be extremely performative, with a rapid pulling away from the screen and keyboard. This may be followed by a battle to wrestle control of the keyboard to play the game next. This may involve playful pushing and wrestling of hands and arms, and vocalisations. While this play is happening it may attract other participants, who remain on the outskirts of the activity, able to watch what is happening on the screen and respond non-verbally with smiles or laughs.

These changes to the form and function of playtesting by young participants are another example of the expression of agency by participants that widens the scope of possible actions.

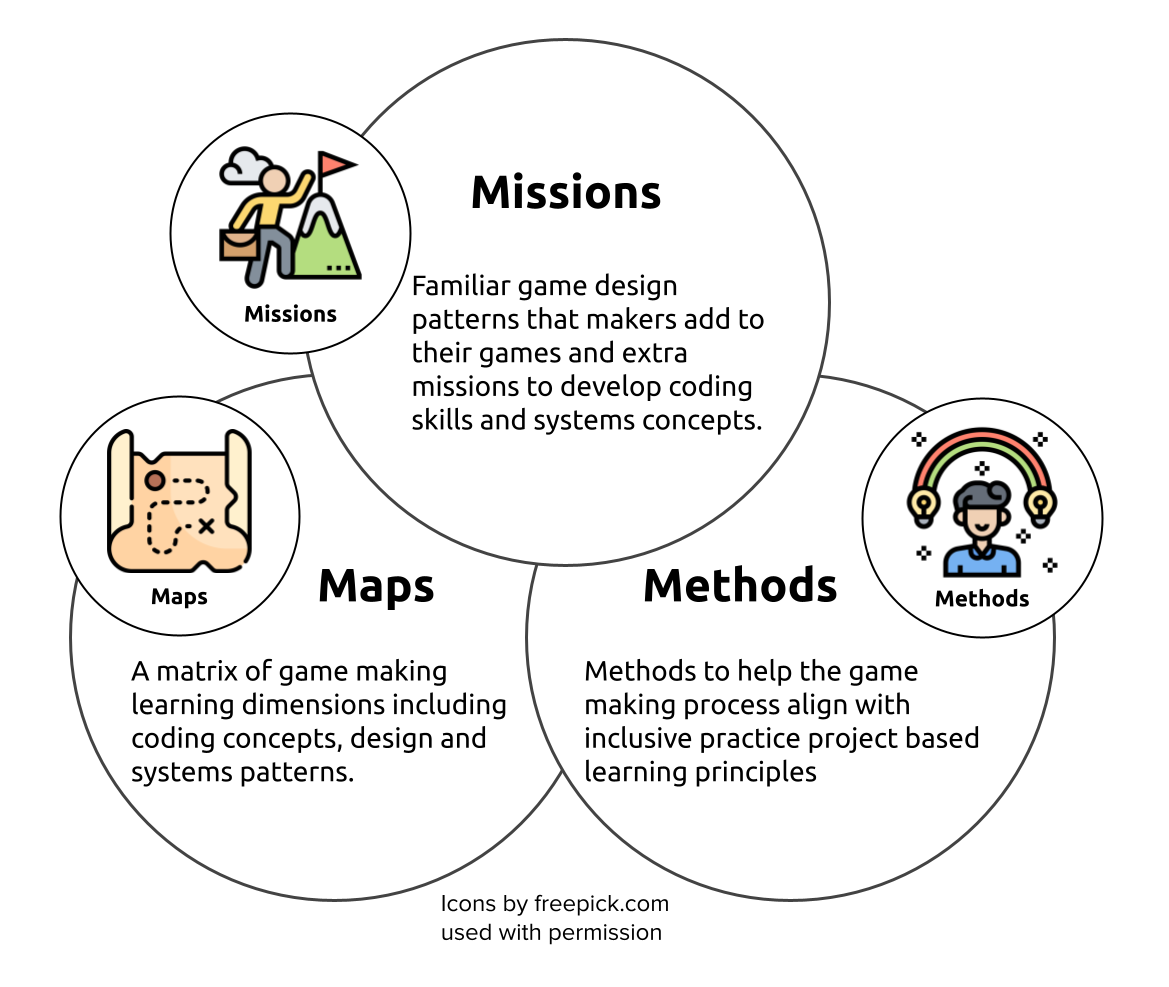

Appendix D.3 – A breakdown of the 3M Model

| Missions | Maps | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Simple code changes yield quick feedback | A map of learning dimensions flexibly linked to main missions and patterns can be used by both learners and facilitators | Playtesting in each session aids short-term motivation. Showcase events help longer-term motivation and aid project prioritisation |

| Free choice of patterns increases learner engagement and ownership | Tracing the learner pathway on an attractive physical map in the learning space can help integrate navigation and reflection into the creative process | Drama and fictional scenarios can help explore issues and reduce learner anxiety through coding in a role |

| Restrict game type and number of patterns to reduce facilitator stress | Adding electronics to control the game via arcade buttons and cabinets increases engagement and perceptions of project authenticity | |

| Limit complexity of patterns. Some are simple but cause a large change in the game | ||

| Side missions which explore and celebrate different approaches to making (based on Bartle’s player types (Schneider, Moriya and Néto, 2016)) |

Table 5.5 – Key features of the 3M Game Making Model

Appendix E – Technical appendices

Appendix E lists the accompanying technical resources that extend this thesis into an open documentation format. These online materials include the facilitator’s toolkit, detailed design narratives, template analyses, and workflow documentation used in writing and data handling. They serve as an open-source reference for practitioners seeking to replicate or adapt the project’s methods and tools.

Analytic location in the thesis: The technical appendices support the practice-oriented analysis developed in Chapters 5 and 6 by providing open documentation and artefacts that extend discussion of learning design, tooling, and facilitation into actionable resources. The materials also underpin aspects of the methodological approach discussed in Chapter 4, particularly in relation to documentation practices and workflow transparency.

- 00 – Facilitator’s Toolkit: A summary of the different resources created as part of the research process, structured to be replicable by other practitioners.2

- 01 – Additional design narrative of tool evolution: An extended design narrative documenting the evolution of tools and resources used during the study.3

- 02 – Technical analysis of the game template design of the study: A detailed examination of the structure and evolution of the game templates used within the project.4

- 03 – On technical and digital literacy skills: Reflections and analyses relating to technical and digital literacy practices that emerged through participation.5

- 04 – Thesis writing workflow: Documentation of the workflow, tooling, and organisational practices used in the writing and production of this thesis.6

References

Bartle, R. (1996) ‘Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit MUDs’, Journal of MUD research, 1(1), pp. 19–26.

Schneider, M.O., Moriya, É.T.U. and Néto, J.C. (2016) ‘Analysis of player profiles in electronic games applying Bartle’s taxonomy’, São Paulo [Preprint].

-

https://micksphd.flossmanuals.net/tech_appendix/00_facilitator_toolkit/ ↩︎

-

https://micksphd.flossmanuals.net/tech_appendix/01_design_narrative_extra/ ↩︎

-

https://micksphd.flossmanuals.net/tech_appendix/02_template/ ↩︎

-

https://micksphd.flossmanuals.net/tech_appendix/03_digital_skills/ ↩︎

-

https://micksphd.flossmanuals.net/tech_appendix/04_thesis_workflow/ ↩︎