07. Pumping up the Jam

Findings: Pumping up the Jam - structuring participation and agency in game making

Introduction

The analysis across the past two chapters has moved from the design process (Chapter 5), through the role of gameplay design patterns as mediational tools (Chapter 6), to the present focus on agency. Chapter 5 showed how tensions in the learning environment prompted design responses. Chapter 6 examined how GDPs supported participation and seeded cultural practices. Chapter 7 now brings these strands together to explore how these resources and practices translated into different forms of agency, shaping how participants coordinated intentions, roles, and cultural repertoires within the community.

This chapter builds directly on the preceding analysis of gameplay design patterns as mediational tools. Where Chapter 6 traced how GDPs structured participation, supported fluency, and seeded idiocultural practices, here the focus shifts to how those same practices translated into agency, specifically how they enabled participants to take initiative, reframe goals, and coordinate roles in ways that reshaped the object of activity.

The analysis develops two linked strands reflected in the first two parts of this chapter. First, it considers the abstract and concrete dimensions of computing education, continuing the discussion opened in Chapter 6 but deepening the discussion on tensions related to structuring participants’ experiences whilst striving to increase their autonomy within the learning experience. This involves examining how learners moved between immediate, hands-on activity (such as debugging or remixing code) and more abstract conceptual framings, and how GDPs provided a relatable navigational framework for those transitions. In highlighting these shifts, this strand demonstrates how participants began to claim greater authorship over their learning rather than following pre-structured pathways. This part also advances a pedagogical framework named REEPPP which synthesises diverse threads of structural support that evolved in the learning design of this research.

Second, the analysis of this chapter situates the actions of participants within cultural and interpersonal contexts, examining how idiocultural practices, peer collaboration, and family involvement served as resources for agency. This strand emphasises how shared repertoires were mobilised to coordinate learning across individuals and groups. In doing so, the chapter traces three interrelated forms of agency: instrumental agency, visible in participants’ ability to use tools and patterns to solve immediate problems; transformative agency, where learners reframed goals and shifted the direction of activity; and relational agency, expressed in the coordination of roles, repertoires, and cultural resources across the community. In this part I develop an interpretation of relational agency drawing on Rogoff and Gutiérrez’s (Gutiérrez and Rogoff, 2003) concept of learner repertoires. To do this, the findings of this research are framed within a novel model, relational agency by repertoire blending (RARB), describing three stages of a process of agency development.

A final section summarises findings for a broad audience, addressing the characteristics of the design that support relational agency, presenting a graphical representation of the development of agency, and exploring a metaphor that synthesises significant features of the learning design by aligning this process with musical improvisation.

Part One - Exploring concepts of abstract and concrete knowledge frameworks in relation to game design patterns

The tension between the abstract and concrete dimensions of the process of learning to program runs as a theme through existing research on computer game design and programming (CGD&P). Yet, the field would still benefit from research on novel pedagogies that explicitly address the complexities of abstraction within computing education (see Chapter 2). Areas of complexity relevant to this study include: issues of degrees of abstraction in understandings of computational thinking (Wing, 2006; Brennan and Resnick, 2012); the potential benefit of understanding the role of levels of abstraction for teachers and learners (Waite et al., 2018); and epistemological pluralism as a way to value concrete approaches (Papert and Turkle, 1990). In what follows, this section first revisits these debates, connecting them to data from Chapters 5 and 6, and finally develops a contribution that positions gameplay design patterns (GDPs) as a construct located between the abstract and concrete poles of the learning experience. This positioning is used to examine the utility of GDPs for facilitators and participants. I then advance a technical pedagogical structure, termed remix-enabled elective pattern patching (REEPPP).

Conceptions of abstraction in the research field

This section begins by exploring dimensions of abstraction and concreteness in the use of GDPs within the context of computing education by revisiting relevant pedagogies outlined in Chapter 2. In this study, GDPs are conceptualised as both intermediate-level learning design principles (explored in Chapter 5) and as units of analysis (see Chapter 3), as well as analytical germ cells manifested in varied motivational and mediational forms (as discussed in Chapter 6). The research process, informed by CHAT-based formative interventions, involved identifying GDPs from empirical data as abstractions of analytical and practical value, and then using these abstractions to generate distinct concrete instantiations within the evolving design. This repeated movement from observation to broader application reflects a process CHAT describes as rising to the concrete.

Exploring findings in relation to existing pedagogies

Computational thinking and bricolage

While computational thinking is not a pedagogy, it has formed the basis of a significant amount of research on diverse pedagogies to support its development. As such, a summary in relation to the findings of this research is relevant here. Chapter 2 explored definitions of computational thinking that vary in degrees of abstraction or application. Two notable interpretations include Wing’s (2006) focus on abstraction encompassing overarching computing principles and high-level structural design approaches, and Resnick and Brennan’s (2012) more applied approach, including computational practices and perspectives. The applied approach of Resnick and Brennan draws on the legacy of Papert and Turkle’s (1990) research on diversity in coding approaches to counter potentially alienating abstract approaches that are dominant in programming education. By way of contrast, bricolage approaches maintain strong links between function and form. The findings of this thesis suggest that participants’ practices within the context of this research resembled bricolage, a theme explored further in the following sections.

Exploring findings using concepts of semantic profiles and LOA

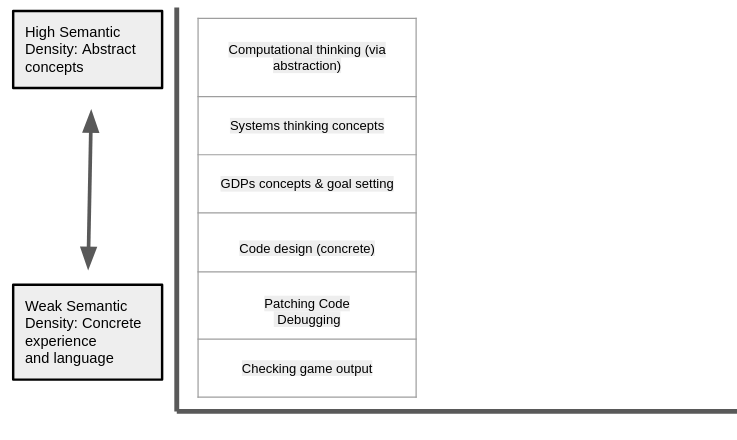

Levels of abstraction (LOA) and semantic profiles were explored in the pedagogical discussion in Chapter 2 (Waite et al., 2016; Sentance, Waite and Kallia, 2019). A shared feature of both models is the recommendation that learners shift their focus between abstract and concrete levels of project structure and semantic concepts, respectively. The pedagogies are advanced to help teachers design learning experiences that allow participant shifts in perspective and thus deepen knowledge by packing and unpacking abstracted concepts via concrete experiences, in line with legitimation code theory (Maton, 2013). In this thesis, there are two principal dimensions of abstraction at play. The first follows Wing’s definition of computational thinking (centred around decontextualised concepts of abstraction, generalisation, and decomposition) at one pole and concrete code implementation at the other. The second dimension of abstraction is represented in the LOA framework as a hierarchy of elements, namely: goal, design, code, and results. To better explain how I interpret each tier of the model in relation to my findings, Table 7.1 contains a contextualised summary.

| Level (from LOA model) | Adapted level description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Level | GDP concepts and goal setting. | Choosing what features to add to the game in the form of GDPs. |

| Design Level | Code design (concrete). | Design choices involving coding concepts and knowledge of the structural organisation of the code project. |

| Code Level | Patching code, debugging | Adding, checking, and debugging the lines of code. Supported by the code template structure. |

| Execution Level | Checking game output | Understanding the outputs. Acting on feedback to test the correlation between goal and outcome, often via the self-playing of the game being worked on. |

Table 7.1 - Description of levels of abstraction located in the findings adapted from Waite et al. (2018) (see Table 2.1)

Returning to semantic profiles, Curzon et al. (2020) advocate the mapping of the student experience of abstract and concrete concepts that students encounter during the timescale of a lesson as a way to help teachers conceptualise and facilitate computing programming. However, while promising for the interpretation of the data of this research, the authors do not propose concrete typologies to guide this mapping. To address this, I have created an applied typology (see Figure 7.1 below), which incorporates the concepts of abstraction explored in Chapter 2 through the lens of the findings of Chapter 5 and 6. I was guided in this process by the work of Höök and Löwgren (2012) (see Section 2.5), which places gameplay design patterns centrally, below abstract concepts and above those involving more concrete implementation. I also judged it appropriate to place the tiers represented in the LOA model in the lower half of the profile (see Figure 7.1), and additional abstract levels of computational thinking and systems thinking in the upper section.

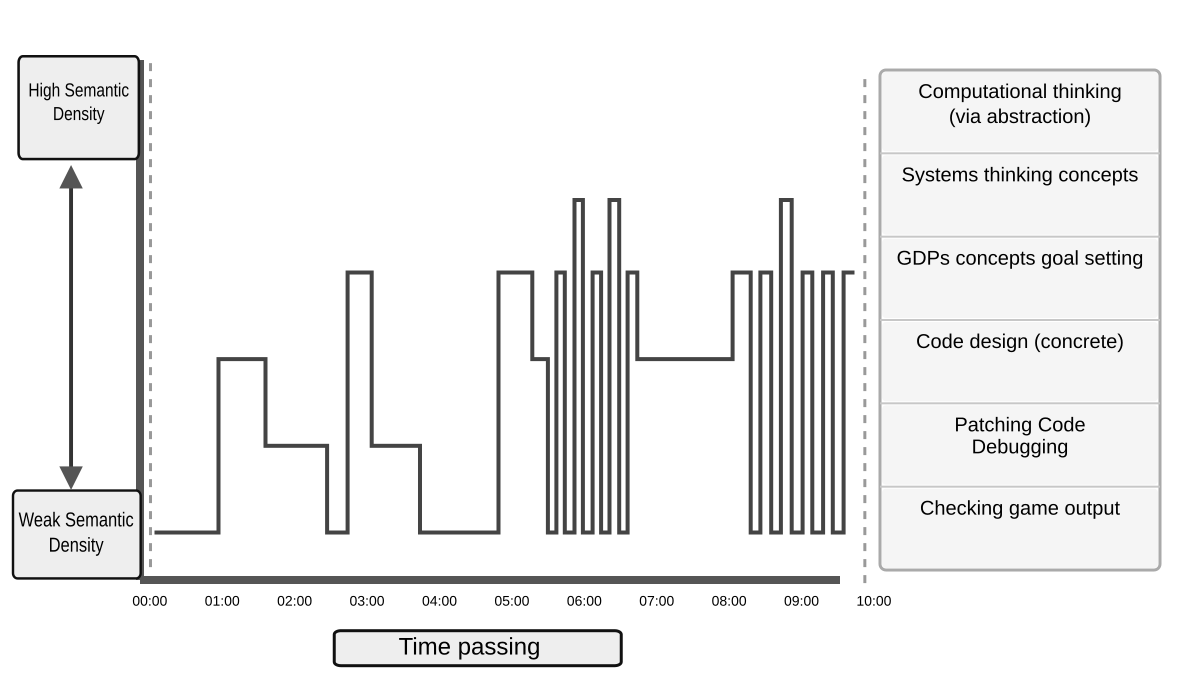

To illustrate this enhanced interpretation of LOA (Waite et al., 2018) in context further, using video data from Vignette 1 (see Chapter 5 and 6), I have mapped the levels of abstraction to shifts between conceptions of goals (as GDPs), code implementation structures, and observations of results undertaken by Toby (child). The representation of these shifts shown in Figure 7.2 draws on a close time-coded analysis of the first 10 minutes of Vignette 1, which is also available as a descriptive table in Appendix V.

Movement between layers of abstraction and concreteness occurs as Toby shifts between goal formation and concrete implementation using design practices and specific code structures. Toby starts by imagining and choosing a design pattern and navigates to the relevant documentation. He progresses to implement the pattern via patching in code from the code example. He tests it via previewing and playtesting the game. He then revises or debugs it iteratively. For example, he is required to make several changes to get the positioning of the moving enemy correct. In doing so, his activity oscillates between checking game output (execution level) and debugging (code level). Examples pervade the video data of similar iterative shifts between these lower levels. Increasing participant fluency via operationalisation (see Chapter 6) is interrelated with this repeated movement between levels and perspectives. The data indicates that games provided significant motivation to adjust code to get the resulting game balance feeling just right. GDPs provide a framework and shared language to help guide and articulate this process to other designers. There is a strong link between the concept of GDPs and the tangible experience of them within feedback during the process of playing the resulting game (as explored in Chapter 5 and 6). This data shows that this use of GDPs contributes to clearer pathways for participants in navigating levels of abstraction at play within the CGD&P process, a goal cited within existing research on LOA (Waite et al., 2018).

While the semantic profile shown above and those within data in other vignettes show rapid and repeated shifts in participant perspective, they contain comparatively little activity at the code design level or use of more abstract computing concepts. Figure 7.2 shows that, in this extract, exploration of abstract computational thinking concepts is present only very infrequently. Instead, the semantic profile shows movement in the lower areas of the gradation of semantic density. This shallow semantic wave above is broadly representative of the data, not only of Toby’s activity but also that of other participants in analysed session recordings. This pattern is due in part to the fact that I had pre-completed aspects of project implementation that required more generalisable computational thinking skills. For example, abstraction was present in my structuring of key variables within the starting template and via the graphical design tool in the form of a grid matrix in an array data structure. Decomposition and generalisation (pattern recognition) were present in the structure of the collection of GDPs based on the MDA (Mechanics, Dynamics and Aesthetics) framework. For advocates of the potential of abstract interpretations of computational thinking, this organisation could be perceived as over-scaffolding, depriving learners of the chance to learn and practise valuable computational thinking principles (Pea, 1987; Curzon et al., 2014).

These scaffolding decisions were initially made to address barriers associated with abstract approaches and conceptual complexity, thus prioritising accessibility and flow experience for participants (see Chapters 5 and 6). As such, the resulting semantic profile of Figure 7.2 above can be aligned with the description of Papert and Turkle’s (1990) bricoleur maker styles and constructionist design heuristics (Resnick and Silverman, 2005) (see Section 5.4). Observations show most participants operating as bricoleurs, feeling their way through smaller-scale design iterations rather than extensive planning followed by implementation. The process of scaffolding the design in this way, and thus abstracting away complexity (referred to as black-boxing by constructionist researchers (Resnick et al., 2005)), allowed greater focus on the relational and affective elements of the learning design, processes that are described in more depth in part two of this chapter.

The findings of this chapter support a position that the process of mapping participant experience of learning experiences to LOA dimensions is a productive process to review their inherent accessibility (Waite et al., 2018). However, the value of participants being explicitly aware of LOA is less explored in these findings. While systems concepts and computational thinking concepts are being engaged with by participants at the concrete level, and were included in written instructions, such concepts were not explicitly taught in sessions in a generalisable fashion, an intentional decision taken to prioritise engagement. These intentional limits to the exploration of more abstract concepts, in line with a bricolage approach, appear to be at odds with advocacy for alternating between abstract and concrete dimensions in semantic waves (Curzon et al., 2020). It follows that Curzon and colleagues may consider this to be a problematic limitation in the bricolage-aligned approach described in this chapter, or at least as a missed opportunity to unpack and repack concepts (Maton, 2013).

While the value of explicit teaching of more abstract dimensions of computational thinking is not challenged here, my findings expose potential tensions in doing so. At times, when my time was less pressured and participants appeared to me to be receptive, I would explain CT concepts in relation to the code structure they were working on1. In Vignette 1, a suitable occasion to do this would be when Toby made changes to the graphical level design grid construct, where a facilitator could draw attention to the technical aspects of that coding construct (in this case, the structure of data arrays). Within my choice concerning the use of responsive, direct instruction of abstract concepts while code was being worked on by participants, I balanced factors such as how useful such information would be for them in future problem solving with the potential unwelcome interruption of their flow. A tension involving competing demands on the facilitator is also relevant, as there was a high demand on my time and I prioritised working with participants to solve concrete coding issues when they were stuck, to keep them engaged, rather than explaining the underlying computational thinking or systems concepts. While there were instances within the recorded data where I took time to explain more abstract concepts, because of the factors listed above, these were scarce. Given a different focus or motivation, for example a need to explore concepts due to curricular or exam-related factors, the process of supporting students to explore more abstract concepts could have been scaffolded further through more explicitly guided reflective processes. The map of learning dimensions created as part of this research (see Chapter 6) could assist practitioners and participants to chart and thus facilitate exploration of relevant coding and systems concepts. This potential is developed in the concluding chapter.

Interpreting GDPs as both intermediate-level knowledge and as a gateway pedagogical concept

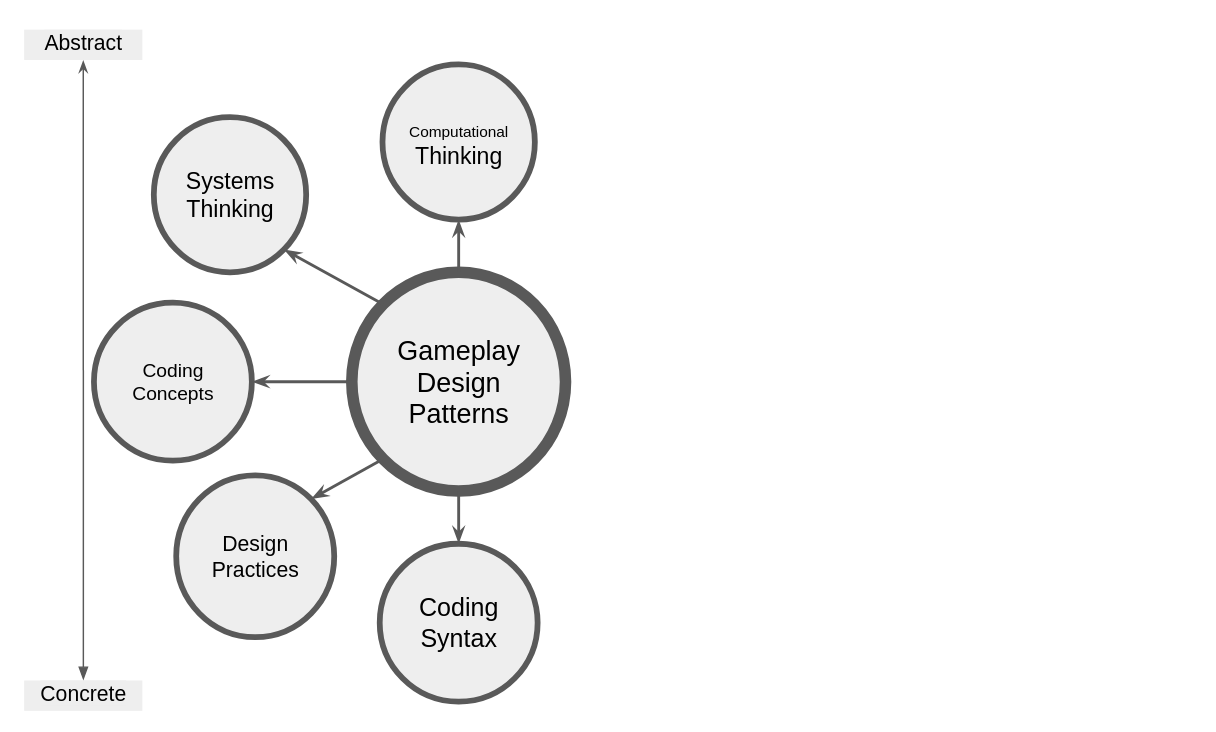

While this research has avoided focusing on the explicit teaching of concepts, it has, as described in the section above, surfaced a mechanism for using GDPs that allows more accessible access to both abstract and concrete elements present in the learning environment. Eriksson et al. (2019, p. 15) frame design patterns as a form of “intermediate-level knowledge” between the detail of concrete implementation and more general theories (Höök and Löwgren, 2012). In addition to this interpretation, I propose that GDPs act as gateway concepts that offer pedagogical utility for accessing different layers of learning experiences. The use of GDP concepts as a primary object of activity affords, through their intermediary positioning, an exploration of both abstract and concrete concepts. This is represented conceptually in Figure 7.3 below.

The framing of design patterns as an intermediate construct in initial work by design researchers (Höök and Löwgren, 2012; Barendregt et al., 2017; Eriksson et al., 2019) was primarily used as a tool for researchers to surface design concepts to act as a lingua franca to deepen analysis. While this use remains valid in this research, the example above (GDPs as a gateway concept) shows one instance of how this framing has been used in this thesis for purposes beyond academic interpretation. As explored in Chapter 5, for facilitators GDPs can serve additional functions within inclusive pedagogical approaches, including the ability to structure participant choice within practical limitations, and acting as a unifying construct to aid the packaging of documentation and the support provided to assist project navigation. In addition, the experience of participants in the last chapter outlined their varied uses of GDPs in terms of mediational strategies and as a motivational element, repeated in varied forms as different GDPs are implemented. The findings of this chapter indicate that these uses of GDPs by varied actors share a dialectical movement between abstract and concrete poles. Using foundational CHAT interpretation, GDPs act as a germ cell concept within a process of rising to the concrete, in the varied forms illustrated above.

Summary of the structural components of an applied pedagogy named REEPPP

The previous section has shown how, instead of explicit teaching of concepts, the structural support provided by the use of GDPs allowed flexible navigation of abstract and concrete elements of the learning experience, driven chiefly by participant choice. This section summarises an approach to facilitate the use of GDPs via a technical structuring of resources and practices. To communicate the essence of this structural, technical model, I propose an acronym: remix-enabled, elective, progressive, pattern patching (REEPPP). The key elements of this pedagogy constitute a replicable approach, which is a valuable contribution to both coding education and wider domains. As such, the summary table outlining the features of the REEPPP approach has been written to be applicable to projects beyond game making alone, potentially extending to wider digital media making. Brief examples related to this research are included at times to increase clarity.

| REEPPP Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Remix Enabled | Project formation is accelerated, limited, and scaffolded through the use of a structural starting template in a recognisable project genre with easily discoverable affordances, strongly coupled with object output, providing immediate feedback (e.g. changes to game code are instantly available for review via playtesting). |

| Elective | Participants have choices over their learning pathways in dimensions of content and design patterns to be added. |

| Progressive | The process involves progressive steps in templates used and activities carried out. For example, game pattern recognition through exploration and play, quick-start activities involving minimal changes with high impact on the project outcomes, using progressively more challenging documented patterns, and finally implementing patterns without support. |

| Pattern | The process has at its core the use of recognisable design patterns, which are presented together with suggested design solutions (e.g. the menu of GDPs with associated tutorials and concrete code snippets). |

| Patching | The authentic technical process of code patching accelerates production and creates errors suitable for problem solving and revisions (e.g. code debugging) at a novice level. |

Table 7.2 - REEPPP as a technical structure that synthesises key elements of the learning design

This technical structure synthesises the use of a code playground, a game library, a half-baked game template, UMC pedagogy, and a collection of game design patterns (see Chapters 2 and 5). While similar approaches exist, this structural pedagogy is innovative in the way systemic tensions have been resolved and congruencies introduced (see Chapter 5). These tensions were worked through by matching open-ended remixing with a simple sequence of pattern-based steps. This gave participants freedom to explore while still having a clear path to follow. The approach brought together tools and teaching strategies so that the technical resources and the pedagogy supported each other, rather than pulling in different directions.

The first part of this chapter has, through an analysis of the characteristics of the learning design related to abstract and concrete elements of computing knowledge, addressed a gap in research in identifying an appropriate level of scaffolding (Quintana et al., 2004; Waite and Sentance, 2021) to support CGD&P, as identified in the problem statement of this thesis. The use of conceptual and practical frameworks to scaffold domain-specific working practices can help ameliorate the dialectical tension between engagement via tinkering and the requirement to promote “principled understanding” (Barron et al., 1998, p. 63). In addition, the findings of Chapter 5 have been reframed to communicate the value of a structural approach I call the REEPPP approach, which hinges on the use of design patterns to access and facilitate varied dimensions of a project-based approach to media making. While this chapter has so far focused on the personal dimension of knowledge, the scaffolding provided by the REEPPP approach accelerates and supports the making process, which in turn allows for greater possibilities for agency within the social and cultural dimensions of the game making activity. These themes are explored in part two of this chapter.

Part Two - Agency, and remediation of repertoires in third spaces

Building on the scaffolding outlined in part one, a key motivation of this study is to better understand how to mobilise potentially fruitful socio-cultural perspectives via replicable pedagogical strategies to facilitate participant agency during CGD&P. Part two of this chapter is guided by Papert’s foundational orientation towards community aspects of programming project work (Lodi and Martini, 2021) and his related articulation of computational fluency (including expressive dimensions of the making process) as an alternative focus to that of research addressing abstract conceptions of technical coding proficiency (Resnick, 2020; Resnick and Rusk, 2020). This section is structured in the following way. Firstly, given that a guiding motivation of this study is to gain an understanding of participant empowerment within CGD&P, an exploration of evolving expressions of agency shown in the findings is undertaken using the concepts of instrumental, transformational, and relational agency (Matusov, von Duyke and Kayumova, 2016; Hopwood, 2022). Following this is an ecological analysis of the cultural plane of activity emerging from the findings of this research. To do this, I draw on socio-cultural understandings of agency development as a utopian process (Gutiérrez, Jurow and Vakil, 2020; Rajala, Cole and Esteban-Guitart, 2023), using concepts of third spaces, movement of participant repertoires, and the evolving hybridity of repertoires.

Transformations in agency

Chapter 2 examined the concepts of flow and varied characteristics of fluency in constructionist research. Chapter 6 explored these concepts in relation to the data of this study and proposed the related concept of agency as being more closely aligned with a socio-cultural approach. Many of the decisions outlined in Chapter 5 (see Table 5.5 summarising tensions involved in the learning design) can be interpreted as increasing agency in practical terms by developing elements within the design that act as mediational affordances2 or that help reduce barriers to undertaking programming. Conceptually, these practical dimensions can be framed as addressing instrumental agency, as they remove aspects of “negative liberty” caused by technical barriers (Matusov, von Duyke and Kayumova, 2016, p. 433). Instrumental agency in education can be viewed as a relatively uncomplicated view of mediation to achieve pre-set goals (Matusov, von Duyke and Kayumova, 2016). A distinction can be made between instrumental agency and transformative agency (Isaac, Barma and Romero, 2022), in which expressions of instrumental agency are unlikely to provoke environmental changes in the activity system at hand. Transformative agency, by way of contrast, may stem from individual motivation but also involves a transformation of systemic constraints (Hopwood, 2022). Sannino (2015a, 2022), presenting the concept of transformative agency by double stimulation (TADS - see Chapter 3), highlights that participants’ agentic acts of volition that aim to overcome conflicts blocking activity progress may serve to create new (or surface previously unused) forms of mediation and tool use. The emergence of the pedagogy used in Phase 2 of activity was informed by my observation of participant acts of volition. In early stages, as a facilitator, I made available a variety of activities and materials to facilitate the potential for double stimulation (see Chapter 5.3 for a summary of how observations of participant behaviour shaped a subsequent reduction of the toolset used). After noticing that volitional attempts by participants were reaching for more structured supporting resources, I produced relevant resources and increased their visibility within the pedagogical design. This process raises a question: does adapting designs to increase instrumental agency reduce opportunities for transformational agency in future iterations? In other words, once prototypical resources and scaffolds introduced experimentally to encourage TADS are adopted and refined does the form of agency in play shift from transformative to instrumental agency. If so, this raises an additional question. Would it be advantageous to keep some key areas of the learning design incomplete to encourage the emergence of participant responses and novel practices, thus retaining the potential for transformational agency?

This line of thinking raises challenges for facilitators: how to balance the transformative potential of incomplete learning environments with the potential for participant frustration associated with learning programming3. In this research, tensions associated with frustration were ameliorated via the use of play and other processes to create an inclusive, low-stress environment. These strategies were beneficial in enabling participants to feel able to experiment with new forms of mediational strategies and thus enact transformational agency. Another relevant concern is how to support the incorporation and propagation of strategies that emerge from individual TADS processes into the game making community (see Chapter 6.4). This concern is explored through the concept of relational agency in the following section.

Turning to relational agency in the learning design, the complex relations between participants are outlined in the vignettes and data of Chapter 6. These relations, particularly evident in the sections addressing guided participation and cultural activity, can be characterised as interdependence, one of the key features of relational agency (Edwards, 2005). Edwards (2009) explores relational agency within a CHAT framework, describing it as transcending individuals’ capacity to encompass collective problem-solving via specialisation and diversity of approaches within activity systems. As a collective, participants can overcome systemic contradictions via expansive learning, rearranging working relationships, and thus forging new, mutual forms of helping and learning strategies. In subsequent writing in this chapter, the concepts of instrumental and transformational agency are understood to be incorporated within this wider definition of relational agency.

Socio-cultural perspectives on agency and repertoires

The discussion section of Chapter 6 examined the complexity of the object of activity in this research from a CHAT perspective4. It highlighted both the diversity in terms of motivations and mediational strategies present, and acknowledged the limitations of 3GAT in clearly representing the important interactions between activity systems (Engeström, 1996). To address these limitations, this section draws on techniques used within social design-based experiments (SDBE), reframing the findings of this thesis using the concepts of repertoires and third space, with attention to issues of participant identity, agency, and the movement of practices between learning settings (Gutiérrez and Jurow, 2016). For Gutiérrez (2008), third spaces are collective zones of proximal development, which can be both a specific environment and/or a process within existing contexts supporting a hybrid approach where diverse repertoires are re-mediated or blended in collaborative work on an expanded object. To augment this interpretation, Rogoff and Gutiérrez (2003; 2019) advanced the concept of repertoires as a lens to contribute to the discussion of expansive learning in CHAT as a positive, enacted demonstration of diversity and equity (see Section 3.3). The overall goal of the following section is to explore the appropriation of diverse, existing participant repertoires (Gutiérrez, Baquedano‐López and Tejeda, 1999) into the third space of the game making community and to explore the development of new mediational tactics and other repertoires.

Importing repertoires into the community

Drawing on Gutiérrez’s (2008; 2019) concept of learning as movement between spaces, participant repertoires can be understood as being imported from other activity systems into the emerging third space of the game making activity. These repertoires acted as the raw material for later blending. Their mobilisation marked the first step in a longer process of agency development, as participants brought their home-based knowledge into the shared activity. This section triangulates observational video data and post-session interviews to locate certain repertoires as pre-existing rather than newly formed within the game making context. Two key strands of imported repertoires are identified: those derived from divisions of labour and those involving funds of knowledge.

Addressing first repertoires involving divisions of labour, this research supports existing research on potential helping roles in technology use identified by Barron and colleagues (2009) (teacher, project collaborator, learning broker, non-technical consultant, and learner), which are present in my data from the initial stages. These roles were played out in observed practice or in interview data, as shown in vignette data. In video data and interview data with Susanna (parent) and Tehillah (child), the parent details how she is able to support her child based on her home knowledge of working styles, and specifically the use of paper to help the child sketch (see Vignette 2). The use of paper and pencil for prototyping is also described by Mark (parent) and Ed (child), who describe it as a home practice imported to this space (see Vignette 3). Mark (parent) describes a style of working slowly and methodically as plodding, a term he used to describe their systematic progression through the step-by-step online documentation provided for each GDP as part of the game making sessions. My involvement also impacted the emerging division of labour of the activity. The recruitment process for the game making programme of this research set an expectation for parents to get involved with the game coding as well as young people. Maggie, the parent of Toby, shared her thoughts on the changing nature of home education communities, noting that parents are now more passive and think of their roles as arranging tutoring for their children, whereas the adults in her family are also keen to be involved in their children’s learning activities where possible.

Other divisions of labour, which highlight imported repertoires and roles of young people, are present in the data. Madiha (parent) describes Nasrin (child)’s strong preference for independent working, which Madiha respects and accommodates (see Vignette 4). Anastasia (parent) also shared reflections on the issues of family and home education dynamics, suggesting that parents may get in the way of young people’s ability to interact with other children to access peer learning experiences, and that close parental help may therefore be a hindrance at times (see Appendix C.2).

Turning to funds of knowledge and interest evidenced within this research data, these include the areas of game playing interests, art, environmental and other global concerns, and professional knowledge (see Section 6.4). Some adults imported knowledge from professional communities or previous studies. Maggie had studied the coding language Pascal, and Dan brought practices from his work and from volunteering at a monthly family coding club (see Vignette 6). Movement of repertoires into the learning space was also well illustrated in the use of game-related knowledge. For example, the use of a half-baked game as a starting point allowed non-programming funds of knowledge to be mobilised in several ways. Participants’ knowledge concerning the norms of the platform game genre helped with initial orientation and ongoing participation through their motivation to alter and personalise the game. In interview data, Nasrin (child) shares some of the links between her home game playing practices (in particular Minecraft) and the graphical asset authoring undertaken in these game making sessions. This surfacing of home interests into a shared and visible process had an additional benefit for some parents. Madiha (parent) shared that via joint game making she had developed greater understanding of, and had become more involved in, Nasrin’s home gaming activity.

Participants were able to incorporate some of their concerns about wider ecological and global issues in the planning of their game narrative. In interview data, Madiha (parent) describes her own choice to address the negative impact of social media on young people’s wellbeing. She also outlines the topics chosen by her children, specifically Nasrin’s choice to make a game on sea pollution and Xavier’s topic of AI robots taking over the world. On a smaller scale, some participants chose their hobbies or fan interests as game subjects, Ed choosing trains (see Vignette 3) and Maggie, Pearl, Toby, and Clive choosing beekeeping. Interview data surfaced the identification of art as a hobby practice by Ed (child), Nasrin, and Madiha. This was echoed in video data, where both Madiha and Nasrin appeared to favour working with graphical elements and bringing characters to the game. Madiha also created a physical craft collage, which she brought in to be scanned and used as the game’s graphical background.

The purpose of this section is not to exhaustively catalogue initial imported repertoires involving divisions of labour and wider interests; rather, it illustrates characteristics of an important initial stage in a longer process of agency development. At times, the combining of these repertoires with either GDP concepts or technical tools was very rapid. For some participants, the process of blending their interests with those of the game making programme began immediately and intuitively. In interview data, Mark (parent) described Ed (child)’s use of the Piskel graphical art editor as both intuitive and exploratory, appearing to act as a natural progression from his home paper-based sketching processes. Other processes took longer to emerge, requiring more time or active effort to incorporate. While these repertoires entered the activity individually, their significance emerged more fully in the collaborative processes of blending and re-mediation explored in the next section.

Blending repertoires in third spaces

This section explores how repertoires from home were merged with those introduced through the game making process, focusing on the role of playtesting in supporting this blending. The work of DiGiacomo and Gutiérrez (2016) (see Chapter 3) in part examines social interaction in a digital making context and highlights two forms of feedback: material feedback from making activities, which nurtures relational expertise through emerging specialisms, and social feedback, which increases relational agency between participants. Key designed elements of the learning environment of my research afforded immediate feedback (both material and social) during self-playtesting by individuals and pairs. The process evolved to encourage diversity in learner pathways and helped develop specialisms related to growing participant proficiency. As explored in Chapter 6, the structuring of the GDP collection around the MDA game framework, drawing on aesthetics, dynamics, and mechanics, reflected initial participant interests. Some participants developed their imported home interests into areas of game making specialism. For example, several focused on the creation and implementation of graphical assets and level design, motivated by narrative placement in the game via GDPs.

The process of playtesting, beyond a technical evaluation phase (Fullerton, 2018), became a complex community process. Group playtesting of the games of others surfaced existing practices and amplified opportunities for new repertoires, specialisms, and associated identities to propagate. Playtesting can thus be seen as both a process and a third space, suited to the re-mediation of mediational strategies in response to diverse objectives. Playtesting supported both organic and introduced development of hybrid practices that blended the repertoires of young people, parents, and facilitators (Gutiérrez and Vossoughi, 2010). In addition, group playtesting highlighted the relational aspects of both expertise and wider agency, a process that is explored in this section using the data of this thesis.

The development of different styles of playtesting represented new forms of re-mediated strategies incorporating home practices and newly introduced repertoires. Some adults, who developed new technical processes by working through documentation in a methodical manner (see Vignettes 2 and 3), refrained from extensive testing of other games, waiting for others to test their games and carefully observing their responses. Some participants were very social in their playtesting approach and used playtesting as a way to gain an idea of what to add to their game next and to ask for direct help in that process (see Vignette 1). Others built relationships during playtesting in different ways. For example, some gave feedback via kind and supportive comments. Madiha voiced her personal identification with game characters created by others and often said how cute the characters were (Vignette 5). Others embraced a disruptive stance in playtesting, which for some participants provided a chance to break conventions and game design norms of the genre as a way to cause frustration or confusion (Vignette 2). Some children added additional playful elements to the playtesting process. For example, some brought a physicality to the process, clustering in a particular zone of the class, referencing gameplay elements, acting them out, attempting to change the games of others, and engaging in playful tussling as part of resistance to those changes (see Appendix D.2).

The re-mediation and hybridisation of existing and new repertoires was integral to the transformation of participant interests into game making specialisms. My findings support and extend existing research (see Sections 1.2 and 2.2), which indicates that the process of identity formation alleviates barriers to participation in programming communities, as explored in the problem statement of this thesis. The findings of this chapter and Chapter 5 indicate that the role of specialism within playtesting creates helpful system congruencies, supporting the development of novel and effective repertoires through a positive affective relationship to the overall activity. The diversity in making and playtesting behaviours shows the development of a robust community with a variety of modes of participation, echoing the hybrid modes of participation made possible in third spaces (Gutiérrez, Baquedano‐López and Tejeda, 1999) (see Chapter 3.3).

Importantly, social playtesting made the specialisations within individual and pair activity visible at a community level. For example, Vignette 1 describes the emerging specialist focus on game dynamics of Toby (child) and Vignette 5 that of Nasrin (child) and Madiha (parent) concerning graphical design. This visibility of specialism, especially during playtesting, contributed to possibilities for relational agency within the learning community as a whole. As new expertise emerged and was expressed as a form of identity within an individual’s repertoire, it often became available for appropriation by peers as a relational affordance of the learning system. In short, developing the logic and terminology of DiGiacomo, Gutiérrez, and Edwards (2011, p. 33; 2016), the emerging “relational expertise” helped develop relational agency.

Supporting relational repertoire blending and identity

While the previous examples have focused on relational agency between participants, the role of the designer and facilitators is also relevant. Recognising and valuing the emerging areas of specialisation and expertise, both technical and social in nature, helped the development of diverse practices. Specifically, the responsive design revisions outlined in Chapter 5 helped keep games in a working state as participants developed them. Additionally, devoting more time to open playtesting helped reinforce and support the diverse practices of social feedback. I reflected on the possibility that the success of some participants in drawing on imported repertoires could be encouraged or accelerated in others if suitable pedagogical features were added to the learning environment. This is explored in this section via reflection on the roles of supporting helpers and the facilitator interventions of side missions (see Chapter 5).

The role of supporting student helpers and their helping styles took on an important role in the process of repertoire blending. In Phases 2 and 3 (see Chapter 5), I asked students to circulate as participants were engaged in game making as a way of replicating some of the features of playtesting. While it is important to acknowledge the importance of student helpers in the formation of relational agency, given the wealth of existing research on this subject in similar settings (Stone and Gutiérrez, 2007; Kafai et al., 2008; Barron et al., 2009; Roque, 2016; Roque, Lin and Liuzzi, 2016), only a brief summary of activity is included here. I asked helpers to identify and bring to my attention coding problems that were preventing participants from progressing, thus overcoming some parents’ unwillingness to make demands on facilitator time. Student helpers were asked to prompt descriptive reflection by asking participants what features they were working on and to notice and reflect on any distinctive behaviours emerging in participants’ products or practice (see Vignette 1). This parallels a similar study by Stone and Gutiérrez (2007, p. 51), where student helpers highlighted emerging “zones of competency” in learners’ identities and relational expertise. While not part of their given remit, student helpers also communicated to participants innovations in practice made by peers, a reflexive response which helped contribute to relational expertise within the group and thus increased the overall possibility of relational agency.

Turning to address interventions in Phases 2 and 3 which aimed to accelerate the process of relational expertise and repertoire blending, the introduction of side missions (see Chapter 5) made visible emerging repertoires as cultural affordances in a way that increased and legitimised the diversity of learner pathways and overall approaches to participation. This section is limited in scope as, while there are novel and promising elements here5, a detailed exploration is beyond the scope of this thesis. From observation of the emerging specialisms and identities explored above, I created a working typology of participant approaches to playtesting and game making. This grouping became a topic of reflection via a playful game exploring Bartle’s player types (Bartle, 1996). Subsequently, to support these maker types, I created a selection of side missions and presented these together with a wider mission set within a drama frame. Planners like to study to get a full knowledge of the tools and what is possible before they build up their game step-by-step. Social makers form relationships with other game makers and players by finding out more about their work and telling stories in their game. Magpie makers like trying out lots of different things and are happy to borrow code, images, and sound from anywhere for quick results. Glitchers mess around with the code, trying to see if they can break it in interesting ways and cause a bit of havoc. See Appendix D.1 for more details on the evolution of these types. In interview data, participants shared their positive feelings towards both the shared fictional frame of making a game for an audience of judgemental aliens and elements of mischievousness in the social missions within that drama.

The value of the drama narrative and side missions aligns with work on play theory as a technique that gives participants permission to play (Walsh, 2019), legitimising previously peripheral activities and bringing them into the participants’ shared conceptions of the idioculture. The recognition of the hybridity of possible modes of participation increases conceptions of enacted diversity in the community. This strand of thought invites a theoretical examination of the particular value of identity formation via the blending of repertoires of play and design approaches. The role of play as a leading activity is explored by Gutiérrez (2019) as a way to facilitate movement between sites of learning. This invitation to play may be evocative of repertoires already familiar to participants, and thus acts as a helping process to welcome participants into a new collaborative zone of proximal development.

Part Three - Synthesising and reframing findings related to agency

Returning to the gaps in existing research that shaped the focus of this study, this part emphasises not only the importance of analysing socio-cultural approaches to computer game design and programming (CGD&P), but also their potential relevance for wider contexts of project-based computing education and collaborative learning. The following section synthesises key messages from the study and frames them as theoretically consistent with socio-cultural approaches while accessible for use in broader discussions of design and pedagogy.

RQ3 asked, in what ways does participation in CGD&P support the development of agency, particularly through the blending and re-mediation of cultural repertoires in the learning community? Addressing RQ3 directly, and the under-explored area of agency development in existing research in CGD&P, it is of value to re-examine and synthesise the characteristics of the learning design described using agency as a lens. Agency in this game making community is seen as multi-dimensional and as a process located in community participation rather than an individualised property. In this analysis, the concept of relational agency represents an end point achieved through building on and incorporating processes of instrumental and transformative agency. It follows that it is advantageous to highlight relational agency as a guiding principle for varied stakeholders. For example, as an objective for participants to develop, for designers to design for, and for facilitators to facilitate.

This chapter has explored a process of developing relational agency via analysis of the findings that were framed via a staged approach to re-mediating existing repertoires into new repertoires within an emerging game making idioculture. To help conceptualise this goal and process I propose the new term relational agency by repertoire blending (RARB). This term, based on the work of Gutiérrez and others (2007; 2020), mirrors the grammar of Sannino’s (Sannino, 2015b) concept of TADS (transformative agency by double stimulation). It is advanced with a motive to provide an accessible framing and a metaphorical structuring to a complex process.

Narrative description of facilitating relational agency by repertoire blending (RARB)

To consolidate the analysis above, this section outlines RARB as a staged process, making visible how agency develops through repertoire blending. RARB is a process which, in the context of this study, can be usefully described via three stages. In stage one, the motivation is to create an inclusive learning environment where participants are able to import existing repertoires from other spaces in the form of competencies and interests. For some participants, this may involve the use of designed affordances of resources in ways pre-planned by the learning designer via instrumental agency, or they may explore novel uses of the affordances of resources or other features of the wider learning environment through a process of TADS. As participants apply their existing repertoires as they use the new tools available to them, a process of blending is already underway.

Stage two involves a natural melding of these repertoires in the melting pot of a new third space, in this case the game making sessions. This blending process in turn results in novel repertoires, for example rapid digital sketching of pixel art which was a result of home sketching practices meeting a pixel art tool (see Vignette 4). In this research, the repertoire-blending process was facilitated by the favourable conditions provided by regular playtesting and other playful elements of the programme. These emerging making behaviours and specialisms, involving interests and helping behaviours, and resulting from manifestations of instrumental and transformative agency, suit propagation via playtesting and other social and cultural interactions in the space.

In stage three, facilitators can recognise the emergence of novel processes and begin to help other participants adopt those same processes by incorporating them into the learning design or by highlighting the possibilities they offer in other ways. The role of the facilitator here, metaphorically speaking, involves adding ‘yeast’ or other accelerants to allow the body of the emerging idioculture to grow faster by making relational, socio-cultural affordances more visible to all participants. The culture should be kept ‘warm’ by checking that such processes are not overwhelming, that they are optional, and by maintaining a playful environment at this stage to allow this form of relational agency to flourish. The table below summarises these stages, highlighting design characteristics and examples.

| Characteristics of design | Design example and description |

|---|---|

| Stage One - Facilitating participants to import existing repertoires of practice | |

| Allow quick demonstrations of game knowledge | Quick-start activities scaffold learners to alter games and allow learners to show competency |

| Encourage early use of art and music abilities via scaffolded tool use | Learners interested in art can use intuitive pixel art and music editors to quickly integrate their home interests in digital creations |

| Facilitate flexible group sizes to allow importation of relational helping and working repertoires | Use of a foundational game template helps novices get started without help, thus tending towards fewer members in groups and greater project diversity |

| Use a project theme that is relevant to participants | Use of a relevant theme in the project design brief |

| Stage Two - Engendering blending of repertoires | |

| Protection from complexity via technical limitations | Participants benefit from a more relaxed making environment as key design solutions are built into template design |

| Provide feedback mechanisms in the materials of the making process | Use of a code playground providing immediate visible output to code changes made, use of a starting template structured to afford quick code changes that have large visible impact on the game |

| Try to create a level playing field between generations | The use of an unfamiliar text coding process for both young people and adults created a more horizontal power relationship |

| Provide regular social or community feedback on emerging designs as a way to recognise and engender participant specialisms | The use of playtesting allowed for regular feedback (both material and social) from peers and facilitators |

| Stage Three - Recognising and encouraging emerging specialism and identity behaviours | |

| Engendering a low-stress approach and playful environment which encourages participants to express aspects of their identity and wider repertoires | Use of drama games, and playful side missions within a fictional scenario |

| Structuring reflection on relational expertise | Use of maker types, glitchers, social makers, planners, and magpie makers, as a tool to facilitate emerging specialisms, and to communicate the validity of a pluralism of approaches to design and programming |

| Explicit interventions to support the development of new blended helping styles | Use descriptions of helping styles in digital environments to reinforce adaptation of existing home helping repertoires |

Table 7.3 - Summative table illustrating stages of facilitating RARB in this study

Together, the narrative and table provide a structured account of how repertoire blending can be facilitated across stages, linking the development of instrumental, transformative, and relational agency. The next section reflects on how this staged process contributes to broader pedagogical strategies for nurturing agency in creative computing contexts.

From structural scaffolding to social and cultural processes

Having explored the abstract and concrete dimensions of design and facilitation in part one of this chapter, and the development of agency through social and cultural processes in part two, this final section draws these strands together to consider their relationship to the overarching research question: how can pedagogies to support CGD&P be enriched using socio-cultural approaches to enable inclusive learning in non-formal contexts? The discussion moves from analytical interpretation to pedagogical synthesis, offering a conceptual framework that links technical structuring, repertoire blending, and inclusive facilitation. The aim here is not to recap each research question in turn, but to present an integrated perspective on how socio-cultural insights can be translated into a practical design strategy applicable to CGD&P learning environments, and potentially to broader project-based learning contexts.

At this stage, it is also useful to return to the problem statement of the study articulated in Chapter 2. One of the gaps identified in existing research concerned the challenge of communicating a holistic understanding of the learning design that evolved through this project. The following summary addresses this challenge by offering a synthesis of the overall pedagogy, presented in three parts. First, it describes how the REEPPP, RARB, and GDP elements interrelate within a broader pedagogical framework. Second, a graphical representation is introduced to support communication of this model to varied audiences. Finally, a metaphor drawn from the musical process of jamming is explored as a way to communicate key principles of the design in a more accessible and evocative form. This metaphor serves both as an interpretive device and as a bridge to the concluding chapter’s recommendations for practice.

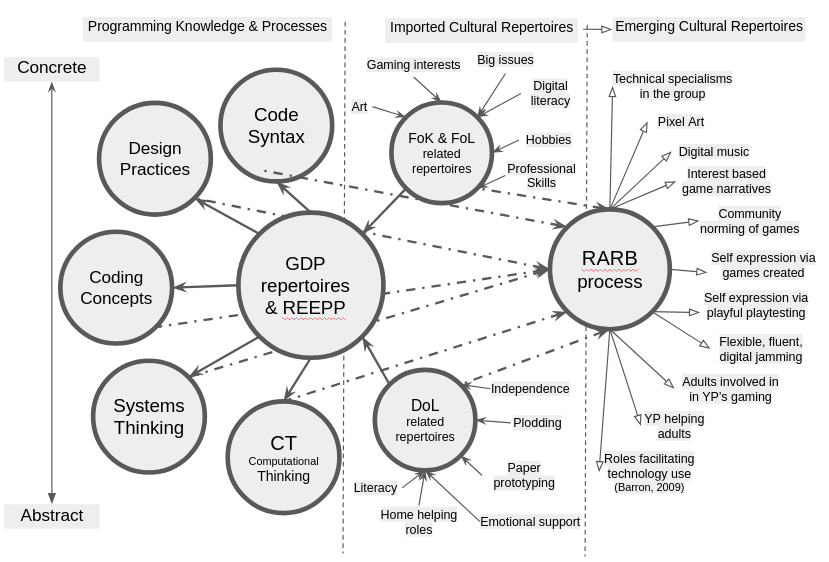

The structural element of the REEPPP approach can be augmented with the socio-cultural elements explored in Part Two of this chapter. To do this, I could propose a logical acronym: collaborative, culturally responsive, remix-enabled, elective, progressive pattern patching (CCRREEPPP). While this term is logical and playful in approach, I have concerns that it may be perceived as cumbersome. Instead, I will focus here on describing the relationship between REEPPP, RARB, and the use of GDPs as gateway concepts. The structural scaffolding provided by the REEPPP framework facilitates the initial stage of the RARB process, where GDPs play a key role as a gateway to abstract and concrete concepts and practices. These can then be blended with imported participant repertoires, resulting in new repertoires manifested through relational expertise and relational agency in a new community of learners. While this complexity is difficult to represent diagrammatically, I have attempted to do so in Figure 7.4, focused on combining the role of GDPs as a gateway concept with the wider re-mediation of diverse imported and emerging repertoires.

Figure 7.4 extends the previous representation in Figure 7.3 of GDPs as a gateway construct. The REEPPP structural framework is added as a foundation of the pedagogy. The gateway role of GDPs to access more personal concepts and practices remains, but more social repertoires are represented within the initial stage of RARB (labelled importing of cultural repertoires). The process of relational agency by repertoire blending (RARB) is represented as a nexus of activity where the re-mediation of other repertoires occurs. Emerging, blended repertoires are represented as a product of that process. Finally, I reverse the polarity, aligning with the CHAT concept of rising to the concrete. This integrated representation provides one way of synthesising the findings and leads into the subsequent metaphorical framing that follows. Together, these forms of synthesis prepare the ground for the concluding recommendations in Chapter 8.

Communicating dimensions of agency and related design concerns via jamming as a metaphor

The previous sections have explored a complex view of participant agency and the process of repertoire development in this learning design. This section reinterprets some of these aspects, in particular the principles in Table 7.3 above, using a metaphorical approach. The use of metaphor here has two functions. The first is to help deepen my analysis via a move to the abstract, searching for communicable generalisations. The second is to aid the accessibility of this research for an audience of practitioners as well as researchers. Given the complex nature of the pedagogy, a metaphorical approach allows a simplified but evocative perspective which communicates the future possibilities of the findings (Gutiérrez, Jurow and Vakil, 2020; Rajala, Cole and Esteban-Guitart, 2023).

Jamming, a term common in music and theatre, describes responsive, improvised, rapid, and fluid responses to collaborators’ ideas and audience reactions (Sawyer, 2003; Pinheiro, 2011). The concept of musical improvisation within jam sessions is a productive way to explore a tension between freedom and structure within this research. As with the harbour metaphor of Chapter 5, a jamming process has structure and designed limitations (Rosso, 2014), but beyond that it provides affordances to encourage learners to evolve their own play processes as a form of transformational and relational agency. In a jam session, foundational, technical infrastructure is provided in the form of drums, microphones, and amps. More established regulars act as facilitators of the musical performance process. A jam on a micro level can refer to a musical piece which follows conventions. The piece may be based on a familiar, popular genre, such as a slow blues jam. Common jam genres include blues, rock, and jazz. Jam pieces are often based on variations of a song familiar to the community of musicians (often referred to as standards). The structure, tempo, and key in which it is performed form a base guiding improvisation. A jam is also a process, for example, within a jam session, bringing your own style to build on existing structures is generally welcomed as long as it blends. The process is augmented by the group interaction present in the musical jam, where music makers pick up techniques from others. Visual and verbal encouragement is often present in successful jam nights to encourage newcomers. If a jam session is regular, local popular standards emerge. This provides opportunities to hear them played regularly, allows potential future participants to hear different versions, and even sing along in the audience, a useful form of peripheral participation.

Linking this metaphor to the process of game making, the process of improvisation based on a prototype of a familiar created genre is present in the half-baked platformer game template. This research has outlined the value of an authentic audience made up partly of peer makers to motivate the development of repertoires of practice in a game making context. Additionally, the possibility of blending established repertoires with those brought by peer players is also a motivation in both the context of the metaphor and this research.

Parallels between the guiding frameworks advanced in this chapter and the metaphorical description of the jamming process above, and the harbour metaphor in Chapter 5, help conceptualise and communicate the diverse processes at play. The structural elements, particularly those of the harbour metaphor, are represented in the REEPPP approach. The harbour theme evokes imagery of the loading of materials which align with the importation of repertoires stage of the RARB process outlined above. The broad description of the musical jam as a space for self-expression, peer learning, and innovation communicates the essence of the RARB process at work. Together, these metaphors serve as a final synthesis and as a link to the concluding section of this chapter.

Conclusion

This chapter has synthesised and reframed findings across three interrelated strands: the structuring of abstract and concrete knowledge in CGD&P, the development of agency through cultural and social processes, and the articulation of a holistic pedagogical framework grounded in socio-cultural theory. Together, these strands form a response to the overarching research aim of understanding how learning environments can be designed to support diverse, interest-driven participation in game making. In particular, the analysis has addressed RQ3 by showing how learner agency and game maker identity developed through the blending of repertoires, and by examining the pedagogical strategies that supported this process.

The first part of the chapter examined how gameplay design patterns (GDPs) supported shifts between levels of abstraction in computing activity. This was developed through the proposal of the REEPPP approach, a structural framework that scaffolds progression while maintaining participant autonomy. The second part reframed earlier findings through the lens of agency, with particular focus on relational and transformative processes supported by repertoire blending and third space dynamics. Drawing on concepts from socio-cultural theory, the analysis explored how participants developed new specialisms, identities, and helping styles through joint activity, reflection, and playful social feedback. In the third and final part of the chapter, these insights were drawn together into a composite pedagogical model combining the REEPPP structure, the RARB process, and the use of GDPs as gateway concepts. Metaphorical framings, particularly the harbour and jamming metaphors, were introduced as communicative tools to support understanding of these complex processes and to make them more accessible to varied audiences.

While the findings highlight forms of agency development within this study’s context, the frameworks proposed here are not intended as universally prescriptive. Rather, they offer principles and strategies that can be adapted to other CGD&P settings and potentially to broader project-based learning environments. These elements of the chapter offer a theoretically grounded but practically oriented pedagogy that emphasises participation, identity, and learner agency in CGD&P contexts. Chapter 8 will build on this by identifying the study’s key contributions to theory and practice, summarising its methodological innovations, and outlining directions for future research and application.

Chapter References

Barendregt, W. et al. (2017) ‘Intermediate-level knowledge in child-computer interaction: a call for action’, in Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children (IDC ’17). Stanford, California, USA: ACM, pp. 7–16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3078072.3079719.

Barron, B. et al. (2009) ‘Parents as learning partners in the development of technological fluency’, International Journal of Learning and Media, 1(2), pp. 55–77. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1162/ijlm.2009.0021.

Barron, B.J.S. et al. (1998) ‘Doing with understanding: Lessons from research on problem- and project-based learning’, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 7(3-4), pp. 271–311. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.1998.9672056.

Bartle, R. (1996) ‘Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit MUDs’, Journal of MUD research, 1(1), pp. 19–26.

Brennan, K. and Resnick, M. (2012) ‘New frameworks for studying and assessing the development of computational thinking’, in Proceedings of the 2012 annual meeting of the American educational research association, Vancouver, Canada, p. 25.

Curzon, P. et al. (2014) Developing computational thinking in the classroom: a framework. Swindon: Computing at School. Available at: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/369594/.

Curzon, P. et al. (2020) ‘Using semantic waves to analyse the effectiveness of unplugged computing activities’, in Proceedings of the 15th Workshop on Primary and Secondary Computing Education. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (WiPSCE ’20), pp. 1–10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3421590.3421606.

DiGiacomo, D.K. and Gutiérrez, K.D. (2016) ‘Relational equity as a design tool within making and tinkering activities’, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 23(2), pp. 141–153. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2015.1058398.

Edwards, A. (2005) ‘Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner’, International Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), pp. 168–182. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.06.010.

Edwards, A. (2009) ‘From the systemic to the relational: Relational agency and activity theory’, in Learning and expanding with activity theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 197–211.

Edwards, A. (2011) ‘Building common knowledge at the boundaries between professional practices: Relational agency and relational expertise in systems of distributed expertise’, International Journal of Educational Research, 50(1), pp. 33–39. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2011.04.007.

Engeström, Y. (1996) ‘Development as breaking away and opening up: A challenge to Vygotsky and Piaget’, Swiss Journal of Psychology [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Development-as-breaking-away-and-opening-up%3A-A-to-Engestr%C3%B6m/1d4071c3a3506d0d41d058f4029d65102e25db0a (Accessed: 6 March 2025).

Eriksson, E. et al. (2019) ‘Using gameplay design patterns with children in the redesign of a collaborative co-located game’, in Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Interaction Design and Children. Boise ID USA: ACM, pp. 15–25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3311927.3323155.

Fullerton, T. (2018) Game design workshop: A playcentric approach to creating innovative games. 4 edition. Boca Raton: A K Peters/CRC Press.

Gutiérrez, K. et al. (2019) ‘Learning as movement in social design-based experiments: Play as a leading activity’, Human Development, 62(1-2), pp. 66–82. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1159/000496239.

Gutiérrez, K.D. (2008) ‘Developing a sociocritical literacy in the third space’, Reading Research Quarterly, 43(2), pp. 148–164. Available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.43.2.3.

Gutiérrez, K.D. et al. (2019) ‘Youth as historical actors in the production of possible futures’, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 26(4), pp. 291–308. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2019.1652327.

Gutiérrez, K.D., Baquedano‐López, P. and Tejeda, C. (1999) ‘Rethinking diversity: Hybridity and hybrid language practices in the third space’, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 6(4), pp. 286–303. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039909524733.

Gutiérrez, K.D., Jurow, A.S. and Vakil, S. (2020) ‘A utopian methodology for understanding new possibilities for learning’, Handbook of the cultural foundations of learning, p. 330.

Gutiérrez, K.D. and Rogoff, B. (2003) ‘Cultural ways of learning: Individual traits or repertoires of practice’, Educational Researcher, 32(5), pp. 19–25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032005019.

Gutiérrez, K.D. and Vossoughi, S. (2010) ‘Lifting off the ground to return anew: Mediated praxis, transformative learning, and social design experiments’, Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2), pp. 100–117. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347877.

Heathcote, D. and Bolton, G. (1994) Drama for learning: Dorothy Heathcote’s mantle of the expert approach to education. Dimensions of drama series. ERIC.

Höök, K. and Löwgren, J. (2012) ‘Strong concepts: Intermediate-level knowledge in interaction design research’, ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 19(3), pp. 1–18. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/2362364.2362371.

Hopwood, N. (2022) ‘Agency in cultural-historical activity theory: strengthening commitment to social transformation’, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 29(2), pp. 108–122. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2022.2092151.

Isaac, G., Barma, S. and Romero, M. (2022) ‘Cultural historical activity theory, double stimulation, and conflicts of motives in education science: Where have we been? (2012-2021)’, Revue internationale du CRIRES : innover dans la tradition de Vygotsky, 5(2), pp. 86–94. Available at: https://doi.org/10.51657/ric.v5i2.51287.

Kafai, Y.B. et al. (2008) ‘Mentoring partnerships in a community technology centre: A constructionist approach for fostering equitable service learning’, Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 16(2), pp. 191–205. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260801916614.

Lodi, M. and Martini, S. (2021) ‘Computational thinking, between Papert and Wing’, Science & Education, 30(4), pp. 883–908. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00202-5.

Maton, K. (2013) ‘Making semantic waves: A key to cumulative knowledge-building’, Linguistics and Education, 24(1), pp. 8–22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2012.11.005.

Matusov, E., von Duyke, K. and Kayumova, S. (2016) ‘Mapping concepts of agency in educational contexts’, Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 50(3), pp. 420–446. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9336-0.

Papert, S. and Turkle, S. (1990) ‘Epistemological pluralism and the revaluation of the concrete’, Signs, 16(1). Available at: http://www.papert.org/articles/EpistemologicalPluralism.html (Accessed: 1 November 2017).

Pea, R.D. (1987) ‘Logo programming and problem solving’. Available at: https://telearn.hal.science/hal-00190546v1.

Pinheiro, R. (2011) ‘The creative process in the context of jazz jam sessions’, Journal of Music and Dance, 1(1), pp. 1–5.

Quintana, C. et al. (2004) ‘A scaffolding design framework for software to support science inquiry’, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(3), pp. 337–386. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1303_4.

Rajala, A., Cole, M. and Esteban-Guitart, M. (2023) ‘Utopian methodology: Researching educational interventions to promote equity over multiple timescales’, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 32(1), pp. 110–136. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2022.2144736.

Resnick, M. et al. (2005) ‘Design principles for tools to support creative thinking’, in Creativity support tools: Report from a US national science foundation sponsored workshop. Available at: http://repository.cmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1822&context=isr (Accessed: 14 March 2017).

Resnick, M. (2020) ‘The seeds that Seymour sowed’, Medium, 16 October. Available at: https://mres.medium.com/the-seeds-that-seymour-sowed-c2860379617b (Accessed: 25 February 2025).

Resnick, M. and Rusk, N. (2020) ‘Coding at a crossroads’, Communications of the ACM, 63(11), pp. 120–127. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3375546.

Resnick, M. and Silverman, B. (2005) ‘Some reflections on designing construction kits for kids’, in Proceedings of the 2005 conference on Interaction design and children. ACM, pp. 117–122. Available at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1109556 (Accessed: 9 May 2015).

Roque, R. (2016) Family creative learning : designing structures to engage kids and parents as computational creators. PhD Thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available at: http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/107577 (Accessed: 30 October 2018).

Roque, R., Lin, K. and Liuzzi, R. (2016) ‘“I’m Not Just a Mom”: Parents developing multiple roles in creative computing’, in Proceedings of the International Conference of the Learning Sciences. Available at: https://repository.isls.org//handle/1/177 (Accessed: 30 October 2018).

Rosso, B.D. (2014) ‘Creativity and constraints: Exploring the role of constraints in the creative processes of research and development teams’, Organization Studies, 35(4), pp. 551–585. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613517600.

Sannino, A. (2015a) ‘The emergence of transformative agency and double stimulation: Activity-based studies in the vygotskian tradition’, Learning, culture and social interaction, 4, pp. 1–3.

Sannino, A. (2015b) ‘The principle of double stimulation: A path to volitional action’, Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 6, pp. 1–15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.01.001.

Sannino, A. (2022) ‘Transformative agency as warping: How collectives accomplish change amidst uncertainty’, Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 30(1), pp. 9–33. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2020.1805493.

Sawyer, R.K. (2003) Group creativity: Music, theater, collaboration. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers (Group creativity: Music, theater, collaboration), pp. ix, 214.

Sentance, S., Waite, J. and Kallia, M. (2019) ‘Teachers’ experiences of using PRIMM to teach programming in school’, in Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education. Minneapolis MN USA: ACM, pp. 476–482. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287477.

Stone, L.D. and Gutiérrez, K.D. (2007) ‘Problem articulation and the processes of assistance: An activity theoretic view of mediation in game play’, International Journal of Educational Research, 46(1-2), pp. 43–56. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2007.07.005.

Waite, J. et al. (2016) ‘Abstraction and common classroom activities’, in Proceedings of the 11th Workshop in Primary and Secondary Computing Education. ACM Press, pp. 112–113. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/2978249.2978272.

Waite, J.L. et al. (2018) ‘Abstraction in action: K-5 teachers’ uses of levels of abstraction, particularly the design level, in teaching programming.’, International Journal of Computer Science Education in Schools, 2(1), p. 14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21585/ijcses.v2i1.23.

Waite, J. and Sentance, S. (2021) Teaching programming in schools: A review of approaches and strategies. Raspberry Pi Foundation.

Walsh, A. (2019) ‘Giving permission for adults to play’, Journal of Play in Adulthood, 1(1), pp. 1–14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.660004179753289.