02. Literature Review

Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter reviews relevant literature to summarise research that supports the aims of this study. It explores several themes to establish a comprehensive understanding of the field of computer game design and programming (CGD&P). First, I summarise the findings of reviews of research on CGD&P. Given its significance in the field and practical applications, I then outline key concerns raised by constructionist researchers in their efforts to support programming education, both broadly and within CGD&P. The review then addresses pedagogical approaches relevant to the thesis’s research questions. For the purposes of this chapter, I draw on a definition of pedagogy aligned with the socio-cultural approach of this study from Siraj-Blatchford and colleagues (2002, p. 28), as a “set of instructional techniques and strategies and learning arrangements which enable learning to take place and provide opportunities for the development of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and dispositions within a particular social and material context”. I begin by examining structural pedagogies from the wider field of computer programming before focusing on those specifically addressing game making. Next, I review research on the potential and characteristics of social and cultural approaches to game making, covering topics such as pair and peer coding, coding clubs, competitions, and game jams. This section ends with an exploration of novel and robust pedagogies that enhance learner agency through initiatives such as the Fifth Dimension (5D) interventions and the Connected Learning research programme. Finally, a significant focus is placed on the use of game design patterns (GDPs), highlighting their application in computing education. By addressing these themes, the literature review positions the current study within academic discourse. Given the central rationale of the thesis, it specifically examines pedagogical approaches capable of enabling inclusive practices within game-making communities for novice coders.

A summary of research on computer game design and programming (CGD&P)

In order to provide a broad perspective on overarching concerns in this area, and to supplement the initial framing of barriers to undertaking CGD&P presented in Chapter 1, this section first examines reviews of research specifically addressing CGD&P. Several reviews explore the motivations, processes, and benefits of game development for learning (Hayes and Games, 2008; Earp, 2015; Kafai and Burke, 2015; Gee and Tran, 2016; Denner, Campe and Werner, 2019). Kafai and Burke’s (2015) review synthesises 55 relevant studies within what they term constructionist gaming, a term referring to approaches that draw on constructionist principles of learning through making and reflection within the context of digital game creation. Their analysis highlights different strands of CGD&P’s potential as well as the barriers to participation (explored in Chapter 1). The most developed section of Kafai and Burke’s review and the research from which it draws concerns how CGD&P studies address the development of personal knowledge and skills. Key topics include computer science knowledge and programming, mathematical and scientific competencies, and technical abilities that enable meaningful participation in digital culture. While social aspects such as pair programming, collaboration, self-reflection, and cultural awareness are addressed, these elements of the review are stymied somewhat, as Kafai and Burke note that many of the studies they reviewed provide little or no detail on the pedagogical frameworks guiding their interventions.

A review of CGD&P by Denner and colleagues (2019) examines CGD&P’s effectiveness in promoting computing science learning and motivation, identifying relevant subcategories of programming knowledge, problem specification, and design. Their findings are cautiously optimistic but highlight limitations in existing research, including unclear motivations driving activity, insufficient detail on the research process, and limited demographic information. Importantly, Denner et al. also note that many of the studies reviewed provide little explanation of the pedagogical methods employed, limiting insight into how learning activities were structured or supported in practice. Additionally, Denner et al. (2019), while noting these limitations, outline three emerging strands of pedagogical interest: design–build–test, step-by-step instruction, and social pedagogical approaches. These categories are useful for mapping the field, but the review stresses that they are described only in broad strokes due to limitations in the source research. As such, Denner and colleagues call for greater attention to how pedagogy is enacted and theorised within CGD&P contexts to enable more meaningful synthesis across studies.

Hayes and Games (2008), in their review, identify four main motivations for undertaking CGD&P: learning computer programming skills, deepening knowledge of other curriculum subjects, involving more girls in computer programming, and using game design to understand design concepts. Other reviews of CGD&P focus more narrowly on specific approaches or potential benefits. While Gee and Tran (2016) discuss the variety of tools available for game design, Bermingham and colleagues (2013) frame CGD&P competencies as essential twenty-first century skills, a focus echoed in a comprehensive review of digital making, which includes game development (Timotheou and Ioannou, 2019). In their review of CGD&P’s potential to encourage collaboration, Earp and colleagues (2013) found that analyses of collaboration within the design process primarily focused on peer review and other forms of feedback, leaving large gaps in understanding of the overall collaborative process.

Taken together, these reviews indicate that while CGD&P has been recognised as a promising way to learn programming and related skills, motivated by factors such as creative expression, curriculum connections, or identity exploration, barriers to participation and strategies to address them remain unevenly addressed across the literature. Some reviews focus closely on tool use and technical access (Kafai and Burke, 2015; Gee and Tran, 2016), yet there is comparatively less attention to how learning can be structured through communicable pedagogies or strategies that address barriers related to identity and culture. To address this, the present chapter undertakes a review of CGD&P research that foregrounds inclusive pedagogies aligned with the objectives of this study, namely, to understand how socio-cultural approaches can support guided participation and agency (see Chapter 1 and 3) in non-formal and community learning contexts.

Given the limitations identified above, this chapter also draws on literature on pedagogy from the broader domains of computing education and digital making. It begins with an overview of contributions from the constructionist school, which has been especially influential in shaping research on game design for learning. This overview highlights key innovations and themes that will subsequently be explored in greater depth.

An overview of constructionist approaches

The work of constructionist researchers forms an important foundation for the research landscape in both CGD&P and broader programming education. As such, many of the themes relevant to this literature review originate in constructionist research, often emerging from the activity of the MIT Media Lab (Semenov, 2017). Examples include the pioneering work of Papert (1980, 1993, 2002) on LOGO1, his innovations with programmable LEGO, and drawing turtle robot , Kafai’s (1994) early investigations into children’s game programming, and Resnick’s (2005) contributions to creative and physical computing, including the development of Scratch, a generalised multimedia authoring tool. Kafai and Burke’s (2015) framing of CGD&P as constructionist gaming underscores the continuing influence and visibility of this school of research within the field. Consequently, many researchers working in this area align their studies with constructionist principles (Harel Caperton, 2010; Repenning, Webb and Ioannidou, 2010; Weintrop et al., 2016; Kynigos and Yiannoutsou, 2018).

Despite this widespread influence, the ethos and theoretical underpinning of constructionism remain difficult to pinpoint (Laurillard, 2020). This lack of clarity may partly result from the varied interpretations of constructionism as an “epistemological paradigm, a learning theory, and a design framework” (Kynigos, 2015, p. 1). The following sections situate the concerns of this thesis within these traditions by exploring the principal strands of existing constructionist research before broadening the focus to consider its limitations and tensions.

Constructionist pedagogies: Microworlds, design principles, and resulting toolsets

Early constructionist research by Papert and Turkle (1990) notes that the dominant culture in programming education involves abstract teaching methods that alienate some learners (see Section 1.2.5). The authors describe an alternative, more tangible computing pedagogy they call bricolage, a craft-oriented approach in which participants become intimately acquainted with their tools and materials. For Papert and Turkle, bricolage approaches involve iterative experimentation, close engagement with code, clear links between function and form, and a sustained emphasis on maintaining a concrete understanding of outcomes, even when this comes at the expense of programming efficiency or code neatness. The bricolage approach forms a central tenet of constructionism and aligns particularly well with the lineage of research emerging from Papert’s involvement with the MIT Media Lab, especially work focused on tangible physical and digital artefacts designed for sharing within communities (Kafai and Resnick, 1996).

Laurillard (2020) describes a distinctive pedagogy within constructionism rooted in Papert’s vision of carefully scaffolded coding environments, or Microworlds, that support publicly shareable projects. Microworlds are simplified computational models that enable learners to explore abstract concepts, such as mathematics or physics, in a concrete and interactive way (Papert, 1980; Harel and Papert, 1991; Rieber, 2004). These environments often employ specialised, task-specific programming languages designed to reduce complexity compared to general-purpose programming languages (Guzdial, 2022). However, the integration of Microworlds within formal education settings presents challenges, as their potential can be reduced to that of instructional tools aimed narrowly at teacher-selected curricular goals (Hoyles, 1993). Papert (2002, p. 17) also warns against this institutional dilution, which he argues undermines the capacity of Microworlds to remain “exploratory, playful, [and] personally meaningful.”

Also working within the MIT Media Lab, Resnick and Rosenbaum (2013) develop a typology of constructionist design principles that support a process of designing for tinkerability2. Core characteristics include opportunities for immediate feedback, fluid experimentation, and open-ended exploration. The principle of simplifying complex or opaque processes in digital production tools to enable learners to engage quickly in creative activity is described metaphorically as having low floors. Complementary principles include high ceilings, emphasising the importance of allowing projects to grow in complexity as learners pursue more ambitious work, and wide walls, which highlight the value of supporting a diversity of media genres, project types, and approaches (Resnick and Silverman, 2005; Resnick et al., 2009).

A concern particularly relevant to this study, due to its focus on participants’ interests, is the tension between structural support or scaffolding and the principle of wide walls (Bruner, 1974). For example, the constructionist concept of the Constructopedia was developed to provide choice-based support for diverse project pathways (Papert and Resnick, 1995). A Constructopedia functions as a small-scale online encyclopedia of design elements and resources, facilitating concrete implementation while serving both as practical tools and sources of inspiration. Nichols (2007) outlines challenges associated with attempts to create resource repositories based on Constructopedia principles, including contextual limitations within certain repositories (Carbonaro, Rex and Chambers, 2004), restricted opportunities for participants to contribute their own resources, which can reduce their sense of ownership, and the overly broad scope of some repositories (Nichols, 2007).

The principles of the Constructopedia concept are partially embedded within Scratch, the MIT Media Lab’s multimedia authoring tool for novice coders. The wide walls principle is reflected in the availability of a large built-in asset library, enabling diverse project types. Additionally, all projects created within the online community can be remixed by other users. However, extracting specific features from existing projects through remixing is not straightforward, as the embedded nature of these features can make adaptation difficult (Amanullah and Bell, 2019). Together, the remixing and Constructopedia approaches highlight a persistent tension between providing inspiration and ensuring learners have sufficient technical detail to meaningfully adapt and implement features in their own projects.

Coding clubhouses and cultural programmes

Constructionist research is often conducted in community settings (Resnick and Rusk, 1996), with a notable example being the first Computer Clubhouse, an after-school club based in Boston’s Computer Museum (Resnick, Rusk and Cooke, 1998; Peppler, Chapman and Kafai, 2009). Papert (1980, p. 149), the founder of constructionism, was influenced by his observational research on community organisation within networks of Samba schools3, which he viewed as mutual learning environments that are “real, socially cohesive, and where experts and novices are all learning.” Bruckman (Bruckman, 1998, pp. 51–52) emphasises the importance of cultivating a constructionist culture to support experimental processes enabled by technological tools. Building on this idea, Bruckman and Zagal (2005) later compared the cultural learning components of a Samba school to activities within a Computer Clubhouse. To conduct this analysis, they applied socio-cultural concepts (Lave, 1991) to examine social practices such as the importance of showcase events for sharing created work, flexibility in modes of participation, and the value of diversity in participants’ skill levels and backgrounds.

MIT researcher Roque (2016) integrated family members directly into the digital making process to address barriers to computer coding as part of the Family Creative Learning (FCL) programme. FCL combines constructionist and socio-cultural ideas through a series of face-to-face sessions that use the Scratch software and playful, hands-on materials to support creative learning. Roque builds on the work of Barron and colleagues (2009) on parental roles in digital making environments to guide facilitators in helping parents and children develop their participation within community activities (Roque and Jain, 2018). Barron et al. (2009) identified social and cultural behaviours of parents in settings involving informal technology use, categorising these into specific roles, including teacher, project collaborator, learning broker, non-technical consultant, and learner. Roque’s work demonstrates the importance of exploring these collaborative roles among parents and facilitators, as well as the value of designing social, collaborative, and reflective activities to complement the more technological aspects of making. The research team produced a detailed guide to support replication of the programme (Leggett and Roque, 2017)4.

Constructionist framings of computational thinking and dimensions of fluency and agency

Constructionist research has contributed significantly to understanding computational thinking (CT) and the roles of fluency and agency within digital making. Computational thinking (CT) refers to a set of problem-solving practices associated with computing and computer science (Tedre and Denning, 2016). In Papert’s foundational work, CT was not framed as abstract problem solving, but as a way of thinking with and through computational artefacts in the process of making meaningful projects. Tedre and Denning (2016) highlight Papert’s foundational applications of CT and caution against more recent definitions that prioritise formal abstraction (Wing, 2008). Differentiating between concrete and abstract approaches is particularly valuable for examining how these contrasting perspectives shape computing education. Wing’s (2011) influential conceptualisation of CT emphasises abstraction processes and has been widely adopted within learning resources for educators (Dong et al., 2019; BBC Bitesize, no date). Her framework identifies four key pillars of CT: decomposition, pattern recognition, abstraction, and algorithmic thinking. Proponents of this approach argue that understanding these principles independently of coding contexts enhances their applicability across disciplines. This rationale has also been used by computer science educators to justify the broader integration of computing into mainstream education (Guzdial, 2008).

Building on this critique, constructionist researchers Brennan and Resnick (2012) responded to the predominantly theoretical orientation of Wing’s definition of CT (see Cuny, Snyder and Wing, 2010) by proposing a grounded, situated framework based on observations of learners designing and coding collaborative, creative projects. Their framework identifies three interrelated categories: computational concepts, computational practices, and computational perspectives. Examples include concrete code concepts (such as loops, conditionals, and sequences) and practices (such as debugging, iteration, reuse, and remixing). The broader role of community is reflected in the third category of computational perspectives, which includes expressing, which refers to creating projects that enable self-expression within a peer community; connecting, which involves engaging with others through shared computational activities; and questioning, which encourages a critical approach to technology. Lye’s extensive review of teaching computational thinking (Lye and Koh, 2014) incorporates Resnick and Brennan’s (2012) definition as its foundation, indicating the widespread use of this applied, context-driven perspective. By reconnecting with early constructionist visions of computing projects embedded within community settings, Brennan and Resnick’s framework reaffirms a grounded, flexible understanding of computational thinking as both a social and creative process (Tedre and Denning, 2016; Denning, 2017).

The applied framework developed by Resnick and Brennan builds on earlier work by Papert and Resnick (1995) on technology fluency. Fluency as an attribute appears across multiple strands of constructionist research and is described in various contexts as technical fluency (Papert and Resnick, 1995), digital fluency (Resnick et al., 2009), gaming fluency (Peppler and B. Kafai, 2009; Kafai and Peppler, 2012), and computational fluency (Resnick, 2018). The role of self-expression within fluency is also addressed by other constructionist researchers, particularly in studies of collective work in after-school computer clubs and the online Scratch community. These studies examine collective agency (Kafai and Peppler, 2008) and later collaborative agency (Kafai, Fields and Burke, 2011; Kafai et al., 2012). The researchers draw on theoretical concepts such as communities of practice (Wenger, 1998) and agency formation during collaborative knowledge production (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 1991) to explore how learners distribute responsibilities as they co-develop projects. However, within this strand of constructionist research, discussion of the process remains relatively brief, focusing mainly on online collaboration within the Scratch community rather than on face-to-face settings. Kafai’s later writing on game making (Kafai and Burke, 2015; Kafai, Burke and Steinkuehler, 2016) does not significantly expand on this promising line of inquiry into agency, an exploration that would be directly relevant to the research objectives of this thesis.

Limitations within constructionist approaches and the related field of CGD&P research

Gaps remain in constructionist research concerning explicit pedagogical approaches. Despite Kafai’s (2020; 2022) emphasis on the importance of situated and critical approaches to coding practices, several critiques of constructionism highlight a lack of clearly defined pedagogical structures within the field’s research. Vossoughi (2016) critiques constructionism from a socio-cultural and egalitarian perspective, pointing to the absence of intentional pedagogical design. Similarly, while constructionist approaches acknowledge the importance of self-expression within peer communities as an element of fluency (see above), they often lack a robust conceptual grounding. Vossoughi (2016) attributes this gap partly to an over-focus on researcher-created toolkits and communities that are orientated towards personal understandings of knowledge. When pedagogy is incorporated into recent constructionist studies, it typically appears as broad design principles or general project-based learning strategies (Resnick, 2012, 2017). A later section of this chapter examines these principles in greater depth. It seems likely that these deficits arise more from omission than intentional design, given the similar critiques made by constructionist researchers themselves, who caution against overly technical approaches and toolsets at the expense of expressive potential within community settings (Resnick, 2020; Resnick and Rusk, 2020). Kafai and Burke have likewise called for further research into the social and cultural dimensions of game making. The gaps within CGD&P research, an area strongly shaped by constructionist thinking, may therefore reflect limitations both in analytical scope and in the theoretical models employed by constructionist researchers.

In line with the primary research question, which examines how CGD&P research can be enriched through socio-cultural approaches, the next section explores a range of pedagogies that offer insights relevant to this inquiry.

Pedagogies to support game making via coding

Following the focus of the research objectives on developing a new pedagogy to address gaps in existing research and practice concerning CGD&P, this section explores existing pedagogical approaches applicable to this domain. Given the gaps identified in current CGD&P research, the discussion also draws on broader literature from computing education and digital making. While the forthcoming sections touch on areas similar to those highlighted by Denner and colleagues (2019), including design–build–test approaches, stepwise or instructional models, and social pedagogical strategies, these do not map directly onto the structure of this review. The design–build–test category corresponds closely with project-based learning approaches, which are examined in greater depth, as they align with the methodology and aims of this research and offer the most detailed treatment of pedagogical structuring concepts. Denner and colleagues also note that information about pedagogy across studies is often sporadic and inconsistently reported, limiting the precision of these categories. For this reason, the following sections use their framework as a flexible reference point for developing a more applied understanding of pedagogical approaches relevant to game making through coding.

Explicit teaching: Step-by-step instruction and principles-first teaching of computational thinking

In Denner et al.’s (2019) review of CGD&P, stepwise learning approaches were observed in 40 out of 68 studies. Stepwise approaches, as identified in the review (Denner, Campe and Werner, 2019), refer to both step-by-step/linear instructions for students to follow, and incremental project challenges which increase in difficulty or scope. I explore the former here using the term step-by-step to differentiate. Within step-by-step instruction or tutorials, educators typically guide learners in using tools to achieve pre-set goals, embedding underlying principles of computational thinking and concepts within this instruction so that learners absorb them through active engagement.

An alternative instructional strategy is the principles-first approach (Repenning et al., 2015), informed by Wing’s (2008) advocacy for explicit teaching of decomposition, pattern recognition, abstraction, and algorithmic thinking. Given the abstract nature of computational thinking (CT) principles, this approach applies to varied domains of coding. Wing’s perspective on computational thinking, being more theoretical than applied, invites discussion on effective methods for delivering principles-first approaches. Grover (2013, 2017) and Guzdial (2015) outline explicit techniques that leverage computer programming as a mechanism for teaching CT principles. Bell and colleagues (2019) investigate unplugged activities, which introduce abstract CT concepts without using computers or coding. Other research examines challenges in teaching computational thinking principles within non-computing disciplines (Dong et al., 2019).

The remit of this literature review does not extend to a full critique of the validity of Wing’s strand of computational thinking within computer science or other disciplines5. However, while a principles-first approach, which emphasises understanding foundational concepts before practice, may appear logical, it can exacerbate foundational barriers to participation when learners encounter complex, abstract material (Papert and Turkle, 1990) (see also Section 1.2.5). Consequently, the following sections prioritise pedagogical practices that lead with or integrate concrete exploration of coding processes. ### Design frameworks using stages & project-based learning (PBL)

As identified by the systematic review of CGD&P (Denner, Campe and Werner, 2019), the design–build–test pedagogy is common in this field, appearing in 30 out of 68 studies. The review illustrates the design–build–test approach using the Globaloria programme, which structured project work around an iterative cycle of design stages, namely: Play, Plan, Prototype, Program, and Publish. The approach is iterative in that the final stage of publishing a game invites further play, and thus re-evaluation of the design, and subsequently another iteration of the design process. Many similar frameworks exist in diverse areas of production, including computer science (Pereira and Russo, 2018), engineering (Wi̇Narno et al., 2020), design processes (Dam, 2024), and project-based learning.

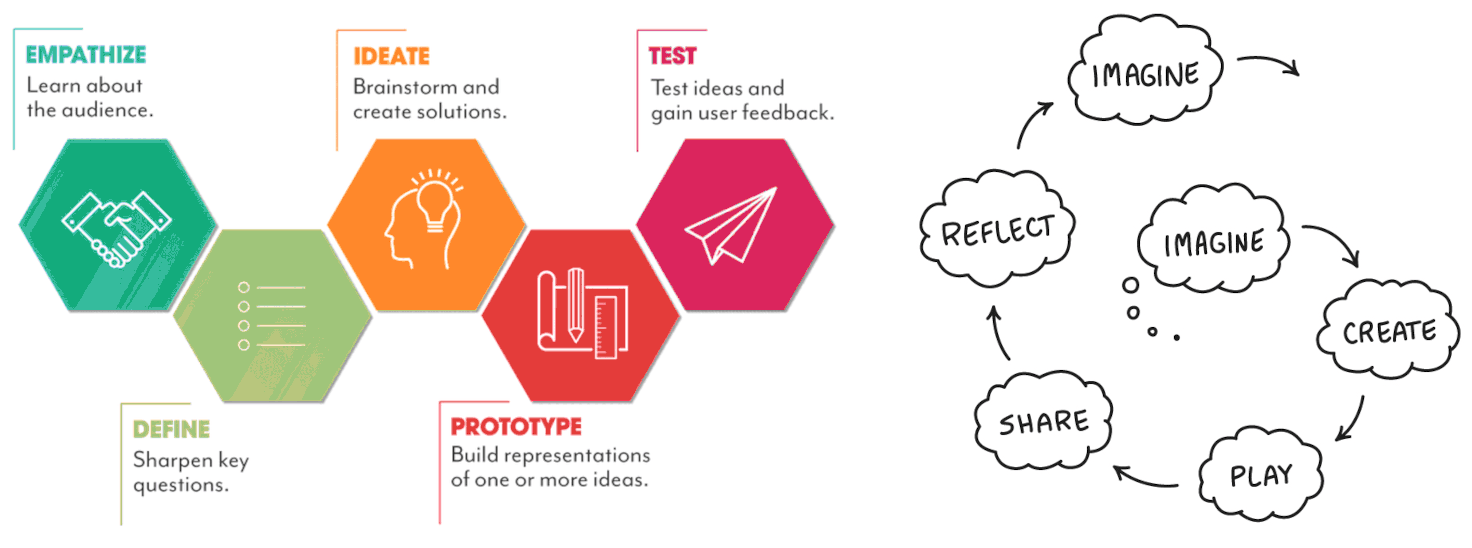

Addressing the domain of design thinking, Figure 2.1 includes a graphical representation of design thinking stages from the Institute of Design at Stanford (Dam, 2024). The stages can be described in the following way: Empathise – learn about the audience; Define – sharpen key questions; Ideate – brainstorm and create solutions; Prototype – build representations of one or more ideas; Test – test ideas and gain user feedback.

Similarly, to illustrate the iterative nature and importance of community in design approaches to making, Resnick advocates the use of a creative learning cycle model for educators, shown in Figure 2.1 (Resnick, 2017). The five circular stages are Imagine, Create, Play, Share, and Reflect, followed by a return to Imagine. Within the context of computing education, Resnick (2012) describes the foundations of design-based approaches in education as engaging in design activities, exploring personally meaningful topics, collaborating with others, and deepening understanding through reflection. While research on the use of design thinking in education is broadly supportive, identifying potential to develop creative planning and collaborative skills (Lor, 2017; Luka, 2019), there are limitations within the field of design thinking and education, including a lack of clarity in terminology, limited guidance on implementing design stages, and vague theoretical justification of the overall process (Micheli et al., 2019). To address these limitations, this review turns to the field of project-based learning, which shares the stage-based characteristics of design thinking but has been more explicitly developed and analysed within socially constructed theories of learning (see Chapter 3).

The field of project-based learning (PBL) encompasses a wide range of educational research exploring pedagogical approaches that align with the socio-cultural focus of this thesis. PBL approaches also incorporate an iterative design model (Jia, Jalaludin and Rasul, 2023), and existing research provides detailed analyses of the processes and rationale involved at each stage. Broadly defined, PBL is an educational strategy that advocates learner autonomy in project selection, which can enhance motivation (Darling-Hammond et al., 2008); authentic and shareable project outcomes, supported by learning environments that encourage peer feedback and reflection (Hung and Wong, 2000; Gibbes and Carson, 2014); iterative project work, which supports mastery; and challenging goals with structured scaffolding, enabling learners to persist and succeed in complex tasks (Blumenfeld et al., 1991).

Significant challenges exist in applying PBL, including practical constraints such as timetabling and time pressures within formal settings (Marx et al., 1997), restricted access to authentic resources (Thomas, 2000), and variations in facilitator expertise and confidence (Ertmer and Glazewski, 2015). One of the core difficulties for educators arises from the shift in perspective required to move from a traditional teacher-led model, where subject knowledge is directly delivered, to a facilitative role that enables learners to take greater ownership of their activities. Perhaps because of its emphasis on active knowledge construction rather than instruction-heavy teaching (Kokotsaki, Menzies and Wiggins, 2016), PBL is sometimes misinterpreted as an unstructured, pure discovery approach (Kirschner, Sweller and Clark, 2006). However, while no single framework for scaffolding exists, contextually relevant support remains an essential component of PBL (Hmelo-Silver, Duncan and Chinn, 2007).

In a STEM learning context, Pitot and colleagues (2024) analyse a widely recognised project design rubric developed by PBL Works6, which emphasises the development of complex project challenges, sustained inquiry, authentic engagement with tools, student agency, critique and revision, reflective learning, and publicly shareable outputs. Ertmer and Glazewski (2015) present a similar categorisation, highlighting the importance of group work facilitation, structured opportunities for reflection, and discipline-based argumentation, in which project work helps learners explore subject-specific knowledge frameworks. Ertmer and Simons (2005) emphasise the value of differentiating scaffolding strategies to support teachers in delivering PBL effectively. Saye and Brush (2002) distinguish between hard and soft scaffolding, where hard scaffolding provides structured, static support for planning and content organisation, while soft scaffolding involves dynamic, relational strategies such as responsive questioning and collaborative problem-solving.

Ertmer and Glazewski (2015, p. 97) identify a persistent tension in PBL design related to scaffolding, namely balancing the benefits of student autonomy, which sustains engagement, with the practical need to restrict participant choice so that facilitators can provide adequate support without becoming overwhelmed. Leat (2017), in his analysis of school-based PBL through a socio-cultural lens, emphasises the importance of integrating what Moll (1992) describes as funds of knowledge, resources that learners draw upon in both formal and informal settings7. However, implementing such resources can present challenges for teachers, who may lack familiarity with the communities in which their students participate (González, Moll and Amanti, 2007). Leat (2017) suggests that activity theory provides a valuable socio-cultural framework for examining these tensions within ecological learning environments.

Project-based learning frequently presents students with challenges framed as wicked problems, which require ongoing reassessment and adaptation to identify contextually appropriate solutions (Kłeczek, Hajdas and Wrona, 2020). Similarly, the challenge of designing effective scaffolding for PBL also meets the criteria of a wicked problem, requiring educators to adopt flexible, evolving strategies to accommodate emerging technologies and shifting learning contexts. Although the broader principles of project-based learning contribute valuable insights, literature addressing scaffolding specific to CGD&P remains limited, constrained not only by acknowledged gaps in CGD&P research addressing socio-cultural perspectives (Kafai and Burke, 2015) but also by the inherently dynamic nature of the field.

Some studies have explored how general PBL structures and iterative design stages can be applied to game making, demonstrating their alignment with project-based learning approaches and their role in providing structural support (Kafai and Burke, 2015; Denner, Campe and Werner, 2019). Simmons and colleagues (2012) describe a five-stage design process that helps students plan and manage their game projects, illustrating how PBL principles can be concretely adapted to creative computing contexts. Although Pitot and colleagues’ (2024) work is situated within a broader STEM education framework rather than game making specifically, it remains relevant because it demonstrates how PBL rubrics can scaffold complex, authentic projects and help support agency. Taken together, these studies suggest that the structural logic of PBL can inform and strengthen pedagogical approaches to game making by providing adaptable frameworks that support creativity, collaboration, and the exploration of underlying concepts.

Similarly, researchers studying the Globaloria programme (Reynolds and Chiu, 2013) found that the intrinsic motivation associated with game making encouraged sustained engagement, increasing the likelihood that participants would refine, test, and revise their creations in line with PBL pedagogy. However, many studies cited by Denner and colleagues (2019) as examples of the design–build–test approach lack detailed accounts of students’ design processes or fail to communicate scaffolding strategies for teachers and facilitators (Wang and Chen, 2010, 2011; Robertson, 2013; Ke, 2014). While publication constraints may explain some omissions, they also appear to reflect genuine gaps in the research. For instance, the online supporting materials for the Adventure Author project by Robertson (2013) focus primarily on software usability rather than providing structured guidance on the design process.

Design-stage and project-based approaches align closely with this thesis’s focus on authentic, iterative learning, yet their limited treatment of scaffolding in CGD&P contexts within the published literature reveals a broader gap in how such strategies are shared and developed. While general PBL structures offer a valuable foundation, they do not fully account for the distinctive challenges of game making as a socio-technical learning activity. As a result, more targeted scaffolding approaches that address the specific opportunities and complexities of CGD&P are required and are examined in the following sections.

Use-Modify-Create (UMC) and half-baked games

The Use-Modify-Create (UMC) approach proposed by Lee and colleagues (2011) offers a promising strategy for reducing user anxiety and demotivation linked to the complexity of coding games. UMC originates from research on undertaking game making as a vehicle to enhancing computational thinking (Denner, Werner and Ortiz, 2012; Werner et al., 2013; Denner et al., 2014; Werner, Denner and Campe, 2014). The UMC model advocates remixing existing games as a scaffold for developing novice coders’ competence. Learners are guided to make progressively complex modifications, thereby becoming increasingly proficient in recognising and applying computational concepts and structures (2011). In the Use stage, learners familiarise themselves with coding interfaces, code structures, and syntax. In the Modify stage, they engage with pre-existing projects, deepening their understanding of coding concepts and practices by adjusting the code to meet their own aims. In the Create stage, after developing familiarity with code design patterns introduced during the Modify phase, learners reproduce and adapt these patterns in independently created projects.

UMC enhances engagement by lowering technical barriers to participation and strengthening learners’ sense of ownership by allowing greater choice in defining project outcomes. A study involving five hundred 9-to-14 year-olds found that the UMC approach successfully balances structured learning with opportunities for student-led exploration (Franklin et al., 2020). Researchers also observed that students valued the flexibility, choice, and sense of agency engendered by the model. Additional research comparing UMC with a starting-from-scratch approach found higher levels of student engagement in the UMC group (Lytle, Catete, et al., 2019), as learners spent more time actively manipulating code and incorporating personal touches that enhanced their sense of ownership over projects. These findings align with constructionist research highlighting the motivational potential of enabling learners to design and publicly share code-based products (Kafai and Resnick, 1996). However, increased choice can also introduce two key challenges. First, students may diverge from intended subject areas, and second, facilitators may experience stress when managing diverse, open-ended activities. Noss and Hoyles (1992) describe the first issue, where greater freedom can lead to off-topic engagement, as the play paradox. To address the second challenge, Lytle and colleagues (2019) propose replacing the open-ended Create phase with structured extension options, shifting the emphasis from Create to Choose. This modification allows facilitators to anticipate learner pathways and prepare more targeted forms of support.

Half-baked games, proposed by Kynigos and colleagues (2007; 2018), are intentionally unfinished or contain deliberate deficiencies intended to motivate learners to modify the design or code and improve the game. The concept builds upon Papert’s work on Microworlds (1980; 1991). Like Microworlds, half-baked games encourage flexible adaptation in directions that interest the learner (Kynigos and Yiannoutsou, 2018), while ensuring the learning process remains educationally productive. To achieve this, the creator of the half-baked game makes design decisions that emphasise specific features of the game and the underlying code, encouraging learners to explore fundamental computational concepts. Kynigos and Yiannoutsou (2018, p. 2) conducted a study that provided “tools affording them (13–15 year olds) the role of game hackers,” allowing them to alter existing game code. The researchers identified progression in coding complexity among learners throughout the intervention, beginning with pattern recognition associated with reading code and advancing to more sophisticated practices, including abstraction, structural organisation, and sequencing of their own algorithms. In earlier work, Kynigos (2007, p. 336) described the potential for half-baked artefacts to encourage learner dialogue around coding challenges, framing them as “a communicational tool to shape a common language within the community,” thereby highlighting their alignment with social and cultural pedagogical approaches.

Use Modify Create (UMC) and half-baked games provide structured pathways into CGD&P by lowering entry barriers and encouraging learners to extend existing designs. These approaches align with the principle of guided participation, supporting learners to build confidence through gradual involvement in design practices. However, while they enable progression from simple modifications toward more complex creation, they often lack clear guidance on how learners’ contributions can be sustained or shared. This highlights the need for approaches within CGD&P that make scaffolding processes more visible and enduring, a focus taken up in the following sections.

Levels of abstraction, semantic profiles & PRIMM

The work of Sentance and Waite (2021), culminating in a recent report on teaching strategies within UK computing education, identifies a range of relevant pedagogical approaches, including levels of abstraction and semantic profiles. The concept of levels of abstraction (LOA) supports both teachers and students in developing a hierarchical understanding of coding processes (Statter and Armoni, 2016; Waite et al., 2016; Waite et al., 2018). While abstraction is a concept interpreted in diverse ways within computer science (Hazzan, 2002), in this context it refers to a continuum between overarching concepts and concrete implementations, as illustrated in Table 2.1.

| Level | Focus | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Level | Thinking about the problem without programming | Task - what is needed |

| Design Level | Structuring / designing a solution | What it should do. |

| Code Level | Writing the actual code | How it is done |

| Execution Level | Understanding how the computer processes the code on a low-level (e.g memory use), or in a k5 context the outputs | What it does. |

Table. 2.1 Breakdown of levels of abstraction. (Waite et al., 2018)

Guided by research highlighting the potential efficacy of abstraction in supporting programming practices (Cutts et al., 2012; Statter and Armoni, 2016), Waite and colleagues (2016) examined the relevance of abstraction awareness for primary school-aged learners. While the process initially lacked a structured pedagogy, the authors identified potential in learners’ ability to move between levels as a form of self-regulation. In particular, activity at the design level enabled novice coders to make realistic judgments about code implementation in relation to their time constraints and developing abilities (Waite et al., 2018).

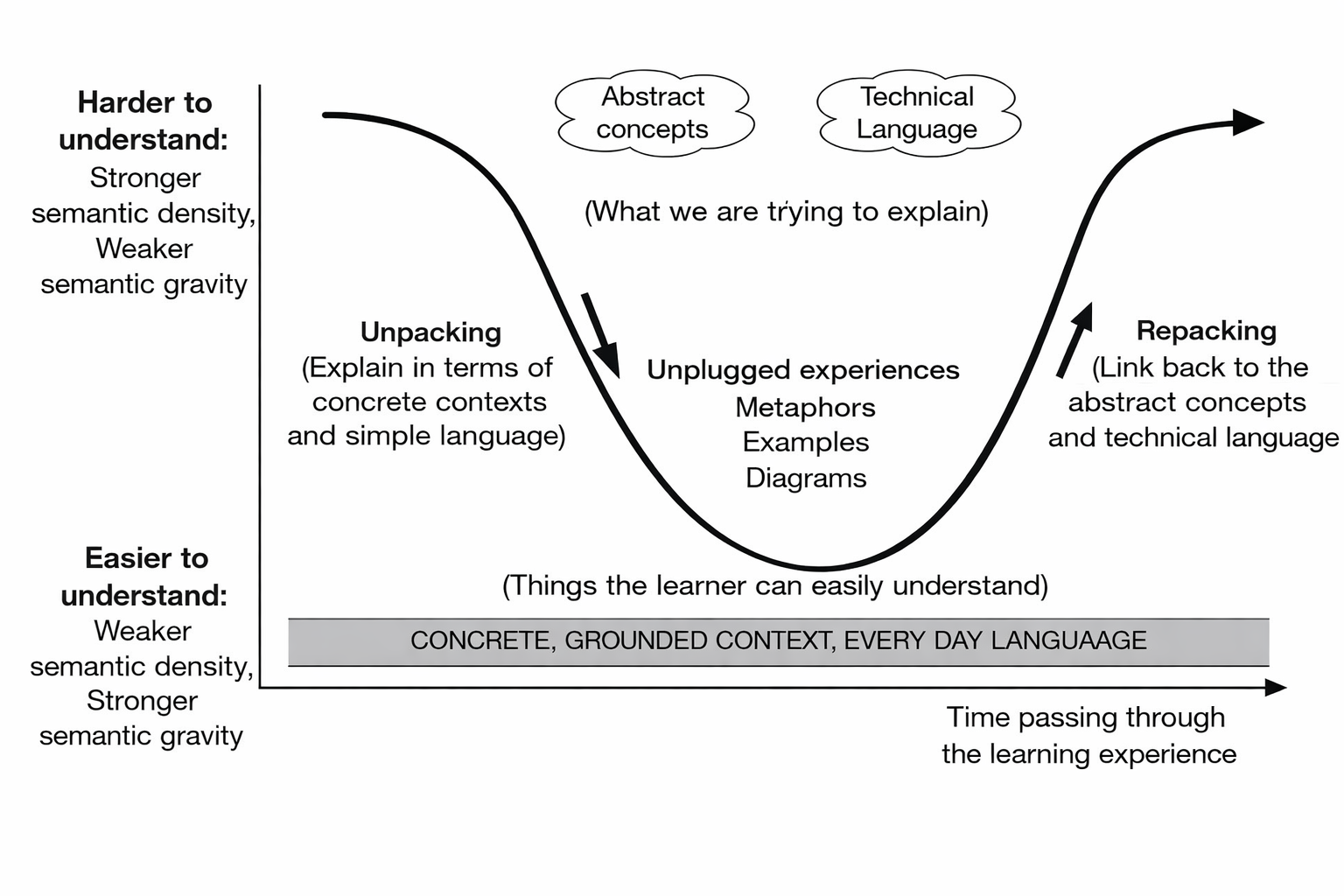

Semantic profiles illustrate the use of more concrete (high semantic gravity) language and more abstract (high semantic density) concepts and patterns as they evolve in classroom discourse (Macnaught et al., 2013). Research conducted by Curzon and colleagues (2020) within computing education demonstrates the benefits of wave-shaped semantic profiles over flatlines, which remain either overly tied to concrete examples or detached within abstraction (see Figure 2.2 for an example). Building on this work, the authors advocate a process of unpacking, exploring, and repacking ideas throughout a lesson, allowing learners’ understanding to deepen as concepts are applied in practice and reconnected to abstract principles.

Later work by Waite and Sentance (2017) builds on the ethos underlying UMC, LOA, and semantic profiles to develop an applied pedagogy for computing education known as PRIMM. The motivation behind PRIMM is to address the tension between exploration-based learning approaches and those that advocate greater structure and guidance (Sentance, Waite and Kallia, 2019). The approach also responds to calls for computing education to align more closely with socio-cultural perspectives (Tenenberg and Knobelsdorf, 2014), drawing on the concepts of mediation and the zone of proximal development (ZPD) (Sentance, Waite and Kallia, 2019). PRIMM (Predict, Run, Investigate, Modify, and Make) expands upon the UMC model by introducing additional learning stages. Learners are first encouraged to predict the outcome of a given code example before running it to test their understanding. Through guided exploration, they then investigate possible code modifications before proceeding to modify the provided code themselves. The final Make stage, which corresponds to the Create phase in the UMC model, supports students in developing complete programs or constructing larger components of code independently.

The adoption and discussion of PRIMM in UK school contexts has grown significantly in recent years (Martin et al., 2020; Parry, 2020; Ofsted, 2022), likely due to its practical applicability in classroom settings and its inclusion in pedagogical frameworks promoted by the National Centre for Computing Education (NCCE) through computing pedagogy resources (NCCE, 2020). However, while PRIMM and LOA pedagogies are not inherently limited to formal schooling, there is currently little or no research exploring their implementation in non-school or informal learning environments. Sentance and colleagues (2019) acknowledge further limitations, proposing that future research should explore co-production possibilities for differentiation in collaboration with teachers, framed within socio-cultural approaches. They also recommend stronger alignment between session planning informed by LOA concepts and lesson delivery incorporating the PRIMM framework.

Approaches such as levels of abstraction, semantic profiles, and PRIMM provide valuable insights into how learners can progress from surface-level manipulation toward deeper conceptual understanding in computing. These frameworks emphasise the sequencing of activities and the transitions between concrete and abstract representations, making them especially relevant to the barriers discussed in Chapter 1. However, while they offer powerful analytical tools, their application within CGD&P remains limited. In the context of this thesis, these approaches are significant not only for highlighting learners experience of moving between abstract concepts and concrete design actions, but also as analytical tools with which to examine the development of participant agency within CGD&P. This theme will be revisited in Chapter 7, where the implications for sustaining participation and supporting learner diverse trajectories are explored in detail.

Use of design patterns

Research Question 2 of this study asks how gameplay design patterns (GDPs) can act as conceptual and social scaffolds in CGD&P. This section reviews the role of design patterns in education and design communities more broadly, introduces readers to underlying concepts, and considers their relevance to game making. Design patterns offer structured solutions to recurring design challenges, illustrated through concrete examples of design principles in context (Alexander, 1977). Documenting and sharing design patterns supports the development of design communities, scaffolding collaborative problem-solving and innovation. The use of design patterns, which originated in the field of architecture (Alexander, 1977), has been widely applied in computer programming and software design (Gamma et al., 1995). In higher education, a design pattern approach is frequently used to teach object-oriented computing, by modelling community-based design decisions (Fojtik, 2014). This helps to break down complex problems, making them more modular and concrete (Muller, Haberman and Averbuch, 2004; Waite and Sentance, 2021). While the modular nature of the knowledge generated supports both replicability and generalisation in research, Dearden and Finlay (2006, p. 20) advise careful consideration when defining the scope of pattern formulation, noting that patterns that are too abstract may be impractical for real design use, while overly specific patterns may be difficult to adapt to new scenarios. Similarly, Eriksson et al. (2019) expand upon the work of Höök and Löwgren (2012) to position design patterns in games as a form of intermediate-level knowledge, bridging the detailed implementation of specific elements with broader theoretical concepts.

The use of design patterns has been widely adopted by game designers and educators working with games in varied ways (Björk and Holopainen, 2005). In the professional context of game programming, collections of structural game design patterns serve to share coding practices and establish a common language of game design (Björk and Holopainen, 2006). The term game design patterns (GDP) is applied in different ways, with Kreimeier (2002) distinguishing between content patterns and structural software engineering patterns . Content patterns describe recurring design elements that are visible to the end user. Building on the work of Bergström et al. (2010), this study adopts the term GDP to refer specifically to gameplay design patterns, a content related subset of game design patterns orientated towards game elements that end players can recognise or directly experience.

Collections of such gameplay design patterns have been used as tools in research, helping researchers to design and analyse activity and to engage novices in game design processes. In an educational intervention working with 11- to-12 year-olds, Eriksson and colleagues (2019) applied a curated selection of patterns to guide learners in analysing and proposing modifications to an existing collaborative game, Stringforce. The study incorporated learner-led game analysis, level design adjustments via a graphical (non-code-based) editor, and co-design of conceptual changes to existing games. Their research built upon a collection of over 200 GDPs, developed in a related research project aimed at supporting novice adult game designers, available as a public resource (Björk and Holopainen, 2005). The structuring of these patterns drew from broader game theory principles, particularly the MDA framework, which categorises GDPs into game mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics (Bergström, Björk and Lundgren, 2010). Game mechanics refer to the rules and systems that govern gameplay, game dynamics describe emergent behaviours resulting from these mechanics in player interaction, and game aesthetics invoke emotional responses through gameplay elements such as graphics, story, and sound design.

The process of curating patterns for Stringforce involved selecting only 14 from the full collection (Eriksson et al., 2019). The criteria for choosing patterns to include in the co-design stages considered several factors. Concrete patterns were prioritised over more abstract ones to support learner comprehension, selected patterns aligned with the learners’ capabilities, and patterns related to game mechanics were favoured, along with those suggested by the learners. The Stringforce study highlighted several aspects of GDP utility. GDP concepts functioned as a common language between researchers and participants, helped structure the analytical framing of the research process, and served as reference points for participants’ design proposals (2019). Overall, the findings primarily emphasise benefits for researchers, advancing GDPs as a form of intermediate knowledge that contributes to the field of child-computer interaction (CCI) research. As the potential of GDPs to act as scaffolds for learner-led project work remains underexplored, the following section details the use of GDPs oriented towards that purpose within two research projects.

Game Star Mechanic and Scalable Game Design

This section examines Game Star Mechanic and Scalable Game Design, two well-documented educational programmes that incorporate gameplay design patterns (GDPs). Game Star Mechanic (GSM) is an online platform whose design is rooted in socio-cultural perspectives on learning and is intended to explore and develop systems thinking, design thinking, and media literacy using games as multimodal texts (Salen, 2007). In GSM, video game creation uses a simplified block-based system to modify existing games, eliminating the need for programming (Games and Squire, 2008). The design choices within GSM were informed by research highlighting the advantages of using games over other forms of media projects, particularly their interactivity and rules-based structures, which support the exploration of systems thinking and design approaches (Torres, 2009; Games, 2010; Tekinbaş et al., 2014).

The pedagogy embedded in GSM software draws on game theory developed by the Institute of Play founders (Salen, 2007). The guiding pedagogy is reflected in an extensive support pack for teachers8, which incorporates themed challenges focused on categorising key game elements, specifically space, components, mechanics, goals, and rules. In evaluative reviews, Games (2008; 2010) explores how the design of GSM enables learners to leverage their prior knowledge of game design patterns in ways that support complex collaborative design and discourse among novice designers. Games also examines the role of community aspects within the pedagogy, showing how these elements help participants develop an awareness of audience and engage in active critical roles within a design community (Gee, 2004).

Scalable Game Design (SGD) is a computing education programme developed and delivered by the University of Colorado, which, like GSM, created a software tool called AgentSheets to facilitate game creation, accompanied by supporting teaching resources and training. AgentSheets uses a block-based, drag-and-drop programming approach. Extensive partnership work led by Repenning and Basawapatna (2010; 2010) enabled large-scale data collection from thousands of school students. The researchers use the term computational thinking patterns to describe patterns present in computer games that support learners in their coding. The familiarity and clear applicability of these patterns to specific learning outcomes guided SGD researchers towards this pattern-based approach, rather than more abstract interpretations of computational thinking. Their interactions with teachers also shaped decisions to highlight concepts with applications in science simulations (Basawapatna et al., 2011). The authors provide examples of computational thinking patterns, such as generation and absorption in predator–prey relationships.

In SGD research, a concept of proximal flow is advanced, linking flow theory9 with the importance of engagement through scaffolding that maintains learners within a zone of proximal development (ZPD)10, and emphasising the social and environmental nature of that support (Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi, 2009; Basawapatna et al., 2013). This proximal flow theory informed the structuring of tutorials within the programme (Basawapatna, Repenning and Savignano, 2019). The concept of just-in-time instruction, providing learners with information or guidance at the point it is needed, aims to reduce boredom and increase engagement by closely linking instructional support to immediate, tangible game-related goals.

Another important factor within SGD pedagogy is student ownership, particularly participants’ ability to design their own characters and backgrounds (Repenning et al., 2015). However, the strongly scaffolded approach, requiring step-by-step instructions due to the complexity of the game authoring process (Repenning et al., 2015), created restrictions on students’ overall autonomy. While the authors of the SGD programme recommend allowing students to create their own games, this is presented as an optional activity at the end of a unit, which many schools could not implement due to time constraints. This may explain the relatively low figures for student ownership, with only 139 out of 700 responses (20 percent) indicating aspects of student ownership (Repenning et al., 2015). Other limitations include the programme’s reliance on bespoke software developed by the team, which raises concerns about long-term maintenance. Additionally, while the resources are described as just-in-time instruction, a review of the supporting website reveals lengthy step-by-step instructional materials. As the just-in-time concept is driven by learner choice, extended reliance on such materials risks undermining this intended experience. As such, there appears to be a disconnection between the researchers’ aims and the resulting materials.

Taken together, Game Star Mechanic and Scalable Game Design demonstrate the potential of pattern-based approaches to support novice designers by making recurring elements of games visible and learnable. Both embed pedagogical strategies that resonate with this study’s objectives. GSM does so through its emphasis on community, collaboration, and learner discourse related to created games. SGD does so through its articulation of proximal flow and just-in-time scaffolding. At the same time, their limitations, including restricted learner ownership, reliance on bespoke tools, and the persistence of step-by-step instruction, highlight the need for approaches that can sustainably connect patterns, pedagogy, and participation in flexible ways. This thesis develops these techniques within its applied pedagogy through an exploration of how gameplay design patterns can be mobilised to develop agency and inclusive participation in non-formal CGD&P contexts.

Social approaches and cultural programmes

Building on the previous review sections that addressed structural pedagogies, this section turns to approaches that emphasise the social and cultural dimensions of learning in CGD&P. Denner and colleagues (2019) identify social interaction as the third major pedagogical strand in their review of CGD&P, observed in 35 of the 68 studies examined. Their analysis, similar to Earp’s (2015) earlier work, highlights limitations in the scope of social and collaborative interventions, which were largely confined to pair programming and general feedback mechanisms applied to game projects. To address these gaps, the following sections first examine research that explicitly analyses collaboration within CGD&P, particularly studies on pair programming and peer learning. The discussion then broadens to consider cultural programmes that situate game making within community and family learning contexts. Together, these perspectives provide insight into how collaboration, participation, and identity formation can be supported through more inclusive and socially grounded pedagogies.

Pair programming and collaborative approaches

Pair programming is a widely used industry practice that has also been integrated into educational contexts (Hanks et al., 2011). It involves pairing students together and assigning them two distinct coding roles that are periodically alternated. One student actively codes, while the other focuses on the overall design and logic of the programme. A key advantage of pair programming is its ability to build coding confidence, as students gain experience in both roles. To support novice coders, teachers should model and break down coding processes to improve accessibility. Werner and colleagues (2007; 2009) examine this approach as a strategy to address gender disparities, extending research on collaborative problem-solving in computer programming. They cite studies challenging the gendered dichotomy between bricolage and abstract problem-solving, but highlight the need for further exploration of programming styles and strategies (Denner and Werner, 2007). Their research suggests that while pair programming is broadly beneficial, it is particularly effective in narrowing participation gaps related to gender and socio-economic background (Werner and Denning, 2009, p. 31). In Denner and Werner’s research, pair programming incorporates social learning elements, providing students with greater autonomy in problem-solving strategies and opportunities to construct their identities as programmers.

Beyond the specific technique of pair programming, the process of building an identity within a coding community, facilitated through the broader principle of peer collaboration, is central to a socio-cultural understanding of how learners develop programming skills in both classroom and non-formal settings. The value of peer approaches is not confined to pair work and can extend to collaborative groups of larger sizes. For example, the work of Werner and Denner (2009) builds upon existing research into collaborative social reality and joint problem-solving spaces, using these frameworks to scaffold the process of ideation (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995). Additionally, the role of friendly relations is identified as a factor in creating productive, ongoing interactions in peer learning processes (McDowell et al., 2006). Waite and Sentance (2021) examine the potential for peer instruction in computing education, both as a distinct pedagogy11 and as a broader collaborative approach to learning programming.

Popat and Starkey (2019) highlight that collaboration and the sharing of code as ways of supporting peers often emerge organically rather than as deliberately planned aspects of learning designs. Earp and colleagues (2013) point to a surprising gap in studies investigating collaboration as both a learning process and an outcome, despite the diverse roles involved in game making being well suited to such activity. These gaps are particularly striking given that the development of learner identity within a collaborative culture is widely recognised as fundamental to exploratory, project-based approaches that underpin the research objectives of this study (Kolodner et al., 2003). Taking a broader perspective, the following sections therefore examine how several relevant cultural programmes have sought to address these challenges, and the extent to which they offer strategies for more inclusive participation in CGD&P.

Game competitions and coding clubs

Coding clubs have been discussed above in relation to the constructionist strand of research, drawing on the early legacy of Computer Clubhouse initiatives (Peppler, Chapman and Kafai, 2009). In a UK context, despite extensive volunteer-led activity, research remains limited on three closely related coding club projects: Code Club, CoderDojo, and Raspberry Jams. Existing research covers various aspects, including the use of Code Club resources by volunteers (Aivaloglou and Hermans, 2019), general facilitation approaches, and the absence of an overarching conceptual model at CoderDojos (Alsheaibi, Huggard and Strong, 2020). One strategy identified to focus participant activities is the encouragement of competition entries in computing and engineering fields (Aivaloglou and Hermans, 2019).

Since 2010, a variety of coordinated online CGD&P competitions have been organised by entrepreneurial organisations such as the Globey Award from Globaloria, as well as by foundations and public bodies, including Games for Change and the STEM Video Game Design Challenge, the latter sponsored by the White House in the US (Kafai and Burke, 2013). Game projects also play a significant role in the Collab Challenge, an initiative within the Scratch online community (Kafai et al., 2011; Kafai et al., 2014). In the UK, the Coolest Projects competition operates in partnership with CoderDojos and Code Clubs.

Research by Quinlan and colleagues (2018; 2020) examines Coolest Projects, identifying key themes from interviews with participants. The study reveals diverse entry points for project engagement, with some students initially drawn to technology, others motivated by a specific idea or problem, and some focused on developing particular skills. The authors also highlight the broader benefits of such competitions, echoing findings from wider research, including the inspirational and motivational impact of seeing peers’ work (Kafai, Burke and Mote, 2012; Kafai et al., 2014), the development of confidence across multiple areas, the enhancement of teamwork and collaborative problem-solving skills, and the significant role of adults in facilitating connections to professional communities and providing logistical support, including parental involvement (Quinlan and Flóriánová, 2018). This final consideration informs critiques of competition models concerning inequality of access, as not all parents are able to provide this level of support for their children (Thumlert, de Castell and Jenson, 2018). Further concerns arise from the largely uncritical embrace within these competitions of the values associated with computing industry (Thumlert, de Castell and Jenson, 2018), a challenge also noted within the broader maker movement (Vossoughi, Hooper and Escudé, 2016).

Coding clubs and competitions highlight both the promise and the limits of community-based initiatives in CGD&P. They have the potential to motivate engagement and collaboration and can serve to connect young people to professional communities, yet they also risk reproducing inequalities of access. These tensions reinforce the importance of examining socio-cultural approaches that foreground inclusivity and sustained participation, a focus of the following sections.

Educational game jams

A game jam is an event and process characterised by an accelerated production method, group collaboration, and an ethos of innovation (Gabler et al., 2005; Arya et al., 2013). In game jams, participants create games in teams (or sometimes individually) within a time-constrained period, typically 24 or 48 hours. While the premise of game jams is to promote collaboration, often involving creative constraints related to the subject of the games to be created12, events are inconsistent in their support for and scaffolding of collaborative approaches (Goddard, Byrne and Mueller, 2014). Team events often take place in physical venues and may be part of wider global jams (Arya et al., 2013). Meriläinen (2019) notes the potential of game jams but also the lack of research on the learning mechanisms at play in jam events. Aurava and colleagues (2021) build on this work by exploring the use of game jams in formal education contexts, confirming their inherent potential while also noting the need for external tutoring and links with existing game jam communities. Arya and colleagues (2019) identify limitations of the Global Game Jam in terms of youth participation and outline the development of the more supported approach of Global Game Jam Next (GGJN), a youth programme launched in 2018 targeting the next generation of game designers and providing free access to game making resources.

The educational resources provided by GGJN are shaped by the educational process developed within a prior programme named the Moveable Game Jam (MGJ) (Games for Change, 2017), which was created by a collective of New York educators and educational foundations. The MGJ game jam guide employs playful methods to enhance inclusivity in the process. To address concerns about inclusivity in adult game jams, various format adaptations have been made. MGJ can be implemented within a shorter timeframe, emphasises low-cost approaches, and supports both digital and analogue offline game production. It features loosely structured activities and broad goals, allowing for significant learner agency. The MGJ process communicates fundamental concepts of game design, particularly through a simplified analysis of game elements, an approach adopted by other game jams and competitions13 (Games for Change, 2017). Similarly, other key techniques incorporated into later game jam programmes include the use of non-digital games, periodic facilitation, extensive peer testing of games (known as playtesting), adopting playful roles within game creation, and engagement with professional game designers and communities (Kultima, Fowler and Khosmood, 2023; Kultima, Koskinen and Nummenmaa, 2024).

Kultima and colleagues (2024) examine the challenges of game jam processes, even with adaptations designed for educational settings. These include the importance of careful planning and clear expectations to align the experiences of novice and more experienced game designers, as well as the difficulties of time management in more formal learning environments. Additionally, Eberhardt (2016, p. 3) identifies tensions related to the commercialisation of game jams through commercial sponsorship and the promotion of a “game developer lifestyle” over the educational benefits involved.

In summary, while research on game jams in educational contexts explores their pedagogical potential, including elements of social capacity building, tangible outcomes, engagement, play, and soft skills, much of the current literature remains focused on feasibility and practical implementation rather than offering a detailed examination of pedagogical processes. An exception to this trend is the Moveable Game Jam (MGJ), which introduced a playful exploration of game elements directly relevant to the contributions of this study (see Chapters 5 and 6).

Fifth Dimension interventions & Connected Learning approaches

While this chapter has explored various promising pedagogies and studies aimed at enhancing CGD&P, a common limitation identified across these approaches is the lack of alignment with theoretical perspectives that address social and cultural aspects of learning. Many of the initiatives discussed, including game jams, coding clubs, and competition-based models, are under-theorised. They tend to focus on practice and participation rather than providing a clear account of how learning and identity formation are supported or explained. Even where there are broad influences from constructionist thinking, explicit theoretical grounding is often limited, with researchers placing greater emphasis on practical outcomes or tool design. A few programmes, such as Game Star Mechanic and Scalable Game Design, make use of theoretical ideas like systems thinking, flow theory, and scaffolding, but these remain exceptions rather than the norm. This section therefore marks a shift towards the focus of the next chapter, which examines theoretical frameworks in more depth. It introduces a different strand of work that explicitly aims to theorise learning through a socio-cultural lens. This includes a series of educational partnerships known as The Fifth Dimension (5D), which were implemented in technology-rich, non-formal settings, often within after-school clubs in lower-income communities (Cole and Packer, 2016). 5D interventions were designed with a primary research objective of developing socio-cultural understandings of learning processes. Initial iterations, led by Michael Cole at San Diego University, were supported by the University’s provision of volunteers, equipment, and technical assistance to design and deliver a creative series of computer-based, playful activities in the local community. Cole (2009) describes two contextual motivations behind the design of 5D: the need for accessible after-school programmes, and the opportunity to provide undergraduate students with practical experience, helping them connect their academic understanding of child development with real-world applications.

The use of novel computer communication technologies such as games and email served a dual purpose, providing opportunities to address reading deficits (Cole, 2009; Cole, Packer and Kobelt, 2014) and countering the potential alienation of women and girls from STEM subjects (Cole and Griffin, 1987). 5D researchers examined the resulting programme as a collaborative initiative, designed to facilitate a joint learning experience between participants and volunteers, each with shared but distinct objectives. The intervention integrated a fictional narrative involving a wizard, with whom young participants engaged via email, motivating them to participate in both digital and play-based activities that simultaneously developed their written and computer literacy skills (Brown and Cole, 2008). The long-term nature of the project led to regular young attendees mentoring new cohorts of student volunteers, supporting their understanding of both the technical and social dynamics of the programme. This process helped young participants develop a sense of expertise, while providing student mentors with valuable insights into the mutual learning processes involved (Cole, 2009).

The importance of designing interventions to support the formation of participants’ identities within the evolving cultures of learning sites became a central aspect of ongoing research (Cole and Griffin, 1987). Varied cultural practices emerged across different settings, responding to the interests and needs of specific learning environments (Cole and Engeström, 2007). This capacity for adaptation was significant because it demonstrated how learning cultures could be co-constructed through the interaction of local practices, tools, and community values, rather than imposed through a fixed curriculum. This strand of research into culture formation was further developed by Kris Gutiérrez, who led two 5D interventions, Las Redes (Scott Nixon and Gutiérrez, 2012) and El Pueblo Mágico (Gutiérrez et al., 2019). In both sites, researchers examined the value of a multi-lingual cultural environment in shaping site-specific learning cultures. In related work, Gutiérrez and Digiacomo (2008; 2017) identify the crucial role of learning designers in facilitating identity transitions between different settings, using responsive learning design that enables learners to draw upon funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1992; Moll, 1998). Gutiérrez and colleagues (2019) also clarified an implicit design motivation underlying previous 5D interventions, noting that the experience should be enjoyable for young people. Fun was essential not only to maintain engagement, but also to enable greater expressions of competence and agency, allowing learners to draw upon their prior experience of play across different contexts. Gutiérrez (2014; 2020) developed the concept of horizontal movement of practice between sites of learning, in contrast to a vertical, top-down transmission model (see Chapter 3). The role of identity development in socio-cultural and technical learning environments is explored further in the findings chapters.

Some of the ideas developed within the 5D programme were further expanded through their incorporation into an approach called connected learning, part of a project to which Gutiérrez contributed, the Connected Learning Research Network (CLRN) (Ito et al., 2013). CLRN examined education for the digital age, drawing on the foundational ethnographic work of Gee and Ito discussed in Chapter 1. It proposed specific principles to guide a broader model of connected learning, focusing on movement between digital and non-digital learning spaces. These principles included ensuring that learning is socially embedded (through peers and communities), interest-driven, and oriented toward opportunity (such as pathways to educational advancement, career success, and civic engagement). The project advocated for expanding access to digital media-related learning opportunities, particularly for under-served youth. This research, through case studies, reports on pedagogical strategies, and approaches to leveraging digital media, has made a valuable and influential contribution to the field. However, while this body of work includes one case study examining game design using a non-coding tool (GSM detailed above) (Rafalow and Salen, 2014), it does not provide specific guidance on how to operationalise the broader principles of connected learning as a distinct pedagogy for supporting CGD&P in formal or non-formal settings. Thus, while the 5D and Connected Learning case studies provide valuable illustrations of how socio-cultural design can link learning to community practice and personal interests, the lack of concrete application within CGD&P highlights a need for further research to develop domain-specific pedagogies aligned with these guiding strategies. This focus on bridging theory and practice through socio-cultural design principles also anticipates the direction of the following chapter, which outlines the theoretical framework underpinning this study.

Concluding section

Chapter 1 outlined the study’s key needs, framing the problem through barriers to participation, including technical challenges, guided pedagogies, and cultural factors. This chapter has reviewed existing pedagogical approaches in CGD&P and digital making more broadly, while also identifying gaps that remain under-explored. Before revisiting the research questions, it is useful to summarise the key gaps highlighted across this review. Step-by-step and principles-first approaches provide structure but overlook how participation is scaffolded. Design-stage and project-based learning emphasise authenticity but lack detailed application to CGD&P. Use-Modify-Create and half-baked games lower entry barriers but offer few strategies for sustaining contributions. Levels of abstraction and semantic profiles support conceptual movement yet remain underused in game making. Large-scale programmes such as Game Star Mechanic and Scalable Game Design show the value of pattern-based approaches but depend on bespoke tools and limited learner ownership, signalling a need for more flexible and socio-cultural scaffolding.

In relation to RQ114, the research gaps in structural and technical approaches indicate that, while various game making tools exist, there has been limited exploration of authentic tool usage and community engagement. My focus on a toolset comprising a code playground and a professional JavaScript game library (see Glossary) presents an opportunity for further investigation. Similarly, while UMC (Lee et al., 2011), half-baked games (Kynigos and Yiannoutsou, 2018), and PRIMM (Sentance and Waite, 2017) demonstrate potential, this study develops these ideas further by integrating socio-cultural pedagogies drawn from the Connected Learning and 5D programmes. Additionally, as few CGD&P studies provide sufficient pedagogical detail to support replication, this study contributes by documenting learning processes and publishing materials for facilitators as open educational resources (OERs).