05. Findings - Design Narrative

Findings: Design Narrative

Chapter introduction

This chapter presents a design narrative that traces the evolution of the learning environment developed in this research across different phases of implementation. The narrative approach adopted here is informed by design based research (DBR) traditions and the analytical tools of third generation activity theory (3GAT), as outlined in Chapter 3. This chapter demonstrates how changes in tools, documentation, and pedagogical strategies were shaped by participant need, focusing in particular on phases one to three of the research process, as explained in Chapter 4, where these phases were identified as providing the richest and most analytically productive data.

Design narratives are a useful DBR technique for describing situated, context-sensitive changes to an intervention over time (Hoadley, 2002; Bell, 2004). Here, the narrative is grounded in the concrete details of the research setting and practices, and attends closely to how formative redesigns emerged in response to barriers encountered by participants. While Hoadley (2002) covers motivations of design narratives, there are no set forms. My design narrative is a blend of contextual information, facilitator reflections, justifications of design changes, and interwoven vignettes drawn from close observations of video data. By narrating the emergence and evolution of the learning design, this chapter contributes to the overall methodological project of the thesis, to develop a participatory, tool-mediated environment guided by a synthesis of CHAT and DBR processes.

The chapter begins with a situated vignette that introduces the activity and its participants. This is followed by three major sections, each focused on a cluster of contradictions identified during the analysis. These cover tensions related to technical tools and accessibility, issues of navigation and documentation, and cultural or identity based challenges in the coding process. Each section presents a sequence of problem identification, design response, and analysis of the resulting outcome or change. To do this, each section draws on session notes, participant feedback, artefact analysis, and observations from the researcher’s journal. A discussion section follows, providing initial interpretations of these findings, which are developed in subsequent chapters.

Vignette locating the game making activity

To open this chapter, I present a summary of Vignette 1. The purpose is to ground the reader in the evolving design through a demonstration of indicative activity from the perspective of a young participant in the process. This scene offers a humanising and situated entry point to a detailed exploration of the wider project. The fuller vignette, showing how learner motivation, intergenerational collaboration, and playful tool use unfolded in context, is included in the special appendix chapter containing vignettes of activity1. As this chapter traces the development of the learning design through a sequence of design decisions and responses to emerging tensions, it focuses on Phases 1–3 of the project, which represent a continuous period of experimentation with text-based coding tools and supporting resources.

Phase 1 involved an exploratory process using a mixture of non-code tools alongside an early code playground environment, with minimal supporting documentation. Phases 2 and 3 built on this foundation through the sustained use of a code playground, a JavaScript game framework, and a pixel art editor, with Phase 3 extending this approach through the introduction of additional social missions (see Section 5.5.3) within the wider process. Taken together, these phases capture the emergence of core tools, practices, and design responses that are central to the design narrative developed in this chapter. The vignette takes place at the start of the session in the latter stages of Phase 2, shortly after I had made a brief opening announcement, reminding participants that it was the last coding session before the showcase event where games were shared publicly in the university building foyer to adult students. The tools used in this vignette are explored in section 5.3.2.

Toby, a child participant, had been working independently for around five minutes of the session. On Toby’s right, Mick (facilitator and researcher) was helping Veronica, demonstrating how to access two different forms of help in the form of code examples and step by step tutorials. On his left, grandparents Pearl and Clive were working on their own game (within earshot). Toby tests his game by playing through its many different levels, showing fluidity and skill. At times during playtesting, Toby undertakes a process of changing the game code to alter his level layout. The immediate audience of his peers appears to influence his design decisions. Subsequently, Toby invites other group members to play his game, initiating and responding to conversations about the difficulty of his game design. He makes a comment to a peer while self playtesting his game: “I’m just going to have one go of beating this (his own game). It’s 21 levels in it. So Yeeeah.” A student helper also notes the idiosyncratic nature of his level design and comments: “Is yours the one where level one is harder than level three? … I like that.”

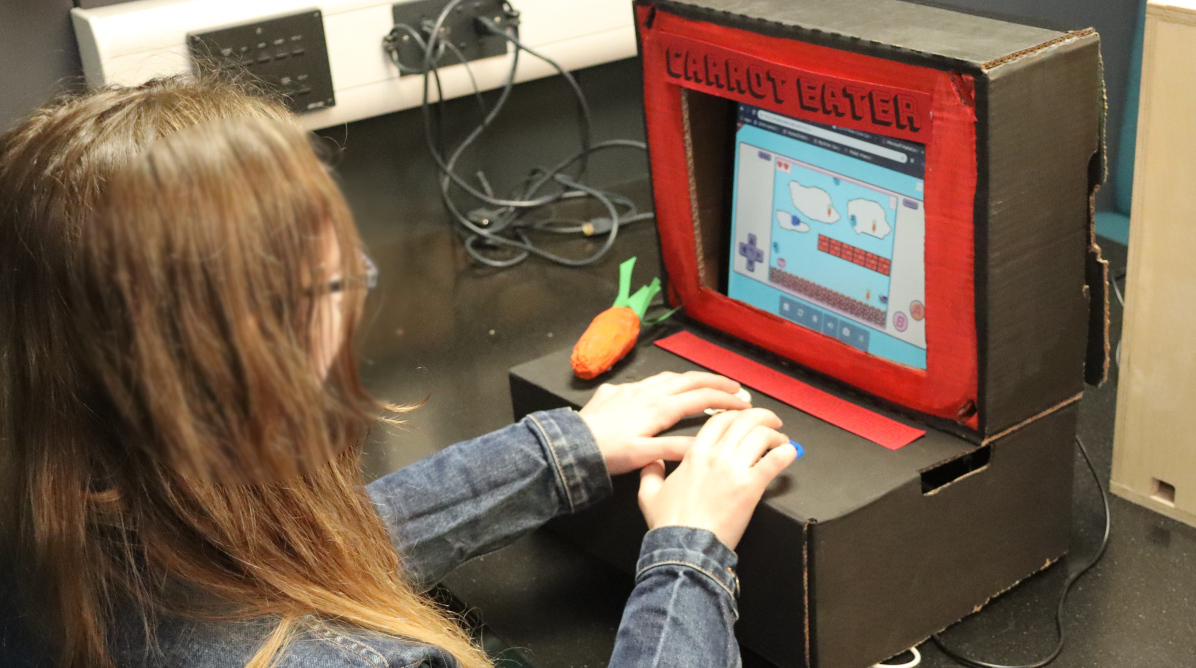

Vignette 1 includes diverse elements of activity which occur at a nexus of intersecting activity systems (see Chapter 4). Toby’s activity is focused sometimes as part of a wider, community scope, and at times on an individual level to make practical changes to his game. Figure 5.1 illustrates one aspect of the object of the wider system, working towards a game showcasing activity in the foyer of the university building where games are shared with the students in the building. Within this activity, Figure 5.1 shows a homemade cabinet surrounding a laptop computer.

Narrative exploration of key areas of contradictions emerging in the game making learning design

In line with the theoretical framing established in Chapter 3, contradictions are understood as historically and structurally embedded misalignments between elements of an activity system, often made visible during periods of change or innovation (Engeström, 1999). Following Kuutti (1995) and Engeström (2011), tensions, barriers, and disruptions which emerge in practice are treated as surface-level manifestations of these deeper contradictions within and between activity systems. These manifestations may take the form of technical difficulties, motivational conflicts, or mismatches between participant expectations and other systemic elements shaping the activity. The following sections of this chapter examine three key areas of contradiction.

The first area of contradiction addressed includes tensions arising from the introduction and evolution of technical tools in the learning design, particularly the shift in software practices between P1 and P2. The second focuses on a contradiction related to navigation and supporting documentation during P2. The third explores cultural and identity-based tensions in coding participation, an area highlighted in Chapter 1 as a significant barrier to inclusion.

Contradiction area 1: involving organisational issues and the use of game programming and asset authoring tools

In this section, I analyse journal notes, participant feedback, and the changes in tools and resources between P1, which was highly experimental, and P2, which included a more complete implementation of the introduced resources. This section (as do the subsequent two) begins with a composite description of activity, summarises key tensions and resulting conflicts, and outlines the responses they provoked.

Email communication inviting participation and describing the proposed workshop activities set an expectation of parents being involved in “families to take part in a Game Making club to learn how to make video games together” and this was restated in the first session. In the early stages of P1, working groups formed organically, broadly along family lines, with three mixed-age groups of roughly five participants. These groups began to define their game ideas during these relatively unstructured early planning sessions. My initial focus was to create a welcoming, low-pressure environment for exploring the process of making games in a way that allowed participants to follow their own interests. To achieve this, I used several activities unrelated to computer coding to scaffold the game design process. Each family had access to a laptop with vintage arcade games installed, and early sessions included time for playing and discussing these retro games, particularly focusing on describing their component parts guided by the Moveable Game Jam process (see Section 2.5.3 ). Other activities included brainstorming game story scenarios, creating pixel-art characters on paper, and making craft collages for game backgrounds. These low-tech activities involving diverse non-coding processes helped surface ideas, supported collaborative group dynamics, and eased participants into the creative space without the pressure of unfamiliar digital tools2.

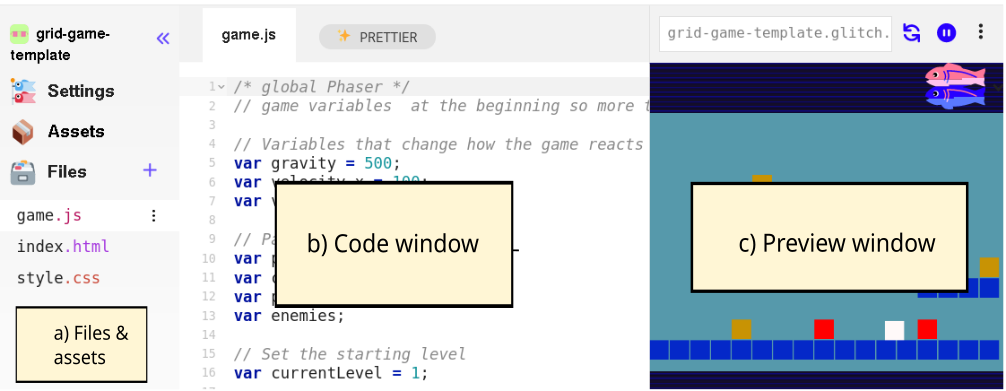

I postponed introducing code editing tools until around week five, prompted by concerns about overwhelming participants and my own ability to support unstructured coding from first principles. I had previously chosen a game design framework, Phaser.js (encountered through participation in the Mozilla community). At this stage I introduced a simplified game template featuring just a character, ground, a hazard to avoid, and a star to collect, illustrating common tropes of a simple retro platform game3. A code playground tool proved initially productive in scaffolding the early coding experience of participants working on web-based games4. Both code playground tools used in P1–3 shared a similar layout, which is common to code playgrounds in general (see Figure 5.2).

The three areas shown in Figure 5.2 represent a visual and technical structuring of a web project: with the ability to create and upload files as assets in area (a), to view and edit the code in area (b), and to preview the resulting game in area (c). The decision to use a code playground was guided by the need to provide a high level of support to participants, given my motivation to encourage authentic engagement with text code rather than a block coding approach (Chesterman, 2015). While the affordances of the code playground ameliorated some of the barriers associated with text-based coding (see Section 1.2.5), associated challenges in this area remained for participants.

In P1, once participants began engaging with code, several tensions quickly surfaced. Differing levels of ability and interest in implementing code led groups to specialise. Some participants with greater confidence or prior experience took on coding tasks, while others focused on graphical game assets, narrative planning, or sound elements. While I wanted participants to be able to follow their interests, this total dis-engagement with coding was not optimal (see Section 5.3.3). At this point my ability to support coding activities became a limiting factor. Whole-group demonstrations were largely ineffective: attention drifted, and groups progressed at different speeds, requiring different support at different times. Without in-tool help or the kinds of code syntax support provided by block coding environments, participants had few scaffolds to rely on. Learners frequently required one-to-one support to make even minor additions to their games. They relied heavily on me as their primary source of help, further increasing the facilitation workload. As a result, support bottlenecks emerged and some participants stalled early in their projects. My journal notes describe these sessions as increasingly difficult to manage.

In line with CHAT analytical processes, I now synthesise emerging tensions as a contradiction. The use of a professional text-code language and framework was a contributing factor. While simplified, the structure of the starting template was still relatively complex for novices and offered no easy way into experimentation as advocated by a tinkering or bricolage approach (see Section 2.2). Many learners had ambitious ideas for their projects that were either beyond the scope of the framework or not realistic given their novice level. Regarding peer learning, while some learners became aware of each other’s programming work, it was difficult to adapt bespoke additions from one project to another thus limiting the scope of peer helping processes.

These tensions reveal an underlying contradiction in the activity system between the object of creating expressive, technically functioning games and the mediating means available to support that objective. In summary, the use of an authentic text-based code environment aggravated a misalignment between participants’ ambitions, their actual skill levels, and the support structures in place within the software toolset. At the same time, the mediational role of a single facilitator in P1 proved insufficient to sustain steady progress within project work and to support diverse learner needs, resulting in friction and delay. This contradiction pointed to the need for redesigned tool affordances and wider scaffolding that could better support the object of creative game development.

Turning to the response to this conflict, one initial adaptation was a non-technical one. After one session in P1, I emailed participants, expressing that I felt daunted by the task of helping integrate the disparate creative elements being produced into cohesive game projects, a process which I felt responsible to facilitate. Within the email, I asked parents for support in organising and bringing more order to group and planning processes5. Subsequently the group planning process improved, with participants using a written wish-list of game features to start to divide up and prioritise activities. The self-organisational abilities and tenacity of families freed up more of my time to support technical issues in the remaining sessions.

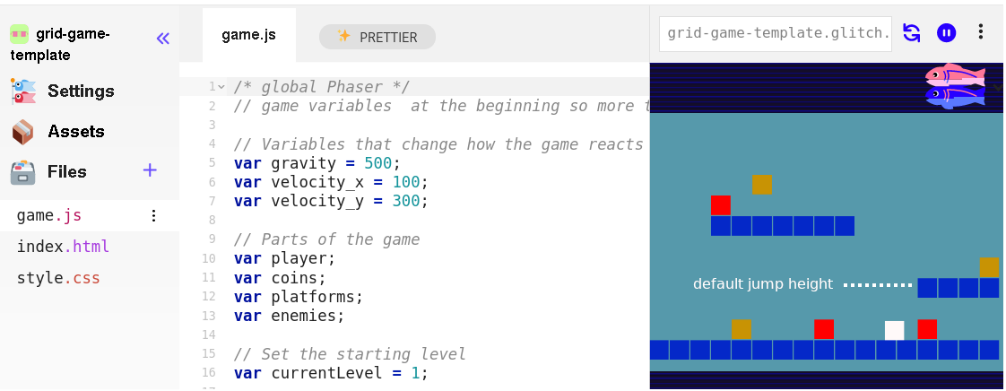

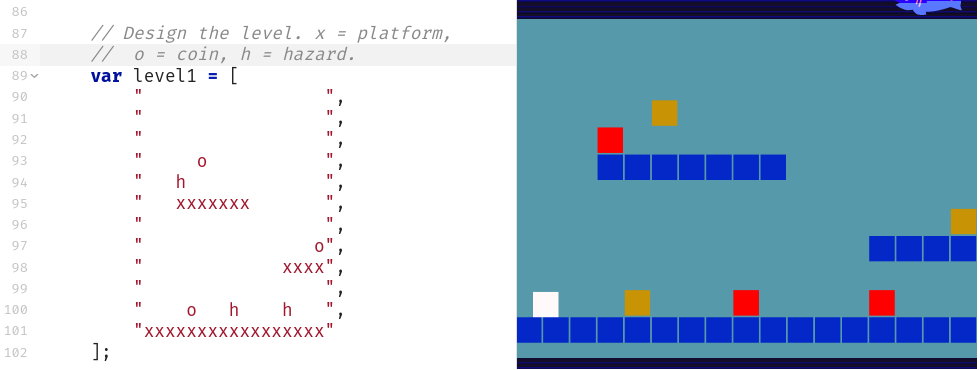

The contradiction outlined above also shaped a series of design adaptations to tools used between P1 and P2. Recognising the need for scaffolding without over-prescription, I developed a revised starter game template with greater scaffolding, including repositioning key variables at the start of the game code and embedding comments to highlight lines intended for modification. The process of developing the affordances of the starter game involved close attention to learners’ first encounters with the game and its underlying code. In subsequent testing, this game template was introduced to learners with a prompt to play a broken game. They were asked to identify in what way the game was broken and then invited to look at the code to try to fix the game (e.g. to make changes to progress). Participants would try to jump up to the platforms in the game but find that they could not jump high enough to progress. Figure 5.3 below shows a white square as a player, red squares are hazards to be avoided, and yellow squares are rewards which must be collected to progress to the next level. A white line is shown indicating how high the player character can jump.

The following section shifts from narrative description to focused articulation of the Phase 2 toolset as a design response to the contradictions that surfaced in Phase 1. While Phase 1 was intentionally exploratory and involved a wide range of tools and practices, Phase 2 represented a deliberate narrowing of this landscape, with the number of suggested tools reduced significantly6. This reduction was not a simplification of learning aims, but a design move intended to stabilise participation, reduce navigational overhead, and make core design actions more visible and accessible.

I offer the following overview to give the reader an in-depth picture of the design affordances and adaptations being carried out. In keeping with the exploratory and design-based nature of the study, this section does not aim to demonstrate learning impact or efficacy, but to document how specific design decisions shaped the conditions for participation and subsequent activity. The Phase 2 toolset was organised around a small number of tightly integrated design features, each intended to reduce navigational complexity while foregrounding key actions within the game making process.

The code playground functioned as a central entry point, providing a place to view and play the starting template and a remix button which, when clicked, created a new version of the project that could be adapted. This allowed participants to begin working immediately with a functioning game, while maintaining a clear pathway for modification and experimentation (see Figures 5.2 and 5.3).

The overall file structure was deliberately simplified, so that participants only needed to alter a single text-based code file. An older version of Phaser.js was selected, allowing for simplified syntax in object and function construction and thereby reducing the complexity of the instructions required to make visible changes to gameplay.

Editable variables were positioned at the start of the main JavaScript file, enabling small changes to produce rapid and noticeable effects in the game. The starter templates included visible parameters for player movement, enemy speed, and image and sound assets, supporting quick experimentation and reinforcing connections between code, values, and on-screen behaviour.

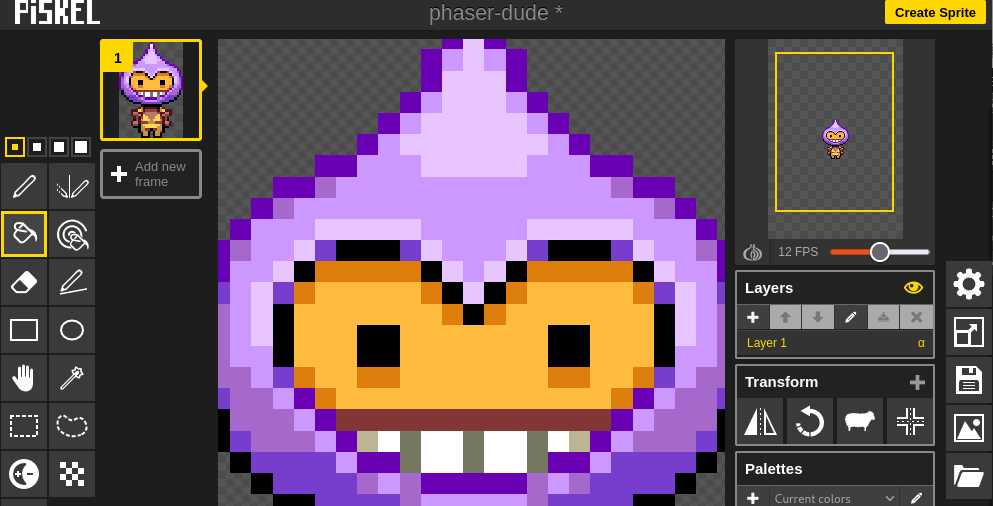

Visual asset creation was supported through the use of block graphics and the external Piskel tool (see Figure 5.4). Generic coloured blocks within the template encouraged participants to design and substitute their own graphics. Working across tools required participants to download and reupload assets, supporting key digital literacy practices related to file handling and asset management beyond the immediate coding environment.

Level design was scaffolded through a graphical structure embedded within text-based code. Drawing on research highlighting the value of visual approaches in novice multimedia programming (Guzdial, 2004; Resnick et al., 2009), a grid-based representation was used to support editing of level layouts, as shown in Figure 5.5. A more detailed account of design considerations related to the template structure is included in the technical appendix, supporting replication by other practitioners7.

This section now changes perspective to summarise and analyse some of the ways in which the adaptations in the design detailed above helped address the corresponding tensions. In line with the exploratory nature of the thesis, the aim is not to prove the efficacy of the intervention, but to explain its role in the iterative process. However, broad summaries of impact are included to help contextualise the later sections.

The starting template reduced the difficulty and time required to initiate a game project. This contributed to a significant shift in working practices from P2 onwards, characterised by smaller working groups, normally pairs or individuals. In addition, the process of starting with a working game and altering existing affordances within the template allowed participants to begin sharing their emerging games with others immediately, which contributed to the concurrent increase in time spent on peer playtesting during this phase. Selecting a reduced toolset in P2 helped prevent participants from being overloaded by the diversity of tools in play and also led to greater alignment of experience across the group. The greater similarity of participant experience and the underlying technical structure of the games appears to have been a contributing factor to the observed increase in peer exchange of skills and knowledge.

The technical adaptation of the text-based level editing grid (see Figure 5.5) had a specific impact on both the coding experience and the wider learning environment. The ability for individuals and pairs to make quick changes to the game templates through the affordances described in the previous section appeared to build their ownership over these fledgling games. Vignette 1 shows Toby designing many levels of varying difficulty, making the experience of playing his game distinct from others. This individuality is noted and encouraged by a student helper (see Vignette 1 extract in the previous section).

I now discuss the previously articulated features of the learning design in relation to existing research, beginning with the use of supporting code templates in programming education. To start, I focus on alignment within past research rather than extension. The template design is an example of a “half-baked” microworld (in the form of a game) (Kynigos, 2007; Kynigos and Yiannoutsou, 2018), and aligns broadly with the UMC framework (Lee et al., 2011). The work of Kynigos et al. (2018) on the concept of half-baked microworlds and games shares a similar focus on the motivational aspect of incomplete game affordances to drive initial engagement. This motivation spurs and shapes activity in the early making stages of this learning design, aligning with the use and modify stages of the UMC approach (Lee et al., 2011) (see Section 2.3.3). The use of a template that introduced hands-on engagement with coding tools early in the process helped avoid the mismatch between participants’ planning and the technical limits of their novice abilities, thus providing an early reality check. Small code changes that produced large visible differences in game behaviour, appearance, or difficulty align with a long-standing principle in HCI research that feedback is motivating for users (Malone, 1982; Bernhaupt, Isbister and De Freitas, 2015).

Turning to the aspect of authenticity8 in the learning design, it is valuable to re-examine the factors driving my choice of JavaScript (which comprises a foundational component of websites and smartphone applications) and Phaser (a professional, open source game making framework). Specifically, this choice relates to the potentially empowering impact of exposing participants to authentic technologies and concepts, which underpin the creation of everyday digital objects that participants interact with, in hands-on, exploratory processes. Ratto (2011) explores this strand via critical making, a process that playfully brings forward Latour’s (2005; 2008) ideas of shifting from matters of fact to matters of concern by revealing taken for granted artefacts as deliberately designed objects. This was evident in conversations between participants where they expressed a sense of inspiration or engagement with previously unknown technologies. For instance, exchanges demonstrated a growing appreciation for the complexity behind professional games, based on their perception of the effort required for their own simple game projects.

Pearl: It just shows you what goes into these games. Student Helper 3: Think about how much effort goes into. Pearl: You just take things for granted don’t you?

While my design aim was in part to reduce coding syntax errors9, part of the goal was also to lessen the anxiety and frustration often experienced by novice coders (Denny, Luxton-Reilly and Tempero, 2012). I did not wish to remove the possibility of learners making mistakes entirely. Even these small changes involved potential syntax errors, but because these simple expressions were surrounded by other lines modelling the correct syntax, participants were often able to correct mistakes without facilitator support. Thus, this careful structuring of the template appeared to mitigate the challenges of syntax errors.

Contradiction area 2: contradictions associated with project navigation and use of documentation

This section outlines a contradiction associated with the need for and introduction of supporting documentation to scaffold the game making process. In P1, participants followed divergent creative pathways using a diverse set of tools, but this came at the cost of a sense of overall coherence and shared understanding of the process. In P1, group organisation coalesced around the creation of wish lists of game features, which acted as mediating tools to coordinate between different team members and to request facilitator support for implementing them via code structures. Between P1 and P2, I reflected on how this process could be developed into a more coherent approach to documentation that could still support this style of project organisation.

In P2, a reduction in the average size of working groups and a subsequent increase in the number of game coding projects led to increased demand on my time as a technical troubleshooter. At this stage, while the in-tool scaffolding provided by the code template accelerated production for learners significantly (Laurillard, 2020), participants still required direct support from me when adding new code structures, causing delays and participant frustration due to the limited time I could offer each group. Early in P2, resources to support implementation were driven by specific participant requests. However, unlike in P1, due to greater similarity in the underlying code structures, the supporting resources created for one project now became suitable for reuse in others. As such, as P2 progressed, a library of short, stand-alone instructional documents began to accumulate.

A recurring tension noted in my journal during this period concerned the clash between divergent participant learning paths and the need for technical support. This was compounded by observations related to whole-class teaching input demonstrating coding issues and solutions, which consistently yielded low engagement. I surmised that participants intuitively experienced these attempts at class teaching as not immediately relevant, at odds with their preferred hands-on working styles, and therefore disruptive to the flow of their making. This observation resonates with the work of Repenning et al. (2015) (see Section 2.4), who describe engagement-related barriers they attribute to a principles-first approach. The authors describe the risk of this approach plainly as participant boredom. Within this phase, I identified a key challenge, that of how to support progress given my limited facilitator time, without losing the important pedagogical feature of participant choice over their pathway. I also struggled to reconcile an additional tension between this responsive approach to providing documentation and requests from some parents for resources involving background concepts and explanations of coding constructs.

Together, these challenges surfaced a contradiction between an important component of the object of the activity (learner-led game creation) and the evolving rules and mediating artefacts intended to support that process. The activity system lacked a shared, structured way for participants to orient themselves in the process, or to develop and reuse successful code patterns without the input of facilitator mediation. Thus, the flexibility of the environment, initially a boon for participant engagement, became problematic. This contradiction appeared to be a double bind (Engeström, 2001): how could I provide greater support via documentation detailing implementation and underlying principles without compromising the responsiveness to the learner pathways that was foundational to the ethos of my approach? This contradiction drove extensive revision in the learning design concerning methods of technical support.

Recalling my organisational crisis in P1 outlined in the section above, in response to my email asking for help, parents made suggestions including: the use of a visible and shared list of game features that were being worked on, and documentation to support the implementation of code that explained underlying principles and foundational code structures. The suggestion of the list of game features, used as both a shared organisational tool and as the basis for providing supporting documentation, became relevant in addressing the contradiction outlined above. Thus, early in P2, I used this dual function (of organisation and documentation) as a guiding principle to structure and present supporting resources in the form of themed features (game design patterns), which users could choose from, allowing them to take on features in the order that they chose. From this point onwards, resources addressing the contradiction outlined above evolved rapidly, resulting in the creation of three main sources of documentation: quick start cards, written instructions, and code snippets. I now describe the process of creating these varied supporting documentation resources and the purposes they served.

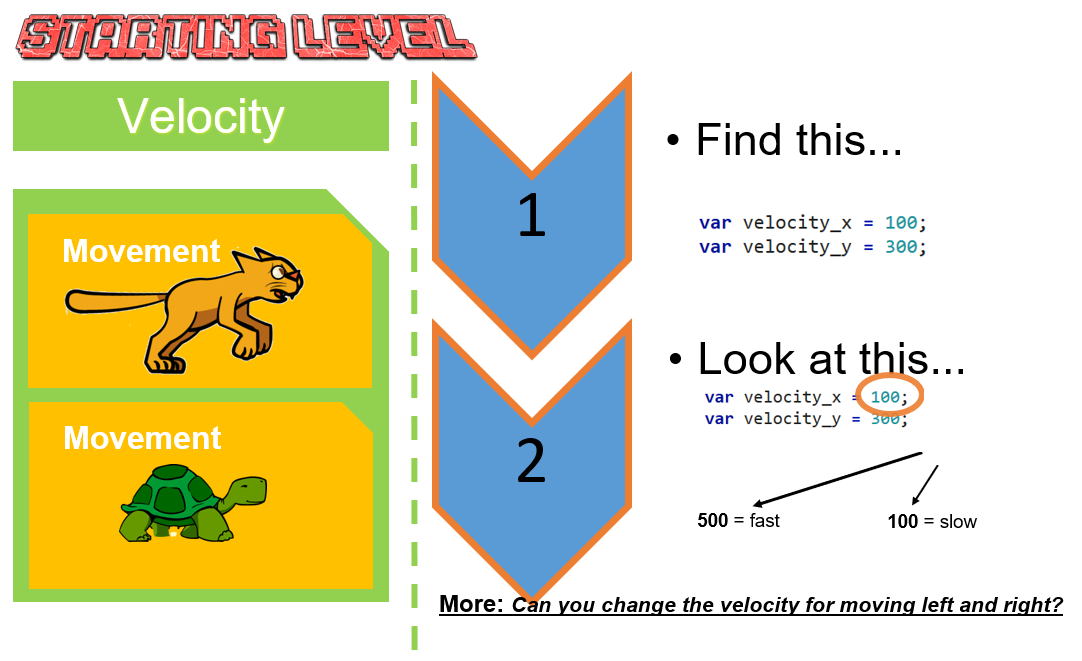

Quick start cards were initially developed to support one-off sessions and to allow rapid experimentation with the starter game of P2, drawing on my past experiences as a facilitator. They were designed to let participants choose challenges based on areas of interest and difficulty. Quick start cards (see Figure 5.6) were A5-sized printouts highlighting the key affordances of the template, involving game mechanics such as movement, jumping, level design, and a challenge to swap out the look of one or more characters by designing pixel art and replacing the line of code that adds the asset to the game. These printed resources highlighted key lines of code and demonstrated how they could be altered to impact game behaviour.

The cards supported participants’ initial interaction with the code in a way that further developed the Use and Modify stages of the UMC framework (Franklin et al., 2020). They allowed participants to get started with the template game with less in-person support from facilitators, due to the strongly scaffolded interaction with the code and the relatively minimal changes needed. While the levels of difficulty of each task were detailed on the card, participants could approach them in their preferred order. Thus, this process scaffolded simple coding tasks while also facilitating choice over learner pathways.

To further reduce dependence on my time as a facilitator, I wrote supporting documentation in a step-by-step format for each code example. In the early stages of P2, learners accessed these documents through a shared Google Document with links and brief descriptions. I continued developing new projects and producing printable instructions to support these code snippets, ensuring that each snippet linked to a descriptive chapter and vice versa.

While the use of code examples or snippets10 is a common professional practice in problem-solving (Yang et al., 2017), their use by novice learners presents challenges related to relevance, consistency, and accessibility (Treude and Robillard, 2017). Difficulties experienced by participants in P1 in understanding and applying abstracted code snippets from the Phaser documentation website prompted me to create more tailored resources for P2. These bespoke, stand-alone code projects demonstrated annotated code features within a playable game project based on the starter game template, allowing participants to copy and paste the relevant code sections into their own projects. Projects illustrated requested game features such as gameplay design patterns, including jumping on an enemy to zap it and making a moving enemy. To help learners situate the code within the correct structure, all projects used the core game template and included only the new code required for each feature.

To meet participants’ requests for foundational coding knowledge, I created step-by-step chapter resources guiding users to code a core game template structure from first principles11. While this linear format did not fully align with my choice-driven approach, I envisioned it as supplementary reinforcement for learning outside of sessions, which indeed some participants did take up.

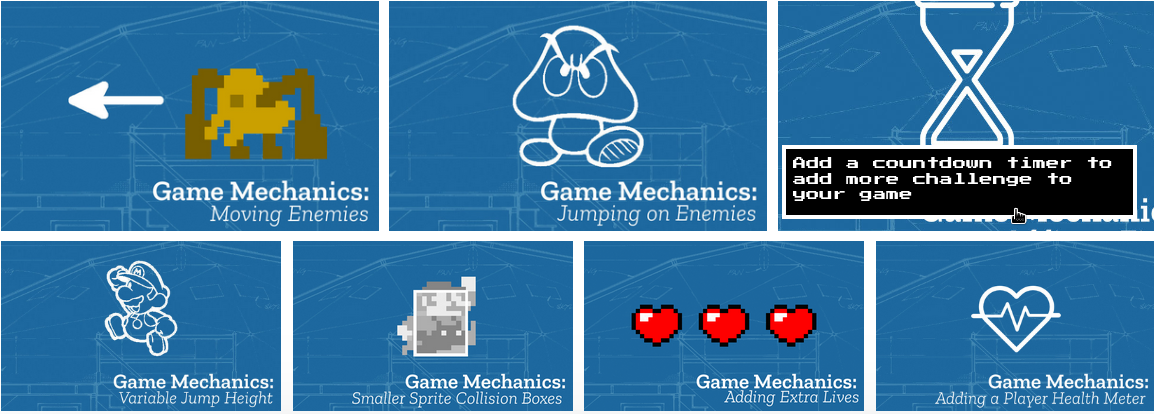

I experimented with ways to present these feature choices in an accessible, visually engaging format. Concerned that multiple documentation formats could lead to confusion, I created a centralised hub, structured around these graphical representations of the game features, to host both snippets and tutorial chapters, with the aim of making navigation more intuitive and orienting documentation around participants’ gameplay experience. Figure 5.7 shows a screenshot of the webpage created which served as a menu of GDPs. Table 5.2 below provides a more complete categorisation of gameplay design patterns contained in this menu and supporting resources.

Given that analysis of participant interaction with resources structured around GDPs is developed more extensively in Chapter 6, discussion of the concepts here in relation to other research is brief. These findings align with the thematic organisation of these patterns to develop a shared understanding of game making concepts within a coding community (Björk and Holopainen, 2005). For the documentation hub described above, I grouped gameplay design patterns into categories based on academic and professional interpretations of game elements (Tekinbaş and Zimmerman, 2003; Salen, Tekinbas and Zimmerman, 2006; Schell, 2008; Olsson, Björk and Dahlskog, 2014), as well as participants’ evolving requests for game features. Specifically, these patterns were themed in a way that aligned with the MDA (mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics) game element framework explored in Chapter 2. The final categorisation used in P4 is shown in Table 5.2.

| Game Mechanics | Game Polish | Game Space | Challenge Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Add Static Hazard | Add Graphical Effects | Change Design of Levels | Gain Points when Collecting Food |

| Add an Animated Enemy | Add Sound Effects | Add More Levels | Add a Timer |

| Jump on Enemy to Zap them | Add a Soundtrack (Music) | Change Shape of Levels | Collect all Food before Progressing |

| Double Jump | Add a Game Story with Messages | Change the Background Image | Power-up – Higher Jump |

| Moving / Patrolling Enemies | Add a Game Story with Messages | Change the Background Image | Power-up – Player Speed |

| Moving / Following Enemies | Animate your Player’s Movements | Key and Door | Random Doubling Enemies |

| Make Player Immune |

Table 5.2 - Categorisation of gameplay design patterns used in P4

While Chapter 2 surfaced research on using collections of gameplay design patterns to support learning in game design (Holopainen et al., 2007; Holopainen, 2011; Eriksson et al., 2019), this work did not relate directly to supporting CGD&P. Other research led by Repenning and Basawapatna (2010; 2010), which did incorporate GDPs within a CGD&P pedagogy, was lacking in its approach to implementing the concept of just-in-time learning within project-based learning (Riel, 1998), where access to supporting documentation is provided based on learner need. Thus, the structuring of the collection of GDP resources outlined here, in response to requests for new features from participants, represents a valuable contribution in addressing the contradiction related to structurally supporting diverse learner pathways addressed in this section.

Contradiction area 3: tensions and barriers in cultural aspects of the game making activity

This section addresses an area of contradiction related to cultural aspects of the game making activity, which, while discussed last in this chapter, is foundational to the thesis. At times during the interventions, in line with existing research (see Section 1.2), some participants experienced alienation from the process of coding. Early in P1, I incorporated several non-coding techniques to encourage a positive, relaxed atmosphere and create an inclusive learning environment. These included playing and analysing retro arcade and console games, drama games as session warm-ups, sketching pixel art on paper, digital pixel art creation, loosely structured ideation sessions to decide on themes, and sessions on music-making and audio effects creation using accessible tools. While this wide diversity of activities was later streamlined in subsequent phases due to time constraints, in line with existing research (Peppler and B. Kafai, 2009; Kafai and Burke, 2015), my observations suggested the initial impact of these more accessible creative approaches on the general culture of the group was positive, in terms of overall affect and engagement. It was the transition away from a period characterised by widespread use of these non-programming techniques toward one more dominated by text-based coding and the use of related tools that appeared to engender a sense of exclusion for some participants.

This alienation is now illustrated using a case study of one family consisting of Anastasia, the mother, and her two daughters, one at the lower end of the 8–12 age range and one at the upper end. While this family actively participated in non-coding activities, tensions emerged when the coding framework was introduced and its limitations became clearer. The structure of a two-dimensional game did not support a key gameplay idea that the younger child had imagined during the ideation stage, specifically exploring a three-dimensional landscape from the point of view of a bee avatar (see Appendix C.2). This realisation was very upsetting to the child and required extensive negotiation, led by Anastasia and with support from me, to explain the limitations of the beginners’ coding course. This episode echoed the previous tensions described in the Contradiction 1 section above related to tool use but was amplified by the strong emotional response of the child.

Two sessions later, the whole family experienced a sense of alienation. As the phase progressed, an organic division of labour had occurred, with some members of the wider group continuing to focus on graphical and audio asset creation while others worked on incorporating these assets and ideas into the code framework. As participants moved beyond early-stage ideation and asset creation, the flexible, diverse, and decentralised working practices gave way to a narrower set of expected competencies. There was progressively less for the non-coders to do. During participant feedback, Anastasia shared that, in one session, they had arrived a little late and, after observing other participants deeply immersed in problem-solving with text-based coding tools, felt surrounded by a process of hardcore coding (participant’s phrase) that they felt disconnected from.

Experiences of marginalisation were not limited to this family. In interview data, parent Maggie noted, “I was worried we (her and her son Jay) neglected Toby,” referring to this stage where some members within each game making group were focused on implementing the code while others were left nominally continuing graphical asset creation. In my journal, I noted that group work at this stage felt disjointed, with non-coders left with little to do, and a feeling that the previously playful culture was transforming into something more serious. I reflected on the fragility of learners’ positive affect and the risk of alienation, particularly during the transition from the planning and sketching phase to the coding phase.

Turning now to the surfaced tensions, barriers, and resulting contradictions, these reflections show two strands of tension between activity system elements. One tension is between the object of working together and the emerging norms requiring close engagement with the technical aspects of coding. Another tension concerned the division of labour. To participate fully in later design stages, participants would need to engage with text-based code regardless of their previous (and perhaps preferred) working practices. In addition, given that coding activities were ongoing, attempts to incorporate these team members at this stage would be disruptive to those existing divisions of labour. These tensions, combined with previously explored cultural barriers to coding, expose a contradiction between the object of the activity (inclusive game making allowing diverse creative contributions) and the cultural layer of activity (Engeström, 1999).

The contradiction and resulting feelings of alienation occurred despite a learning environment that included diverse and inclusive activities (outlined above). This suggests that treating such activities as an “add-on” creates difficulties. The process of introducing accessible non-coding activities helped with acculturation to the game making process in general, but as text-based coding became necessary later, this only delayed alienation for some participants. Indeed, the process potentially heightened frustration if participants had invested in a process they were later excluded from. In P1 feedback, the parent Anastasia suggested more hands-on exploration with the tools of production before being required to make creative decisions (see Appendix C.2). As such, addressing this contradiction required rethinking not only the technical scaffolds, as outlined above, to enable early interaction with tools, but also the need to accommodate ongoing contributions in visual design, sound production, and narrative development in a more balanced fashion.

Addressing the design response, as previously outlined (see Sections 5.3.1 and 5.3.2), changes in tools and documentation had a positive impact. The use of a template and quick start cards facilitated shareable games from early stages and created varied points of entry into the activity. Participants were increasingly able to work either individually or in small groups, often alongside family members. This helped reduce role-based exclusions, such as in the case above, where non-coding contributions became marginalised. In particular, structuring resources around an episodic process of applying one GDP after another shifted the design pattern away from a linear design-build-test (see Section 2.3.2) progression and allowed for greater balance between coding and non-coding activities.

Two other design interventions were introduced in P2 and P3 to respond to the tensions outlined above: the use of social coding practices within playtesting, and the introduction of side missions. These strategies served to realign cultural dimensions of the activity system and supported more inclusive and flexible forms of participation. Turning first to social coding within playtesting, a longer period with a functioning game and the ability to make small iterative changes allowed each tweak to be self-tested and shared with others. As participants spent more time playtesting both their own and others’ games, playtesting evolved beyond instrumental testing into a significant social and cultural practice. By the midpoint of P2, it had become a key site of peer exchange, prompting spontaneous sharing of advice, assets, and debugging strategies.

Video data captured instances of participants expressing frustration when errors rendered their games unplayable (see Vignette 2). While such frustration was natural, as a facilitator, I felt a strong sense of urgency when this occurred. I prioritised supporting participants with broken games to make them playable again so they could benefit from playtesting. When reflecting on this sense of urgency, I noted my emerging understanding of the varied benefits of playtesting. I had observed that different people gained different things from the process: some used playtesting as a time to generate ideas, others to socialise, and others to have fun. Journal notes, later confirmed by video and interview data, described a variety of playtesting behaviours, including forming social connections (often parents), chaotic clusters of excited young people (see Appendix D.2 for a fuller description), and quirky design choices that bent game conventions. These examples, in part, demonstrate productive chaos, and participants were clearly experiencing flow in their playful playtesting. The characteristic of flow in a social and cultural setting felt especially evocative to me as a facilitator, in a way that links with Basawapatna’s work within Scalable Game Design (SGD) research on proximal flow (2013), which blends flow theory and social engagement within learning (2013). The evolving role of playtesting is developed further in Chapter 6 in relation to GDPs, fluency, and agency.

In P3, I began gently but deliberately intervening to support the emergence of these collaborative social coding practices via the use of side missions. The side missions, framed within a drama scenario (Patterson, Chesterman and Ramsey, 2019), aimed to encourage varied playtesting practices. In P3, I introduced a narrative framework to scaffold participant engagement in the form of a fictional scenario: an alien civilisation had contacted the group after seeing the games published in P2. They demanded that participants upload more games so the aliens could assess the worth of the human race12. Within this scenario, participants were assigned printed side missions that were not directly related to game creation, some public and some kept secret, that encouraged forms of interaction and exploration with playtesting similar to those described above. These side missions supported playful social dynamics and aimed to shift the focus away from individual technical mastery toward creativity within a shared community. Examples of these missions are included in Table 5.3.

| Your Alien Mission (social) | Your Secret Alien Mission |

|---|---|

| Find out the names of 3 games that are being made | Change the variables at the start of someone else’s game to make it play in a funny way |

| Make a list of characters in two other games | Replace the images in someone else’s project with something unexpected |

| Find out the favourite computer games of 4 people | Change the level design of someone else’s game to make it impossible using minimal edits |

Table 5.3 – an extract of side missions given as part of the drama scenario

This section concludes with a brief discussion of this area of contradiction (continued in Chapter 7). As discussed in Chapter 2, much of the literature on computing game design and programming (CGD&P) emphasises learners’ personal appropriation of programming concepts, often framed through individual progression or mastery. The learning design presented here offers a different approach, foregrounding the cultural and affective dimensions of participation. By integrating narrative framing, varied social missions to enhance playful playtesting, and role-based reflection activities, the design created space for learners to engage on their own terms.

In line with theory on formative interventions, these missions acted as secondary stimuli, opening up new pathways for agency development (Hopwood, 2022). Their use helped locate observation, playfulness, and curiosity as valid forms of participation, helping to legitimise roles beyond that of a hardcore coder. While here I focus on a specific set of missions and the drama-based approach used to frame them, these interventions can be interpreted as design artefacts that mediated both cultural and affective engagement, making space for diverse learners to see themselves as legitimate participants in the game making space. This broader framing of legitimate participation responds to critiques of overly individualistic orientations in CGD&P and aligns with sociocultural perspectives on learning as relational in nature. Chapter 7 builds on this by analysing how these design features supported the development of learner agency through cultural repertoires, shared roles, and evolving patterns of participation.

Chapter synthesis

This final section discusses features of the design narrative and synthesises elements of the design process into models and metaphors that contribute to the research landscape. Specifically, a stage-based approach is offered as a practical contribution. The learning design is contrasted with UMC and constructionist design principles, highlighting the increased conceptual and practical complexity that arises when using authentic tools and processes. Subsequently, a harbour metaphor is proposed to clarify these conceptual contributions. Finally, a summative table synthesises aspects of systemic contradictions discussed in this chapter. At this stage, discussion related to these models is at times concise, as greater discussion follows in later chapters.

Advancing a stage-based pedagogy structured around GDPs

In the learning design outlined in this chapter, GDPs drive stage-based instructional processes. Adapting terminology from Denner et al. (2019), the shift from P1 to P2 represents a move from a design-build-test to a stage-based approach. The term stage-based here describes a process that introduces code structures and challenges in an initially simplistic, prototypical format for learners to experience and explore, and which are subsequently replaced by more advanced models or complex instances of the task. In this design, this stage-based approach is enacted through participant interaction with increasingly sophisticated documentation and code structures.

The structure of documentation, created in response to participant requests to add new GDPs to their games, evolved from a piecemeal format in P1 to, by the end of P2, a menu of GDP code snippets accompanied by detailed instructional documentation. This progression is shown in Table 5.4.

| Stage | Pedagogical focus | Design focus |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Informally identifying GDPs | Identifying GDPs via an activity of playing games |

| Stage 2 | Quick start cards | The quick start cards supported rapid changes to GDPs highlighted as affordances in the starting game code template |

| Stage 3 | Adding simple GDPs | These additions required only small-scale changes to the template structure |

| Stage 4 | Advanced GDPs | Larger changes, including new functions or fundamental changes to the code |

Table 5.4 – A representation of the staged processes

This stepped approach, which increases the complexity of the object of activity, is explicitly addressed only in limited CGD&P research. The work of Repenning et al. (2015) on SGD operationalises this progression through guiding learners to undertake projects of increasing complexity, each implementing more advanced patterns. However, it differs in that no common template is provided, so learners must start from a blank slate each time. This is significant, as I found in P1 that changes requiring substantial alteration of the underlying code structure were stressful for participants and unwelcome once they had developed familiarity with that structure, thus my approach from P2 onwards of using a common starting template reduces that risk.

The four-stage approach outlined in Table 5.4 shares characteristics with, and offers benefits aligned to, the Use-Modify-Create (UMC) pedagogy (Lytle et al., 2019) (see Chapter 2.3). Stage 1 uses playful game analysis as a precursor to game making (Cornish et al., 2018). Stage 2, through the design of the P2 starting game template, helps participants rapidly build familiarity with code structures and tools (the Use stage of UMC). Stage 3 aligns with Modify, where minimal changes have a large visual or behavioural impact, matching UMC’s guidance to “create choices that show visible and immediate changes” (Lytle et al., 2019, p. 6). The careful scaffolding of early coding experiences described earlier required early and repeated transitions from Use to Modify, helping to overcome possible negative affect related to text-based coding. Stage 4 represents the most advanced level of this stage-based model. This includes implementing a more complex GDP from the menu (requiring new functions or significant changes to the code). The decision to choose from a restricted set of options, rather than create from scratch, aligns with some adaptations of UMC. A further extension still involves the choice to imagine, design, and implement a GDP not included in the menu provided. This is a process that Dan and Toby take on in P3 by adapting the code template to create a Pac-Man like maze game (see Vignette 6).

Discussion in relation to constructionist heuristics

There is strong alignment between the underlying principles of the learning design described above (see Sections 5.3.1 & 5.3.2 in particular) and research on constructionist design heuristics (see Section 2.2). This section outlines these similarities using specific examples, explores divergences related to the role of authenticity in the learning design, and ends with a metaphor based on the findings of this chapter which extends constructionist principles.

Of particular relevance is the constructionist principle to choose black boxes carefully (Resnick and Silverman, 2005). Resnick et al. (2005) describe black boxes as abstractions that simplify or hide complex elements of the production process, creating a scaffolded learning experience while maintaining a boundary between the learner and the challenges of interactive professional coding communities. Based on Laurillard’s (2020) interpretation of constructionist microworlds as being driven by affordances that support user experimentation and concept formation without relying on direct instruction, this learning design aligns with those core characteristics.

However, the structure of the learning design should be interpreted as an adapted form of microworld, marked by greater authenticity and connection to professional coding environments and documentation. When compared to a classic microworld like LOGO’s Mathworld and its use of drawing robots, my design is characterised by relatively porous boundaries between the structured learning environment and external, more authentic coding ecosystems.

One risk of using professional tools with novice learners is that they may experience a form of culture shock, encountering unfamiliar or alienating aspects of coding environments designed for experienced users. The learning design outlined in this chapter helps mitigate that initial shock through the scaffolded elements explored in Section 5.3.1. Following Resnick, my approach still involves choosing black boxes carefully, but my strategy differs: rather than shielding learners from authentic creative tools and communities, I provide guided and supported access to them. This represents a shift in emphasis from restriction to supported exposure. Thus, the relationship between authentic tools and scaffolded processes can be seen as a dialectical tension that should be accounted for, not avoided. The next section develops this point further using a metaphorical framing.

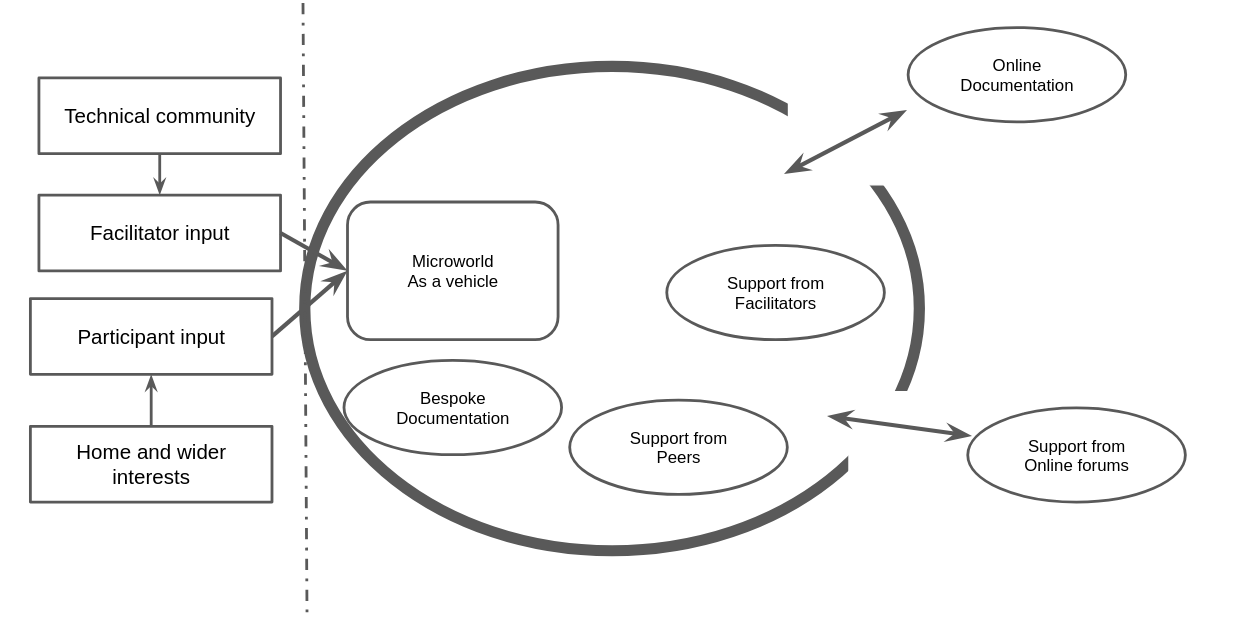

Harbour metaphor

A metaphor of a harbour is offered here to illustrate the points of the previous section and in particular how the designed spaces can balance structure and freedom. Harbours are transitional spaces between land and sea, built to facilitate the movement of people and goods between these domains. In this metaphor, the microworld of the starting template game articulated in this chapter functions as a vehicle for exploration, forming the base of the learning experience. It is designed to support input from technical communities through the lens of the facilitator’s design experiences. This chapter has described how I worked to integrate material from professional communities into the starting template. In addition, affordances within the template design and accompanying resources enabled participants to bring in interests from home into the new learning space.

Figure 5.8 shows a simplified representation of a harbour (centre), with land on the left and sea on the right. Harbours are protective spaces, artificial or naturally occurring, used as safe locations for docking ships. If artificial, protection is provided by walls that extend into the sea to create shelter. In this metaphor, the harbour walls represent restrictive design decisions: the use of a fixed game genre and simplified code structures. While this design employs an authentic, professional text-coding language with its inherent challenges, many design choices were made to protect new users from the complexity of the underlying web technologies. The safe space of the harbour encourages free exploration within its walls, including collaboration with peers, use of bespoke documentation, and facilitator support.

Harbour walls block disruptive forces like large waves but leave gaps to allow ships to move into open waters. The motivational potential of using authentic tools exists in tension with the complexity they bring (Nachtigall, Shaffer and Rummel, 2024). The learning design outlined here helps ease the transition from the protected harbour to the open seas of independent practice. The choppy waters beyond represent the challenges of interpreting and navigating professional-level documentation and community support (see Appendix V.6). This metaphor offers an accessible representation of the design responses to contradictions concerning authenticity. It also begins to show how carefully structured constraints can enable the creative potential for agency development (Rosso, 2014), a theme explored in more detail in Chapter 7.

Initial outputs from the design process

In this chapter the use of a design narrative process informed by DBR practice (Hoadley, 2002) has been employed to share not only the detail of the resulting learning design but also the emerging tensions that drove its evolution and the replicable approach that developed through practice. With that aim in mind, the resources created during the intervention are available online as open and reusable educational resources13, and this section briefly details the most relevant outputs of this process. These are presented here as stabilised artefacts that emerged in response to specific contradictions, rather than as a complete or finalised pedagogy. A facilitator toolkit is available online for a full list of resources generated and guidance on how to reuse them.

Stabilised mediating artefacts emerging from the design process

This section provides a partial snapshot of material artefacts that stabilised during the intervention. A fuller synthesis of methodological and practical contributions is developed later in the thesis conclusion.

Practical resources

As a summary, the following categories of resource emerged in response to the contradictions outlined earlier in this chapter:

- Quick start cards, which scaffolded initial engagement with code and reduced reliance on facilitator intervention

- Code templates, which provided a shared technical structure and supported early experimentation

- Manual chapters, which documented patterns and workflows for reuse and reflection

- Menus of gameplay design patterns, which supported navigation, choice, and staged progression

These resources are available collectively as a facilitator’s toolkit14, which collates materials developed during P2 and P3 and documents their intended use.

Early synthesis and tentative pedagogical modelling

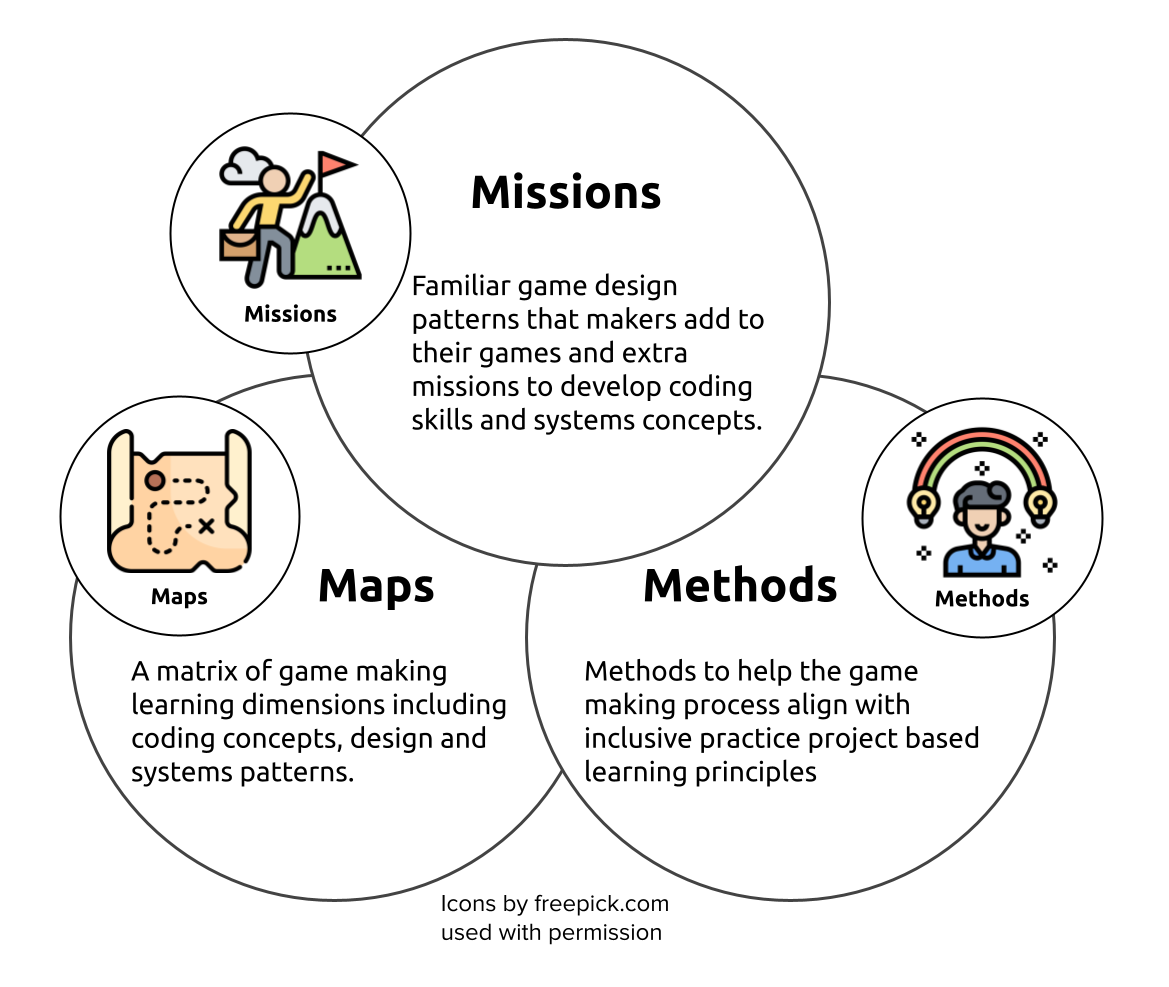

In summer 2020, I began early dissemination of interim findings in a peer-reviewed edited volume (Keane and Fluck, 2023). The resulting chapter presented selected aspects of the learning resources and design to fellow practitioners, participants, and researchers (Chesterman, 2023). In order to make this material accessible to a practitioner audience, I framed key elements of the process used within the research phases as a pedagogic model I called 3M (Missions, Maps and Methods).

The 3M model functioned as a facilitator-facing synthesis, designed to summarise key design principles and motivations rather than to serve as an analytic framework for this thesis. It is shared here (Figure 5.9) to acknowledge this early synthesis and its role in dissemination, while recognising that it simplifies the more complex and contingent design narrative presented in this chapter. A table explaining these elements with more concrete examples is included as Appendix D.3.

Further discussion of how models and frameworks emerged across the study, and their relationship to the core analytic concepts of the thesis, is taken up later in the concluding chapters.

Summative table of emerging tensions and resolutions

Rather than offering a comprehensive catalogue of all tensions identified during the study, this table provides a selective synthesis of the key contradictions examined in this chapter. It draws together the design narrative by showing how particular barriers, tensions, and congruencies surfaced in practice and how they were provisionally addressed through iterative design responses. In doing so, the table consolidates the chapter’s analysis and offers a reference point for the more detailed treatment of gameplay design patterns and learner agency developed in Chapters 6 and 7. Table 5.5 summarises these selected contradictions and the corresponding design responses that emerged through the intervention.

| Tension, Barrier or Congruence emerging | How the design addresses this issue |

|---|---|

| Category One – Software tool use | |

| Congruence: Learners interested in video games are motivated to create their own game. | A common game genre provided a clear motivation and a recognisable end goal. |

| Tension: Guidance needed to change the template, but potential exists for learner disengagement if coding is taught from first principles, especially for younger participants. | Learners start with a half-working minimal game template that requires only minimal code changes to produce noticeable in-game feedback. |

| Congruence: Learners interested in art want to create digital artwork to replace placeholder graphics. | Intuitive pixel art editors support rapid character design, and code template signposting helps incorporation within the game. |

| Category Two – Documentation and navigation | |

| Barrier: Learners take on game genres or features too complex for their current coding ability. | Game type is limited to a single genre; missions are capped in complexity. GDPs are scaffolded to start with low-threshold, high-impact patterns. |

| Tension: Learners become frustrated when they cannot choose their next feature, while facilitator capacity is strained by diverse pathways. | A menu of GDPs enables a flexible order, supporting autonomy and motivation while keeping complexity manageable. |

| Tension: Facilitators may struggle to identify inherent learning outcomes if unfamiliar with game making, while formal skills frameworks can restrict flexibility. | A map of learning dimensions flexibly linked to GDPs helps both learners and facilitators trace progress and identify learning. |

| Category Three – Social and cultural barriers | |

| Congruence: Designing a game for a real audience is experienced as motivating. | Playtesting within sessions offers short-term motivation; end-of-project showcase events help learners prioritise and reflect on progress. |

| Barrier: Learners may feel alienated from coding culture or the tools themselves. | Relatable code structures and role-based fictional scenarios help reduce anxiety and encourage engagement through role-play. |

| Barrier: Participants may avoid written documentation or lack proactive planning skills. | Side missions and extended playtesting time support peer-to-peer sharing, allowing knowledge of GDPs and implementation techniques to circulate informally. |

Table 5.5 - Summary of emerging tensions and design responses

Chapter conclusion

This chapter has explored the complexity of the interacting tools and documentation as they evolved across different phases of the formative intervention process. It has described three contradictions that occurred during an iterative, phase-based approach informed by techniques of DBR and CHAT. The contradictions explored initially focused on technical, and then more social, dimensions of the learning design. Regarding methodology, the emergent and mutual nature of this design process aligns with both DBR principles and CHAT concepts of transformation in tool use arising from both explicit and implicit feedback. The descriptions in this chapter also show that the process was demanding for participants. I was fortunate that the tenacious character of the participants in P1 helped mitigate the challenges posed by beginning with such an incomplete pedagogy. The design narrative above has acknowledged my active input into the direction of the process, in line with an active approach to steering the design towards collaborative learning opportunities (Stetsenko, 2020).

My observations, supported in the following chapter, indicate that the use of a template and a collection of GDPs accelerated the uptake of certain coding fluency practices, which in turn increased the use of collaborative coding processes. This chapter has explored the responsive development of the learning design, focusing on resolving barriers to coding and aligning with existing research principles, particularly the UMC process and constructionism. It emphasised the potential and challenges of utilising professional tools within scaffolded environments, and described the pivotal role of learner-led design decisions in motivating coding practices and promoting social collaboration. The next chapters extend this analysis by examining the cultural and social dimensions of game making in more depth. Chapter 7 examines the impact of emerging community processes on participants’ agency, while Chapter 6 employs video data to describe and analyse the diverse applications of GDPs.

Chapter References

Basawapatna, A.R. et al. (2013) ‘The zones of proximal flow: Guiding students through a space of computational thinking skills and challenges’, in Proceedings of the ICER ’13: International Computing Education Research Conference. ACM, pp. 67–74. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/2493394.2493404.

Basawapatna, A.R., Koh, K.H. and Repenning, A. (2010) ‘Using scalable game design to teach computer science from middle school to graduate school’, in Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education (ITiCSE ’10). ACM Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/1822090.1822154.

Bell, P. (2004) ‘On the theoretical breadth of design-based research in education’, Educational Psychologist, 39(4), pp. 243–253. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3904_6.

Bernhaupt, R., Isbister, K. and De Freitas, S. (2015) ‘Introduction to this special issue on HCI and games’, Human–Computer Interaction, 30(3-4), pp. 195–201. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2015.1016573.

Björk, S. and Holopainen, J. (2005) Patterns in game design. 1st ed. Hingham, MA: Charles River Media (Charles River Media game development series).

Chesterman, M. (2015) Webmaking using JavaScript to promote student engagement and constructivist learning approaches at KS3. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20180831105358/http://digitalducks.org/blog/project-report-webmaking/ (Accessed: 19 March 2016).

Chesterman, M. (2023) ‘Game making and coding fluency in a primary computing context’, in T. Keane and A.E. Fluck (eds) Teaching Coding in K-12 Schools: Research and Application. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 171–187. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21970-2_12.

Cornish, S. et al. (2018) The Game Jam Guide. Carnegie Mellon University. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/6686948.v1.

Denner, J., Campe, S. and Werner, L. (2019) ‘Does computer game design and programming benefit children? A meta-synthesis of research’, ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 19(3), pp. 1–35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3277565.

Denny, P., Luxton-Reilly, A. and Tempero, E. (2012) ‘All syntax errors are not equal’, in Proceedings of the 17th ACM annual conference on Innovation and technology in computer science education. Haifa Israel: ACM, pp. 75–80. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/2325296.2325318.

Engeström, Y. (1999) ‘Activity theory and individual and social transformation’, in Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, and R.-L. Punamäki-Gitai (eds) Perspectives on Activity Theory. Cambridge University Press, pp. 19–38.

Engeström, Y. (2001) ‘Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization’, Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), pp. 133–156. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747.

Engeström, Y. and Sannino, A. (2011) ‘Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organizational change efforts: A methodological framework’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(3), pp. 368–387. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811111132758.

Eriksson, E. et al. (2019) ‘Using gameplay design patterns with children in the redesign of a collaborative co-located game’, in Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Interaction Design and Children. Boise ID USA: ACM, pp. 15–25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3311927.3323155.

Franklin, D. et al. (2020) ‘An analysis of use-modify-create pedagogical approach’s success in balancing structure and student agency’, in Proceedings of ICER ’20: International Computing Education Research Conference. Virtual Event New Zealand: ACM, pp. 14–24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3372782.3406256.

Guzdial, M. (2004) ‘Programming environments for novices’, in S. Fincher and M. Petre (eds) Computer Science Education Research. Taylor & Francis.

Hoadley, C.P. (2002) ‘Creating context: Design-based research in creating and understanding CSCL’, in Computer Support for Collaborative Learning. Routledge.

Holopainen, J. et al. (2007) ‘Teaching gameplay design patterns’, in Proceedings of ISAGA (2007).

Holopainen, J. (2011) Foundations of gameplay. PhD thesis. Blekinge Institute of Technology.

Hopwood, N. (2022) ‘Agency in cultural-historical activity theory: strengthening commitment to social transformation’, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 29(2), pp. 108–122. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2022.2092151.

Kafai, Y. and Burke, Q. (2015) ‘Constructionist gaming: Understanding the benefits of making games for learning’, Educational Psychologist, 50(4), pp. 313–334. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2015.1124022.

Keane, T. and Fluck, A.E. (eds) (2023) Teaching coding in K-12 schools: Research and application. Cham: Springer International Publishing. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21970-2.

Kuutti, K. (1995) ‘Activity Theory as a potential framework for human- computer interaction research’, in Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human-computer interaction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 17–44.

Kynigos, C. (2007) ‘Half-baked logo microworlds as boundary objects in integrated design’, Informatics in Education - An International Journal, 6(2), pp. 335–359. Available at: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=60016 (Accessed: 15 September 2018).

Kynigos, C. and Yiannoutsou, N. (2018) ‘Children challenging the design of half-baked games: Expressing values through the process of game modding’, International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2018.04.001.

Latour, B. (2008) ‘A cautious Prometheus? A few steps toward a philosophy of design (with special attention to Peter Sloterdijk)’, in ‘Networks of Design’, Annual International Conference of the Design History Society. Universal Publishers, pp. 2–10.

Laurillard, D. (2020) ‘The significance of Constructionism as a distinctive pedagogy’, CONSTRUCTIONISM 2020, 29.

Lee, I. et al. (2011) ‘Computational thinking for youth in practice’, ACM Inroads, 2(1), pp. 32–37. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/1929887.1929902.

Lytle, N. et al. (2019) ‘Use, modify, create: comparing computational thinking lesson progressions for STEM classes’, in Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education. Aberdeen: ACM, pp. 395–401. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3304221.3319786.

Malone, T.W. (1982) ‘Heuristics for designing enjoyable user interfaces: Lessons from computer games’, in Proceedings of the 1982 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’82). New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (CHI ’82), pp. 63–68. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/800049.801756.

Nachtigall, V., Shaffer, D.W. and Rummel, N. (2024) ‘The authenticity dilemma: Towards a theory on the conditions and effects of authentic learning’, European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(4), pp. 3483–3509. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-024-00892-9.

Olsson, C.M., Björk, S. and Dahlskog, S. (2014) ‘The conceptual relationship model: Understanding patterns and mechanics in game design’, in Proceedings of the digital games research association. DiGRA, pp. 1–16.

Patterson, R., Chesterman, M. and Ramsey, A. (2019) ‘Drama and STEM’, in H. Caldwell and S. Pope (eds) STEM in the Primary Curriculum. 1 edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Learning Matters.

Peppler, K. and B. Kafai, Y. (2009) ‘Gaming fluencies: Pathways into participatory culture in a community design studio’, International Journal of Learning and Media, 1(4), pp. 45–58. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1162/ijlm_a_00032.

Ratto, M. (2011) ‘Critical making: Conceptual and material studies in technology and social life’, The Information Society, 27(4), pp. 252–260. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2011.583819.

Repenning, A. et al. (2015) ‘Scalable game design: A strategy to bring systemic computer science education to schools through game design and simulation creation’, Trans. Comput. Educ., 15(2), pp. 11:1–11:31. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/2700517.

Repenning, A., Webb, D. and Ioannidou, A. (2010) ‘Scalable game design and the development of a checklist for getting computational thinking into public schools’, in Proceedings of the 41st ACM technical symposium on Computer Science education. Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA: ACM Press, p. 265. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/1734263.1734357.

Resnick, M. et al. (2009) ‘Scratch: programming for all’, Communications of the ACM, 52(11), p. 60. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/1592761.1592779.

Resnick, M. and Silverman, B. (2005) ‘Some reflections on designing construction kits for kids’, in Proceedings of the 2005 conference on Interaction design and children. ACM, pp. 117–122. Available at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1109556 (Accessed: 9 May 2015).

Riel, M. (1998) ‘Education in the 21st century: Just-in-time learning or learning communities’, in Proceedings of the fourth annual conference of the emirates center for strategic studies and research. Abu Dhabi.

Rosso, B.D. (2014) ‘Creativity and constraints: Exploring the role of constraints in the creative processes of research and development teams’, Organization Studies, 35(4), pp. 551–585. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613517600.

Salen, K., Tekinbas, K.S. and Zimmerman, E. (2006) The game design reader: a rules of play anthology. MIT Press.

Schell, J. (2008) The art of game design: A book of lenses. 1 edition. Amsterdam ; Boston: CRC Press.

Stetsenko, A. (2020) ‘Radical-transformative agency: Developing a transformative activist stance on a marxist-vygotskyan foundation’, Revisiting Vygotsky for social change: Bringing together theory and practice, pp. 31–62.

Tekinbaş, K.S. and Zimmerman, E. (2003) Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Treude, C. and Robillard, M.P. (2017) ‘Understanding stack overflow code fragments’, in Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME). IEEE, pp. 509–513. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSME.2017.24.

Weibel, P. and Latour, B. (2005) Making things public : Atmospheres of democracy. Edited by P. Weibel and B. Latour. MIT Press. Available at: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02057286 (Accessed: 30 August 2020).

Yang, D. et al. (2017) ‘Stack overflow in github: Any snippets there?’, in 2017 IEEE/ACM 14th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), pp. 280–290. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1109/MSR.2017.13.

-

All Vignettes are located in a special appendix called Appendix V. See Vignette 1 within that section for a fuller description and interpretation of Toby’s activity. ↩︎

-

The activities are described in more detail in section 5.3.3 later in this chapter. ↩︎

-

See Appendix E for a greater level of detail of my initial design choices including that of Phaser.js as a JavaScript game framework. ↩︎

-

Code playgrounds are online environments used to test and share code projects primarily for web-based projects using HTML, JavaScript and css technology. ↩︎

-

This email included in Appendix C.1 illustrates a pivotal moment in my understanding of the limits of my role as facilitator of an open process and the need to impose limitations. This aspect is explored later in Section 5.3.1. ↩︎

-

Tools used in P1 included several audio and music making tools, Scratch as a graphical editor, and varied non software tools. See Appendix D.1.? ↩︎

-

See here: https://micksphd.flossmanuals.net/tech_appendix/template/ ↩︎

-

In this context of technical tools, authenticity refers to technology which is used beyond education-only settings: e.g. in professional or enthusiast communities. ↩︎

-

Syntax errors in computer coding equate to grammatical errors in other languages (e.g punctuation errors). ↩︎

-

Code snippets are code examples extracted from context in a way designed to facilitate reuse and often shared online as a community resource. ↩︎

-

See Chapters 1-7 of the main manual within the Faciliator’s Toolkit here: https://3m-phaser.flossmanuals.net/docs/ ↩︎

-

The drama scenario based on performing activities in role (Patterson, Chesterman and Ramsey, 2019), is included in the Facilitator’s Toolkit see Appendix E.1. ↩︎

-

For P2-3 resources see here: https://3m-phaser.flossmanuals.net For P4-5 resources see here: https://3m-makecode.flossmanuals.net ↩︎

-

Facilitator Toolkit available here: P2-3 Facilitator toolkit: https://micksphd.flossmanuals.net/tech_appendix/00_facilitator_toolkit/00_facilitator_toolkit/ P2-3 Manual (based on use of Phaser.js) available here: https://3m-phaser.flossmanuals.net ↩︎