01. Introduction

Introduction

Introduction to the thesis

This study examines the creation of interactive, online media through the production of web-browser-based games for educational purposes. Digital technology is increasingly providing diverse opportunities in the fields of work, education, and home life for those with access to it. These opportunities are balanced with potential costs at both a societal and individual level. Over the lifespan of this thesis, there have been significant developments in narratives concerning digital media and participation within online communities. At the start of my work in this area in the early 2010s, concerns about a deficit in computer literacy and digital skills within the workforce were prevalent, particularly regarding the lack of computer programming skills (Livingstone and Hope, 2011). Despite this concern, at that time, the overall tenor of the underlying narrative concerning young people and technology was generally optimistic. While challenges existed in ensuring equal opportunities for access, new technologies were providing diverse opportunities for learners both within the classroom and in future fields of employment, for example through the expansion of creative coding initiatives, school programming curricula, and participatory online platforms supporting remixing and peer learning (Resnick et al., 2009; Ito et al., 2013). By way of contrast, current narratives surrounding the impact of generative artificial intelligence (AI) and commercially driven social media on young people are less optimistic. Specific concerns include the risk that the convenience and automation of tasks in the form of generative AI and related software services may diminish critical thinking skills, making individuals overly reliant on technology (Gerlich, 2025); the emergence of sophisticated media production and delivery systems which, driven by algorithmically generated suggestions, can lead to passive consumption of media and amplify divisions within society (Ruckenstein, 2023); and the negative effects of increased screen time on young people and the resulting reduction in real-life interactions (Livingstone and Blum-Ross, 2020). Young people’s participation in social media and online gaming highlights tensions between opportunities for self-expression and the risks associated with the development of self-identity. An example of such a risk is that these digital environments often create insulated communities that separate young people’s experiences from real-life contexts, leaving parents either unaware of the risks involved or aware but excluded from their children’s online worlds (Avci, Baams and Kretschmer, 2025).

In response to the risks above, there are increasing calls for young people and families to engage in forms of digital resistance, often taking the form of reduced participation in online communities or limited consumption of digital media from corporate sources (Syvertsen and Enli, 2020; Kuntsman and Miyake, 2022). For example, a total boycott of services like Facebook, TikTok, and Instagram has been proposed by some commentators. However, for young people with their working lives ahead of them, such an abstinence from commercial digital participation may prove limiting and even alienating. Furthermore, given that digital non-participation may remove some critical voices from important debates on our shared futures, a more tactical and selective approach may be more productive, both on an individual level and for society. An alternative strategy is to support young people to develop a more active and critical engagement with media production. A diverse set of stakeholders, including educators (Resnick and Rusk, 2020), cultural commentators (Rushkoff, 2010), and media theorists (Itō et al., 2010), have advocated for a broader approach to digital education that includes media literacy and hands-on coding experiences through creative digital projects, a call which remains relevant today. The unifying ethos is that, to benefit from the expressive and empowering potential offered by digital media products such as websites, games, videos, music, and podcasts, learners should be able to write as well as read digital formats (Resnick, 2002; Lessig, 2009).

This thesis reports on research that brings families together in a new learning environment to learn how to create video games inspired by early arcade and platform games. As such, this work addresses diverse elements, including the development of skills needed to participate in computer game design and programming (CGD&P), a term used throughout this thesis to describe creative learning activities that combine coding, design, and playtesting of digital games (Denner, Campe and Werner, 2019). It also explores the process of self-expression and identity development within an emerging community, and the possibilities for structuring the learning experience to help overcome inherent barriers to participation. This chapter provides an overview of the context, rationale, process, objectives, and significance of this study. While the setting of this study is non-formal in nature, CGD&P is present and relevant in both formal and non-formal computing education contexts, and the following section therefore outlines the changing contextual features of each. Following this, I outline key barriers to participation in game making. The rationale driving this work is then presented, connecting my personal context with broader motivations. The final sections of this chapter briefly address the theoretical framework, research questions, research objectives, and the potential significance of the thesis.

Context and background of the study

This section begins with an exploration of key contextual factors. The immediate context of the core activities of this research comprised a new learning community made up of home-educating families attending a series of game making sessions held on my university campus. Sessions involved families, myself (as both a researcher and teaching facilitator), and, for most sessions, volunteer university student helpers. The section situates the research within a set of key contextual themes. It begins with the context of non-formal, home-education settings, before addressing digital making as a broader educational activity in both formal and informal contexts, and then focusing on CGD&P as a subset of digital making. The section concludes by exploring barriers to participation within this domain.

Non-formal and home education contexts

The setting of this research within a non-formal activity attended by families requires clarification at this stage. The nature of formality in learning is examined briefly here using two dimensions: setting and educational structure. Formal education is understood here as learning characterised by institutionally prescribed curricula, timetables, and assessment structures. While definitions of informal education are complex, the term generally refers to learning that occurs outside the traditional school environment (Sefton-Green and Erstad, 2012). However, as Sefton-Green (2006) notes, formally structured learning can take place in informal settings, and vice versa. Other writers (Eshach, 2007, p. 173; Werquin, 2009) use the term non-formal to describe learning that happens with less direct instruction than a typical classroom experience but which still comprises an organised learning experience, existing between formal and informal learning on a spectrum. This study uses the term non-formal in this way, while informal is used more loosely to indicate activities happening outside a classroom context. This research, while taking place in the formal location of a university campus, can be viewed as a non-formal form of activity, drawing on the experiences of participants gained through informal learning in game-playing activities.

To aid the reader in interpreting the findings, this section examines the context of home-educating families and the circumstances shaping the participants’ engagement in the study. The processes and motivations driving home education are varied (Fensham-Smith, 2021). These motivations are often categorised into two broad streams: ideological and pedagogical (Galen and Pitman, 1991; Rothermel, 2003). From an ideological perspective, some families choose home education to limit their children’s exposure to mainstream values, such as religious beliefs or consumerist ideals. From a pedagogical perspective, popular concepts within home-education circles include unschooling and deschooling. Holt’s concept of unschooling (Gray and Riley, 2013) emphasises facilitating learning by drawing out children’s interests through everyday activities. Illich’s work (1971) on deschooling promotes the idea of webs of learning, where learners access educational experiences in varied contexts based on their interests and needs rather than relying on a single educational institution as the sole source of knowledge. Many home-educating families actively seek and establish networks, using friendships, social networking groups, and email lists to share opportunities and collaborate on learning activities (Doroudi and Ahmad, 2023). The game making club that forms the basis of this research can be viewed as one node within the complex web of learning in which participating families engage.

In addition to concerns of pedagogy and ideology, an increasingly relevant strand of motivation for families to home educate relates to challenges surrounding inclusion and support for diverse learners within mainstream educational provision (O’Hagan, Bond and Hebron, 2021). Some parents withdraw their children from school due to a judgement that schools are unable to meet their children’s particular educational needs. This is particularly the case for less visible disabilities such as dyslexia, ADHD, and autism (Connolly, Constable and Mullally, 2023). In a review of the experiences of parents who home educate children with autism, motivations for withdrawal from school included the exclusionary nature of mainstream schooling, a lack of teacher knowledge, and the subsequent absence of inclusive educational practices (O’Hagan, Bond and Hebron, 2021).

Context of digital making

The process of digital game making is located within a wider setting of digital making and its associated culture. Gee (2004) describes the process of learning in informal environments and the resulting opportunities for participants to follow their own interests and to group together with others who share similar aims, framing these communities as affinity spaces. Gee’s research (2004) on young people’s participation and learning in digital and online communities, in part, addresses the domain of computer games. He describes the activity and culture created around the process of playing games as meta-gaming. Examples of meta-gaming include fan websites and fiction, the sharing of tips, and the creation of imitation games or related artwork. Gee’s work, in particular, examines how shared discourses and emerging identities develop within these spaces. Similarly, Ito’s (2009; 2010) ethnographic studies of informal digital consumption and making in the home chart the progression of young makers of digital products within online communities. Her approach connects the opportunities of new online tools with a sociocultural view of learning as embedded within social and cultural contexts (Ito et al., 2013). Sefton-Green (2013) also explores salient themes in digital making, including its alignment with valued digital skills required by the workforce, anxieties around young people’s use of digital technology, and the value of diverse learning settings. Sefton-Green notes, however, a persistent gap in research examining how learning opportunities and learner trajectories transfer between informal experiences, formal education, and professional destinations, a gap that remains significant more than a decade later.

Observations of young people’s enthusiastic involvement in digital making, media, game making, and meta-gaming in informal communities have sparked questions about how to leverage this interest as a foundation for other educational aims (Papert, 1980; Gee, 2004). This underlying question partly informs the ethos of this thesis, aligning with my experience as described later in Section 1.3.3. Digital making is itself a subset of a long tradition within education known as the maker movement, whose underlying ethos can be described as a complex mix of practitioner enthusiasm, industry participation, and progressive educational approaches (Blikstein, 2018). The recent reduction in cost and technical barriers to hardware tools such as 3D printers and microcontrollers, along with software provided by free and open-source software (FLOSS, see Glossary), have contributed to their widespread adoption by enthusiasts at home and, increasingly, in education. The engagement of many teachers and volunteers in these initiatives is evident in the proliferation of articles, videos, blog posts, and other resources sharing novel practice. This groundswell of activity is also visible in community events with multi-generational audiences, such as the annual Liverpool MakeFest and the numerous monthly Raspberry Jam events held in different regions across the UK (Shea, 2019). These grassroots educational technology events bring together teachers, professionals, young people, and their families to engage with the diverse technologies listed above in playful, empowering, and technically challenging ways.

Advances in web technology have brought new possibilities for online digital making accessed through the internet browser. In early 2013, MIT released a new version of their educational Scratch software, a coding tool for beginners. This introduced new features through an online editor, including the default ability to save projects online, making them accessible in different locations. The ability to comment on and remix projects1 led to a significant increase in both the volume and forms of community interaction. For more advanced learners, free web-based courses on authentic, text-based programming languages such as Python and JavaScript added interactive elements to online coding tools, helping to scaffold and motivate the acquisition of coding concepts and practical coding skills. A Mozilla white paper (2014) outlines the power of exploring web technology as an empowering activity. As part of their Teach the Web and Web Literacy programmes, Mozilla created internet browser-based tools to support novices to investigate, remix, and create their own pages within simple browser interfaces. One tool of particular significance was Thimble (now deprecated), a code playground (see Glossary) (Queirós, Pinto and Terroso, 2021), which allowed scaffolded use of web technologies and provided a social platform and community for publishing web page projects. The Thimble website became a hub for online activity taking place within localised Mozilla Webmaker Clubs. Important features of these Webmaker Clubs included activities drawing on home interests to encourage creation and sharing of projects, and the exploration of digital literacy elements needed to be an effective citizen (Thorne, 2015). In 2015, I contributed an online course called Quacking JavaScript to the Webmaker curriculum. In my report on its underlying pedagogical approaches (Chesterman, 2015), I outlined several possibilities to increase participant engagement, including playful approaches, the use of games, and enabling participants to incorporate popular culture and home interests into their work. I also noted the challenges of applying an experimental, exploratory approach within the confines of a school setting.

This overview of digital making highlights how creativity, play, and participation have long intersected with technical skill development in informal learning spaces. What stands out across these initiatives is their combination of accessibility, social motivation, and self-directed exploration, qualities that this thesis later re-examines in relation to computer game design and programming. The community-based and remix-enabled practices described here also foreshadow the ethos and design principles explored in later chapters, where digital making becomes a focus for inclusion, collaboration, and the development of participant agency. My own work is situated within, and contributes to, this tradition, and as such this thesis communicates important practical detail concerning the technical and cultural aspects of digital making. Examining these details shows how the interrelationship between tools, settings, and community dynamics shapes learning opportunities, and how inclusive practices can be deliberately designed within community-based digital education.

Context of formal computing education

While this study is based in a non-formal context, its findings are relevant to the wider landscape of computing education, where similar debates about creativity, inclusion, and digital literacy continue to shape policy and practice. The changing shape of computing and digital-focused education in UK schools can be examined through several key developments. The first is Google’s then-CEO Eric Schmidt’s speech (2011, p. 8) at the MacTaggart Lecture in Edinburgh, in which he criticised computing provision in schools: “Your IT (information technology) curriculum focuses on teaching how to use software, but gives no insight into how it’s made.” The second was the Royal Society report Shut Down or Restart? (The Royal Society, 2012), released in early 2012. The report recommended steering the UK information and communication technology (ICT) curriculum towards computer science and programming, providing funding for professional development, improving inclusivity in computing education, and increasing partnership work with computing professionals. In the same week, Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove (2012) announced the planned scrapping of the ICT curriculum. Finally, a new computing curriculum was introduced in 2013 to a mixed response (Department for Education, 2013). While community responses were collected through consultation, a clear consensus to retain digital literacy and creative project work was largely ignored in the final curriculum (Twining, 2013). Preston (2013) shares Twining’s view that Gove and Schmidt’s critique of earlier ICT provision was misjudged, arguing that ICT had been caught up in decisions that were more political than pedagogical in nature, particularly in aligning with a discourse advanced by the technology sector. These shifts illustrate how computing education policy in the UK has tended to prioritise technical skill and industry alignment over creative or participatory digital practices, thereby creating a context in which alternative, community-based approaches like those explored in this study have the potential to offer valuable insight.

A recent report by Kemp and colleagues (2024) on the future of computing education echoes concerns raised earlier in the After the Reboot report (Waite, 2017) about the 2013 computing curriculum and related exams. Both reviews highlight unequal participation, with girls, ethnic minorities, and students from lower socio-economic backgrounds less likely to take computing qualifications, often due not only to general preference, but also to cultural barriers, subject difficulty, or restricted access to digital subjects. After the Reboot also identified areas of promise that remain relevant to this study, including the potential of game making to increase engagement, the use of design patterns to scaffold coding, and a greater focus on social and cultural aspects of coding. Kemp and colleagues (2024) build on these recommendations by emphasising the importance of informal digital making and project work involving inclusive approaches to coding. Yet, despite this advocacy, the structural limitations of the curriculum and examinations persist. These challenges underline a continuing mismatch between opportunities provided by digital making and the restrictive nature of formal computing provision in the UK. As a result, many practitioners and researchers have turned to lunchtime or after-school coding clubs, community initiatives, and informal spaces where creative forms of game making can be explored without the constraints of the national curriculum. This shift highlights the significance of non-formal learning environments as sites for innovation, inclusion, and the development of new pedagogical approaches in computing education. This study responds to these gaps and argues that non-formal activities within formal settings should be explored further, given the initiative and apparent success of educators working at the classroom level.

Computer game design and programming (CGD&P) as a subset of digital making

In this thesis, I explore CGD&P and participation in coding community practices by home-educating families. This section begins by outlining broad contextual motivations for undertaking CGD&P, then briefly describes the context of gaming culture within families before providing a fuller summary of potential barriers to undertaking CGD&P. While much research on CGD&P focuses on its educational benefits for subjects such as mathematics, science, and computer science, particularly through programming (Kafai and Burke, 2015), other research addresses diverse motivations driving game making. These include supporting a STEM pipeline into industry (Holmes and Beeck, 2023; Edwards et al., 2023), developing communication, creativity, and digital literacy, often framed broadly as 21st-century skills (Robertson and Nicholson, 2007; Bermingham et al., 2013), and exploring social and ethical issues (Peppler, Danish and Phelps, 2013). An underlying theme in many of these motivations, and one prevalent in advocacy for CGD&P, concerns the expressive potential of digital media (Resnick, 2018). For Resnick (2017), developing fluency, whether in writing prose or computer programming, involves cultivating thinking, voice, and identity. A fuller exploration of computational fluency and the wider concept of agency is undertaken in Chapters 2 and 3.

Turning to family learning settings, the wider context of game playing is relevant. While both adult and child novice game makers have the potential to draw on their game playing experience in their creations, their experiences may vary widely. Game playing practices and the opportunities provided by participation in wider communities continue to evolve, shifting from a marginal activity to a more established place within mainstream culture (Engelstätter and Ward, 2022). For example, casual and retro games played by both adults and children are increasingly available via smartphones and home consoles (Juul, 2012). Additionally, increasing numbers of parents are gamers or have past gaming experience (Engelstätter and Ward, 2022). This experience is sometimes drawn upon when parents work with their children to regulate gaming activities. Studies of parental mediation of children’s gaming identify varied strategies, including restrictive mediation involving limiting access, active mediation through discussion and negotiation, and co-playing of games as a form of mediation (Nikken and Jansz, 2006; Eklund and Helmersson Bergmark, 2013). Understanding these modes of parental mediation is relevant to this study because they may inform how families negotiate access, autonomy, and support in creative activities such as CGD&P.

Some classic or retro games have achieved cult status, reflected in recent blockbuster films featuring Mario, Pac-Man, and Sonic the Hedgehog. Nostalgia surrounding such games and their continued presence in youth culture create opportunities for connection between younger and older players (Boyle and Kao, 2017). Thus, the process of making retro games with families lies at a confluence of diverse contexts, motivations, and possibilities. The sustained popularity of retro games, combined with easy-to-use game making tools and code frameworks designed to facilitate such games, provides an entry point for game players into game making cultures, a trend reflected in the popularity of projects based on retro games on game publishing websites that allow amateurs to share their self-made games (Garda, 2014)2. However, while these contexts and related processes offer opportunities for educators to leverage participant interest and experience to motivate and facilitate the learning experience, there are also significant barriers to participation, which are explored in the following section.

CGD&P inherits some of the intrinsic difficulties associated with computer programming (Gomes and Mendes, 2007; Sentance, Waite and Kallia, 2019; João et al., 2019). These difficulties include the complexity of programming language syntax, the challenge of understanding abstract concepts, and problems with transferring skills between different contexts (Gomes and Mendes, 2007; Rahmat et al., 2012). To address these issues, specialist coding tools have been developed for novice coders, and in particular for younger audiences. These tools aim to simplify coding syntax, project organisation, and the overall complexity of the coding environment (Yu and Roque, 2018). However, this simplification creates a tension between using more authentic programming languages and tools and relying on scaffolded, specialised approaches (João et al., 2019). Sefton-Green (2013) explores this tension in the context of digital making, contrasting Mozilla Webmaker tools, which use web languages like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, with simplified systems like Scratch, which can distance learners from authentic programming languages. These tensions have also been examined at an epistemological level. Papert and Turkle (1990, p. 134) identify exclusionary potential in the dominant formal, abstract approach to computer programming that “emphasizes control through structure and planning”. They characterise this abstract approach as including a top-down design process involving extensive planning prior to coding, explicit teaching of language principles and syntax, and coding from scratch rather than altering existing products. Papert’s (1980) foundational work in programming education addressed these barriers through the inclusive design of both tools and learning environments, for example LOGO, a simplified programming language.

Difficulties in structuring and accessing learning experiences in informal and collaborative settings present another significant barrier to CGD&P participation. For instance, a key review highlights the limited availability of specific pedagogical approaches for social engagement in CGD&P (Kafai and Burke, 2015). While Chapter 2 will explore existing approaches in detail, it is useful here to illustrate the inherent challenges through an example, namely the educational practice of tinkering, used as a way of structuring creative work. Tinkering, in this context, refers to a hands-on, learner-led interaction with materials or digital artefacts, where learners try things out, make small adjustments, and immediately see the results (Vossoughi and Bevan, 2015). For example, this might involve adjusting a block of game code to see if a character moves differently. The learner adapts familiar concepts and processes to new situations, much like the improvisational approach of a skilled artisan (Papert, 1993, p. 143). Bevan and Petrich (2014) have shown how tacit practices can be made explicit in museum-based physics tinkering. However, applying similar approaches to game making presents particular problems. While such open-ended and exploratory methods can drive engagement (Sheridan et al., 2014), they can also make it harder for learners to complete projects in the form of playable games, particularly if they lack access to examples, problem-solving guidance, or the resources needed to realise their own ideas (Bevan, Petrich and Wilkinson, 2014). Rogoff’s work (2016) highlights a further dimension of this problem. Rogoff (1995, p. 211) rejects the simple division between child-led exploration and adult-led instruction, instead proposing a community-based model of guided participation that blends autonomy with scaffolded involvement from more experienced others (Rogoff, 1994). This distinction highlights a further barrier: although guided participation is recognised as valuable within sociocultural understandings of learning, strategies for enacting it in game making remain seldom documented. Because guided participation processes are complex and context-dependent, they can be difficult to communicate in ways that practitioners can readily adopt. Challenges therefore exist in relation to dissemination, especially for educators who are less familiar with these approaches. These challenges raise questions about the sustainability of such practices beyond the specific contexts in which they first emerge. The concept of guided participation, and how it relates to other dimensions of learning in a community, is explored in more detail in Chapter 3.

Inequality of access to digital making communities and practices presents another significant barrier. Historically, the lack of access to necessary technology, such as high-cost computers, constituted a major issue (Resnick and Rusk, 1996). While lower equipment costs and the equipping of school and community venues with computers and internet access have addressed some of these concerns, technological access represents only one dimension of the problem. Sefton-Green (2013) suggests that even with improved access to equipment, many young people still face barriers to meaningful participation in online digital communities. Even among those who participate in such communities, creative activities that result in finished digital products are uncommon, with studies such as Luther et al. (2010) revealing an approximately 80 per cent failure rate in collaborative media projects within the online community studied. Sefton-Green (2013) therefore argues that motivated and capable facilitators are essential for supporting sustained participation. In addition, the appeal of online digital making communities, as described by Ito and Gee (2004; 2010), is inconsistent due to cultural barriers and varying levels of inclusion.

Beyond questions of access and participation, barriers linked to identity and values represent a further challenge. A key claim within CGD&P research concerns the potential for games to increase participation by young people traditionally excluded from computing and digital making cultures (Kafai and Burke, 2014). However, the picture within wider research is not clear-cut. While digital making can provide diverse opportunities for some learners, Vossoughi et al. (2016) critique the underlying culture of digital making, highlighting the need to integrate the values and cultural experiences of working-class students and students of colour into the making process. Other researchers also identify political concerns associated with the close alignment of maker culture and makerspaces with the STEM industry (Vossoughi, Hooper and Escudé, 2016; Thumlert, de Castell and Jenson, 2018). Vossoughi et al. (2016) caution against approaches and environments that implicitly promote the idea that digital making is primarily a pathway to joining the computer programming industry through the development of employability skills in young people. Thumlert and colleagues (2018, p. 4) argue against the ongoing appropriation of skills such as creativity and design thinking, which they suggest are increasingly co-opted by market-driven agendas rather than used for critical and emancipatory purposes. The authors also warn that this positioning could lead to a return to instruction-based models narrowly focused on curricular outcomes, rather than enabling the development of learners’ expressive capacity within a community (Thumlert, de Castell and Jenson, 2018).

Cultural aspects related to gaming provide both opportunities and potential barriers to participation in CGD&P. While the widespread appeal of casual and retro gaming, alongside the proliferation of retro games in popular culture, offers a rich repository of knowledge that can be utilised in various educational contexts (Moje et al., 2004), Kafai and Burke (2017) balance this potential with the complex issues of gender representation associated with gaming culture. Addressing gender-based barriers to participation, Papert and Turkle (1990) identified how some girls become alienated from abstract computing approaches. They emphasised the need for diverse teaching and learning styles to address issues surrounding the early socialisation of women and girls, advocating for the inclusion of personal and concrete working styles. Denner and colleagues (2008; 2014) demonstrated that inclusive gender practice in game making involves allowing participants to choose both the content of their games and the dominant mode of play, that is, game mechanics, within them. Their findings present a nuanced view of girls’ interests in game genres and support research cautioning against gender stereotyping and rigid identities in this area (Pelletier, 2008). Kafai and Burke (2014) address gender identities within game design by advocating for the creation of new communities and learning environments that align with participants’ values, rather than attempting to draw girls into existing male-dominated spaces. Similarly, Buechley et al. (2008, p. 431) ask, “How can we integrate computer science with activities and communities that girls and women are already engaged in?”

Margolis et al. (2008) outlined barriers contributing to a racial gap in computing participation and achievement in the US, including feelings of isolation, limited access to computing opportunities, and a lack of social support. DiSalvo and colleagues (2008; 2009; 2014) investigated these barriers within a game testers programme, examining how an interest in computer games could motivate access to computing education. Their findings indicated that activities should not only be engaging but also align with the underlying values of the programme’s young African American male participants.

This section has outlined diverse and relevant contexts for the study, including informal and home-education settings, digital making practices, and school-based computing education. Within this landscape, CGD&P appears as a distinctive subset of digital making, offering rich opportunities for creative exploration but also characterised by barriers to wider participation, such as access to resources, confidence, and inclusive pathways. These contextual strands frame the rationale for the study, which the following section introduces in relation to the study’s research focus and questions.

Rationale for the Study:

Personal context

The use of technology for self-expression explored in this thesis reflects my personal and professional trajectory. My journey within the world of technology and education began in the 1990s through my participation in organising and promoting unlicensed music events, free festivals, and related campaigning activity. Within the party and protest culture that emerged from the 1994 campaign against the Criminal Justice Bill (McKay, 1998), email lists and websites became important outreach and organising tools. I was an enthusiastic early adopter of these technologies as tools for social change. In the 2000s, my focus shifted towards environmental activism, migrant rights, and left-libertarian activities challenging the unaccountability of international financial institutions such as the World Bank. Self-made media and related cultural activity formed an important part of this movement. The advent of relatively affordable Hi8 and later MiniDV domestic camcorders, along with PC-based editing software, helped to reduce the financial and technical barriers to video production. In 2000, I began work with Undercurrents, a video activism magazine (Heritage, 2008), where I ran their website and began digitising VHS content for online distribution. My role also involved organising film screenings and music events for outreach. This work culminated in my involvement with a broad network of media and internet activists associated with the Indymedia project (Pickard, 2006). Indymedia was a volunteer-run coalition of media activists that used non-hierarchical volunteer organising to enable a federated system of open-publishing news websites spanning hundreds of cities and regions.

These decentralised organising and production principles, important to both non-hierarchical protest movements and FLOSS communities, also began to impact broader participatory digital culture. In particular, the repurposable nature of digital content and alternative approaches to attribution, beyond the restrictions of the copyright system, gave rise to widespread remixing as a creative process (Lessig, 2009). Lessig (2004) describes the possibilities of this technological trajectory and the resulting activity using the term free culture. In 2011, I co-authored An Open Web 3, a book that celebrated the opportunities provided by open-source and decentralised web technologies to create a more egalitarian environment for digital participation and, importantly, also noted emerging risks to this mode of engagement. Around this time, I shared relevant approaches with local organisations by providing internet and media creation training and community development support in Manchester and Salford. I also undertook writing, and later organisational work, with an organisation called FLOSS Manuals, where I developed documentation and online learning resources for media creation and collaborative processes aimed at individuals and informal educators.

Discussion around the launch of the new UK computing curriculum in 2013 championed the possibilities of creative digital production within the classroom (Livingstone and Hope, 2011). In that year, I undertook a Master’s in Computing, and in the following year a Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) in Computing. As part of my PGCE dissertation, I designed and delivered a pilot scheme to teach JavaScript in playful ways. The learning materials were made available as open educational resources (OER) through Mozilla’s online teaching platform. OER are made available under a licence that allows others to reuse and repurpose them. Unfortunately, the constraints of the school context and the new curriculum hindered the kind of authentic activities that had first attracted me to teaching computing in schools. After completing my PGCE, I joined Manchester Metropolitan University in a role focusing on community education partnerships. This work provided opportunities to pursue creative, project-based approaches to teaching technology to young people and families, and ultimately led me to undertake this PhD study.

Connecting my experience to broader contextual themes

My experience detailed above informs the broad rationale of this thesis in several ways, including the need to explore pedagogical structures that facilitate collaborative production, to investigate dimensions of learning agency, and to examine the formation of community-based learning experiences in ways that are sustainable and resilient. This section briefly explores connections between my experience and these themes in turn.

Addressing pedagogies, the theme of tacit knowledge among practitioners, that is, knowledge that is embedded in practice but difficult to articulate, is a common challenge in education (Krátká, 2015). Such knowledge often operates through intuitive, experience-based judgement rather than explicit rules (Polanyi, 2009). Bruner (1999) calls these practices folk pedagogies. Rogoff (1994, p. 219) reflects that initial impressions of a chaotic learning environment in non-formal settings are misleading, stemming from a lack of understanding of the underlying structure of the mutual activities at play. The theme of surfacing tacit processes is relevant to the wider rationale of this study, as it addresses issues of structuring learning and overcoming barriers to facilitating non-formal CGD&P. As such, the research process requires precision in both reflection on and communication of practice, which I have observed in myself and others working in this field. This need informs the methodology of this study, as explored in Chapter 4.

Turning to outcomes for participants, early in the research process I reflected that while I had an intuitive sense of what a successful group session felt like within creative media project work, I lacked clear language to communicate this. In my experience of activist and community development settings, the motivations of social change, autonomy, and a broad sense of empowerment seemed appropriate as end goals for learners. As this research progressed, and became informed by existing literature, my interests coalesced around the development of multiple dimensions of agency within learning communities. To help reflect on this issue, this thesis engages with a complex and dynamic picture of participant agency, as explored in Chapter 3 in particular.

This thesis also continues a strand of my work advocating for community-based, replicable, and sustainable approaches to learning. Much of my previous work has revolved around community approaches to learning, whether at festivals, social centres, arts centres, or community workshops. Within these varied settings, I fulfilled roles organising and facilitating outreach events and online communications with the aim of bringing more people into community activities. Underlying this activity was a personal belief that the process would be beneficial both to the communities involved and to the people I was recruiting, a belief that continues to shape my practice. This research addresses an inequality of access to digital participatory culture with the understanding that such access has the potential to deliver significant benefits for participants. I have ensured that learning resources created as part of this research process are freely available, replicable, and sustainable OERs. These factors, along with a desire to use an authentic web-technology coding language and process, informed my rationale to create a novel toolset for the purposes of this study rather than adopt or adapt existing game making tools.

Rationale of home education settings as a site of research

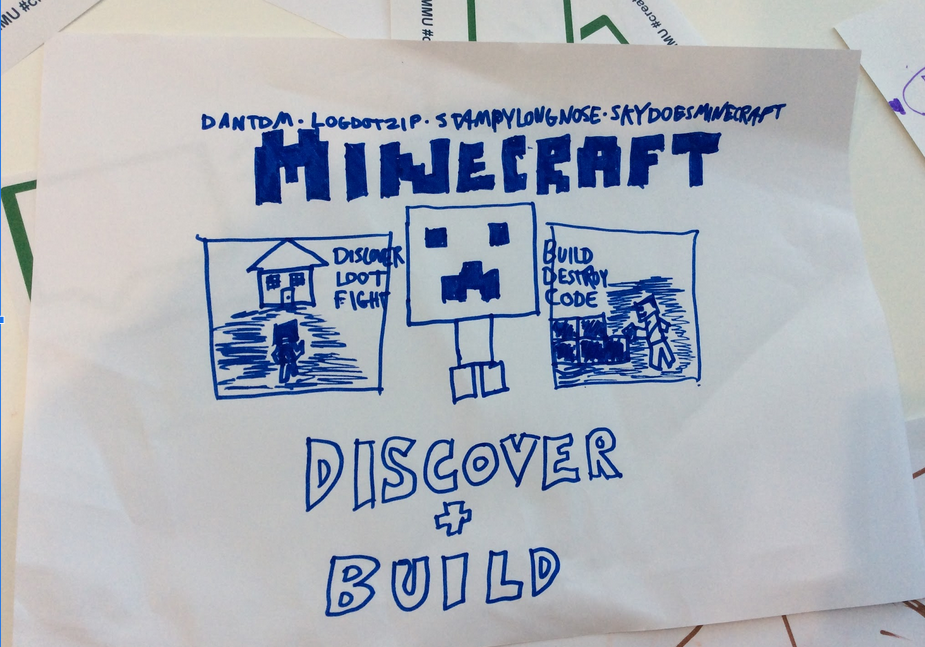

The involvement of home-educating families as the primary participants in this study, and game making as the principal activity, was the result of pragmatic factors. My engagement with game creation as an educator marked a significant shift in my personal practice. This new direction originated from a consultation with home educators undertaken as part of my university outreach and partnership work. At the consultation event, parents and children requested activities that drew on the children’s interest in digital games, asking whether we could teach computer coding through this interest. Minecraft was specifically mentioned as an example of a computer game involving creative processes. Figure 1.1 shows one of the outputs from this consultation. The names at the top of the image are those of YouTubers who create content related to Minecraft.

The contextual features outlined above align with other practical factors that made home-educating families suitable participants for this study. Research in school settings is sometimes hampered by issues such as timetable constraints and limited time for project work beyond the prescribed curriculum. These factors are largely absent when working with home-educating families. In addition, alignment with the interests and needs of participants was an important consideration in this collaboration with home educators, allowing for a stronger sense of reciprocity in the research process. This reciprocity also provided the foundation for the participatory and iterative design approach developed in the following chapters, where collaboration with families became central to shaping both the research process and its outcomes.

Summary problem statement of the thesis

Despite the growing recognition of CGD&P’s educational potential, effective pedagogies within this domain remain under-explored, particularly those suited to non-formal learning contexts (Denner, Campe and Werner, 2019; Gardner et al., 2022). Existing approaches do not fully integrate the collaborative, cultural, and community-based dynamics of these settings (Kafai and Burke, 2015), limiting opportunities for meaningful participation and the development of learner agency, prior knowledge of games, and an understanding of game design principles. Furthermore, because the abstract nature of programming can present barriers to learners (Papert and Turkle, 1990), there is a need for pedagogical strategies that connect abstract programming concepts with concrete design practices in CGD&P. This gap leaves practitioners with limited guidance on designing or facilitating activities that balance creative freedom with accessible entry points to learning. Addressing this challenge, the research focuses on non-formal learning contexts where these dynamics are most visible, in particular using gameplay design patterns (GDPs, see Glossary) as both a design and analytical framework to support inclusive and engaging game making practices across educational settings.

Theoretical framework, research objectives, and questions

Summary of the theoretical framework of this thesis

In choosing a theoretical approach that aligns with the goals of the research questions and my role as both practitioner and researcher, it is important to select a framework capable of addressing potential complications within the research process. Constructionism is a foundational guiding theory in game making studies (Papert, 1980), illustrated in particular by Kafai and colleagues, who outline the value of making constructionist games (Kafai and Burke, 2015) (see Glossary). Despite the value of these contributions to this domain of research, I agree with Ang et al. (2011, p. 539), who see value in constructionist framings of the pedagogical benefits of constructing tangible products in community settings but identify a limitation within constructionism, namely the absence of “a systematic framework for analysing the construction activities within a learning community”.

The focus of this research required a framework that could do the following: analyse the evolution of participant agency within the learning process, accommodate authentic learning contexts, conceptualise barriers to participation, and support a reciprocal approach to involving the community in design changes. To meet these needs, I have chosen cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) and supplemented it with specific techniques from design-based research (DBR). CHAT, as a theoretical framework, provides tools to examine how the past cultural activity of participants shapes present and emerging activity. It also offers powerful concepts for exploring a complex and dynamic picture of participant agency, aligning with the study’s focus on CGD&P as a means of participant empowerment within broader cultural contexts. DBR complements this by treating the research setting as both a site of inquiry and a site of iterative design, in which cycles of intervention and reflection respond to emergent contradictions within activity (see Chapter 3). This makes it particularly well suited to informal learning environments, where pedagogical approaches must adapt to participant needs while remaining grounded in authentic practice. In this way, DBR not only generates insights into learning processes but also produces practical resources and strategies that are directly usable by educators and communities. Chapter 3 explores the combined use of CHAT and DBR in greater depth in relation to these aims.

Research aim, objectives, and questions

This research explores how socio-cultural approaches, particularly cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT), can inform computer game design and programming (CGD&P) pedagogies. The study aims to enhance inclusive, engaging, and effective learning experiences within non-formal settings, with findings also intended for broader application. The overall aim of this study is best represented through the primary research question (PRQ) of this thesis: How can pedagogies that support CGD&P be enriched using socio-cultural approaches to enable inclusive learning in non-formal contexts?

To address this broad question, three sub-questions are posed:

- RQ1. What contradictions emerge during participation in CGD&P activities, and how can they be addressed through pedagogical change?

- RQ2. How can the use of a collection of gameplay design patterns support CGD&P, particularly in relation to abstract and concrete dimensions of existing pedagogies?

- RQ3. How can the development of repertoires and agency be supported in CGD&P, and what forms does this agency take?

The study is structured around three core objectives that align with the sub-questions above and with the overarching goal of enriching pedagogical approaches to CGD&P using activity theory as a socio-cultural framework. The first objective, linked to RQ1, is to create a novel pedagogy and toolset that responds to gaps in the current research landscape and to the limited resources available to practitioners. The study adapts my existing practice in facilitating web production to a new context, namely game making with text-based code within family learning. This includes the use of FLOSS and industry-standard web technologies, with the aim of enhancing the longevity, authenticity, and extensibility of the game making toolset. Through a design-based research approach, the study identifies and analyses the manifestations of contradictions within evolving CGD&P activities and explores their role in driving learning and the innovation of the resulting pedagogy and resources.

The second objective, linked to RQ2, is to develop a clear yet flexible pedagogy informed by gameplay design patterns (GDPs). Given that few studies provide detailed accounts of pedagogical approaches to supporting learners in the game-design process, this research explores how GDPs can function as mediating tools. The investigation considers their role in supporting the development of learner agency and in facilitating the appropriation of complex game-design knowledge within CGD&P learning environments.

The third objective, linked to RQ3, is to bring greater conceptual clarity to the social and cultural motivations underpinning novice participants’ engagement in CGD&P. The focus here is on understanding the development of learner agency through the lens of activity theory, and on examining how game-maker identities emerge within a novel community of practice. This objective explores how these identities can be nurtured across different learning communities and what pedagogical strategies best support this developmental process.

Chapter outline of the study

This introduction has covered key contextual, motivational, and theoretical considerations relevant to this study. This section now outlines the structure and indicative content of the chapters that follow. Chapter 2, the literature review, begins an exploration of the key themes and threads that are integral to the findings of this study. One of the challenges of this work is to communicate the technical aspects of the study to a non-specialist audience. To support this, a glossary of key technical terms is provided in the front matter, alongside the full table of contents. While the literature review further clarifies and situates these terms through engagement with existing research, a comprehensive glossary is also included as an appendix for reference. Key strands of the literature review include a review of existing studies on game making, an overview of the impact of constructionism on the field, a detailed exploration of varied game making pedagogies, particularly those using design patterns as a foundation, and a summary of game making programmes. The chapter concludes by revisiting the research questions and objectives of this thesis in relation to the gaps in existing research identified within it.

Chapter 3 details the theoretical framework used for this study, taking as its base the use of cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT). I also explain how the design-based research (DBR) approach aligns with the aims of the research questions and the use of concepts from third generation activity theory (3GAT). The chapter also outlines how CHAT and DBR are synthesised within the study, introducing formative interventions as a bridge between theoretical exploration and design practice. This chapter allows for discussion of concepts aligned with the theoretical framework, including the iterative, mutual, and emergent nature of the resources and processes, the process of identifying units of analysis, and transformative conceptions of agency.

Chapter 4 describes the methodology of the study. I outline and justify the process of data gathering using computer screen capture, 360-degree cameras, and other complementary methods. I explore the challenges of processing and analysing large amounts of research data and justify the resulting prioritisation of data. Chapter 4 also details the staged analytical process and the ethical and reflexive considerations that shaped data collection and interpretation. I also introduce the phases of learning delivery.

Chapter 5 takes the form of a process drawn from design-based research, a design narrative, to address Research Question 1 (RQ1). It provides a detailed account of the tools and pedagogical approaches that emerged through iterative cycles of design, implementation, and reflection. To explore emerging tensions in design in ways that communicate relevant context, the chapter outlines key contradictions within interrelated activity systems using the terminology of third generation activity theory (3GAT). Each section examines how these contradictions informed subsequent design responses and pedagogical refinements, highlighting the role of collaboration and feedback in shaping the evolving learning environment. The discussion begins by exploring themes of authenticity in tool use, the mutual evolution of design between researcher and participants, and the identification of initial barriers and corresponding interventions.

Chapter 6 focuses on the implementation and analysis of individual gameplay design patterns (GDPs), addressing Research Question 2 (RQ2). The chapter undertakes a systematic analysis of how GDPs were used by participants, drawing on detailed observations of practice captured through video recordings across the three planes of personal, interpersonal, and community activity. Through these analyses, the chapter demonstrates how GDPs functioned as mediating tools that connected abstract programming concepts with concrete design actions, supporting inclusive participation and creative expression. A concluding discussion explores the implications of these findings in relation to existing research of computational fluency and theoretical perspectives on mediation and design thinking.

Chapter 7 extends the analysis of findings from Chapter 6, situating them within existing research on programming pedagogies and the interplay between abstract and concrete dimensions of computing education. The chapter then addresses gaps in the current landscape of CGD&P research by examining participants’ development of agency through game making, thereby addressing Research Question 3 (RQ3). It discusses the characteristics of an inclusive pedagogical environment that enabled participants to become part of an emerging community of game makers, and explores the role of design interventions in supporting and nurturing the expression of learner identities. The chapter also considers how cultural repertoires and relational dynamics shaped the ways agency was enacted across personal, interpersonal, and community planes of activity. It concludes by summarising findings for a broad audience, focusing particularly on processes that facilitate relational agency and sustained participation.

Chapter 8 concludes the thesis with a discussion of the significance of the findings in relation to existing research and identifies directions for future work. It provides a synthesis of the study as a whole, reflecting on how the research questions have been addressed and considering the wider implications for practice, research, and policy. The chapter also outlines potential avenues for further investigation and ends with a reflection on the significance of the study within today’s changing educational landscape and in relation to my own practice.

In summary, this introduction has outlined the core motivations for this study and summarised key relevant contextual domains. It has also highlighted the complexities of and introduced the structure of the thesis, emphasising central strands such as authenticity, barriers to participation, and inclusive pedagogical strategies. The subsequent chapter will provide a detailed examination of pertinent research on effective pedagogies and essential theoretical concepts needed to follow this study. This review, in particular, clarifies crucial frameworks underpinning the study’s first research question and establishes the foundation for the later exploration of how design based research and cultural-historical activity theory are employed to address the research questions.

Chapter References

Ang, C.S., Zaphiris, P. and Wilson, S. (2011) ‘A case study analysis of a constructionist knowledge building community with activity theory’, Behaviour & Information Technology, 30(5), pp. 537–554. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2010.490921.

Avci, H., Baams, L. and Kretschmer, T. (2025) ‘A systematic review of social media use and adolescent identity development’, Adolescent Research Review, 10(2), pp. 219–236. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-024-00251-1.

Bermingham, S. et al. (2013) ‘Approaches to collaborative game-making for fostering 21st century skills’, in Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Games Based Learning. Porto: API.

Bevan, B., Petrich, M. and Wilkinson, K. (2014) ‘Tinkering is serious play’, Educational Leadership, 72(4), pp. 28–33.

Blikstein, P. (2018) ‘Maker movement in education: History and prospects’, in M.J. De Vries (ed.) Handbook of Technology Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing (Springer International Handbooks of Education), pp. 419–437. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44687-5_33.

Boyle, J. and Kao, W.-C. (eds) (2017) The retro-futurism of cuteness. punctum books. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21983/P3.0188.1.00.

Bruner, J. (1999) Folk pedagogies. London: Paul Chapman Educational Publishing.

Buechley, L. et al. (2008) ‘The LilyPad Arduino: Using computational textiles to investigate engagement, aesthetics, and diversity in computer science education’, in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Florence, Italy: ACM, pp. 423–432. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357123.

Chesterman, M. (2015) Webmaking using JavaScript to promote student engagement and constructivist learning approaches at KS3. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20180831105358/http://digitalducks.org/blog/project-report-webmaking/ (Accessed: 19 March 2016).

Connolly, S.E., Constable, H.L. and Mullally, S.L. (2023) ‘School distress and the school attendance crisis: a story dominated by neurodivergence and unmet need’, Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, p. 1237052. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1237052.

Denner, J. et al. (2014) ‘Beyond stereotypes of gender and gaming: Video games made by middle school students’, in M.C. Angelides and H. Agius (eds) Handbook of Digital Games. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 667–688. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118796443.ch25.

Denner, J. and Campe, S. (2008) ‘What do girls want? What games made by girls can tell us’, Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New perspectives on gender and gaming, pp. 128–144.

Denner, J., Campe, S. and Werner, L. (2019) ‘Does computer game design and programming benefit children? A meta-synthesis of research’, ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 19(3), pp. 1–35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3277565.

Department for Education (2013) ‘National curriculum in England: Computing programmes of study’, Retrieved July, 16, p. 2014.

DiSalvo, B. et al. (2014) ‘Saving face while geeking out: video game testing as a justification for learning computer science’, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23(3), pp. 272–315. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2014.893434.

DiSalvo, B.J. et al. (2009) ‘Glitch game testers: African American men breaking open the console’, in Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory., p. 7.

DiSalvo, B.J., Crowley, K. and Norwood, R. (2008) ‘Digital games and young black men’, Games and Culture, 3(2), pp. 131–141. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412008314130.

Doroudi, S. and Ahmad, Y. (2023) ‘The relevance of Ivan Illich’s learning webs 50 years on’, in Proceedings of the Tenth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (L@S ’23), pp. 99–109. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3573051.3593386.

Edwards, D. et al. (2023) ‘The STEM pipeline: Pathways and influences on participation and achievement of equity groups’, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 45(2), pp. 206–222. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2023.2180169.

Eklund, L. and Helmersson Bergmark, K. (2013) ‘Parental mediation of digital gaming and internet use’, in, pp. 63–70. Available at: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-90033 (Accessed: 22 May 2025).

Engelstätter, B. and Ward, M.R. (2022) ‘Video games become more mainstream’, Entertainment Computing, 42, p. 100494. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2022.100494.

Eshach, H. (2007) ‘Bridging in-school and out-of-school learning: Formal, non-formal, and informal education’, Journal of Science Education and Technology, 16(2), pp. 171–190. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-006-9027-1.

Fensham-Smith, A.J. (2021) ‘Invisible pedagogies in home education: Freedom, power and control’, Journal of Pedagogy, 12(1), pp. 5–27. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2021-0001.

Galen, J.V. and Pitman, M.A. (1991) Home schooling: Political, historical, and pedagogical perspectives. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Garda, M.B. (2014) ‘Nostalgia in retro game design’, in Proceedings of the 2013 DiGRA International Conference: DeFragging Game Studies. DiGRA. Available at: http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/paper_310.pdf.

Gardner, T. et al. (2022) ‘What do we know about computing education for K-12 in non-formal settings? A systematic literature review of recent research’, in Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research - Volume 1. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery (ICER ’22), pp. 264–281. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3501385.3543960.

Gee, J.P. (2004) What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. 1. paperback ed. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan (Education).

Gerlich, M. (2025) ‘AI tools in society: Impacts on cognitive offloading and the future of critical thinking’, Societies, 15(1), p. 6. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15010006.

Gomes, A. and Mendes, A.J. (2007) ‘Learning to program: Difficulties and solutions’, in Proceedings of the international conference on engineering Education. ICEE.

Gove, M. (2012) Michael Gove speech at the BETT Show 2012, GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/michael-gove-speech-at-the-bett-show-2012 (Accessed: 11 July 2024).

Gray, P. and Riley, G. (2013) ‘The challenges and benefits of unschooling, according to 232 families who have chosen that route’, Journal of Unschooling and Alternative Learning, 7(14).

Heritage, R. (2008) ‘Video-activist citizenship and the Undercurrents media project: A british case-study in alternative media’, in Alternative Media and the Politics of Resistance: Perspectives and Challenges. Ljublana: Peace Institute. Ljubljana: Peace Institute, pp. 139–161.

Holmes, J. and Beeck, L. van (2023) ‘The role of the STEM Video Game Challenge in the pipeline to tertiary STEM education’, Proceedings of The Australian Conference on Science and Mathematics Education, pp. 37–37. Available at: https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/IISME/article/view/17439 (Accessed: 22 May 2025).

Illich, I. (1971) Deschooling society. 1st ed. New York: Harper & Row (World perspectives, v. 44).

Ito, M. et al. (2013) Connected learning: An agenda for research and design. Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Itō, M. (ed.) (2009) Living and learning with new media: Summary of findings from the digital youth project. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press (The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation reports on digital media and learning).

Itō, M. et al. (eds) (2010) Hanging out, messing around, and geeking out: Kids living and learning with new media. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press (The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation series on digital media and learning).

João, P. et al. (2019) ‘A cross-analysis of block-based and visual programming apps with computer science student-teachers’, Education Sciences, 9(3), p. 181. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030181.

Juul, J. (2012) A casual revolution: reinventing video games and their players. MIT Press.

Kafai, Y. and Burke, Q. (2014) ‘Beyond game design for broadening participation: Building new clubhouses of computing for girls’, in Proceedings of Gender and IT Appropriation. Science and Practice on Dialogue - Forum for Interdisciplinary Exchange. Siegen, Germany: European Society for Socially Embedded Technologies (Gender IT ’14), pp. 21:21–21:28. Available at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2670296.2670301 (Accessed: 18 July 2018).

Kafai, Y. and Burke, Q. (2015) ‘Constructionist gaming: Understanding the benefits of making games for learning’, Educational Psychologist, 50(4), pp. 313–334. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2015.1124022.

Kafai, Y., Richard, G.T. and Tynes, B.M. (2017) Diversifying barbie and mortal kombat: Intersectional perspectives and inclusive designs in gaming. Pittsburgh: ETC Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/6686738.

Kemp, P. et al. (2024) The future of computing education: Considerations for policy, curriculum and practice. King’s College London and University of Reading.

Krátká, J. (2015) ‘Tacit knowledge in stories of expert teachers’, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 171, pp. 837–846. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.199.

Kuntsman, A. and Miyake, E. (2022) Paradoxes of digital disengagement: In search of the opt-out button. University of Westminster Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.16997/book61.

Lessig, L. (2004) Free culture: How big media uses technology and the law to lock down culture and control creativity. New York: Penguin Press.

Lessig, L. (2009) Remix : Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Livingstone, I. and Hope, A. (2011) Next Gen: Transforming the UK into the world’s leading talent hub for the video games and visual effects industries. London: National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA).

Livingstone, S.M. and Blum-Ross, A. (2020) Parenting for a digital future: How hopes and fears about technology shape children’s lives. Oxford University Press.

Luther, K. et al. (2010) ‘Why it works (when it works): Success factors in online creative collaboration’, in Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work. New York, NY, USA: ACM (GROUP ’10), pp. 1–10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/1880071.1880073.

Margolis, J. (2008) Stuck in the shallow end: Education, race, and computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McKay, G. (1998) DiY culture: Party and protest in nineties’ britain. Verso.

Moje, E.B. et al. (2004) ‘Working toward third space in content area literacy: An examination of everyday funds of knowledge and discourse’, Reading Research Quarterly, 39(1), pp. 38–70. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.39.1.4.

Mozilla Foundation (2014) Webmaker Whitepaper. Available at: https://wiki.mozilla.org/Webmaker/Whitepaper (Accessed: 9 May 2015).

Nikken, P. and Jansz, J. (2006) ‘Parental mediation of children’s videogame playing: A comparison of the reports by parents and children’, Learning, Media and Technology, 31(2), pp. 181–202. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17439880600756803.

O’Hagan, S., Bond, C. and Hebron, J. (2021) ‘What do we know about home education and autism? A thematic synthesis review’, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 80, p. 101711. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101711.

Papert, S. (1980) Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books.

Papert, S. (1993) The children’s machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. New York: BasicBooks.

Papert, S. and Turkle, S. (1990) ‘Epistemological pluralism and the revaluation of the concrete’, Signs, 16(1). Available at: http://www.papert.org/articles/EpistemologicalPluralism.html (Accessed: 1 November 2017).

Pelletier, C. (2008) ‘Gaming in context: how young people construct their gendered identities in playing and making games’, in Y.B. Kafai et al. (eds) Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 145–159. Available at: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1561023/ (Accessed: 19 July 2018).

Peppler, K., Danish, J.A. and Phelps, D. (2013) ‘Collaborative gaming: Teaching children about complex systems and collective behavior’, Simulation & Gaming, 44(5), pp. 683–705. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878113501462.

Pickard, V.W. (2006) ‘United yet autonomous: Indymedia and the struggle to sustain a radical democratic network’, Media, Culture & Society, 28(3), pp. 315–336. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443706061685.

Polanyi, M. (2009) ‘The tacit dimension’, in Knowledge in organisations. Routledge, pp. 135–146.

Preston, C. (2013) ‘Re-engineering the ICT profession: A global call for collective action’, ACM Inroads, 4(2), pp. 42–49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/2465085.2465099.

Queirós, R., Pinto, M. and Terroso, T. (2021) ‘User experience evaluation in a code playground’, OASIcs, Volume 91, ICPEC 2021. Edited by P.R. Henriques et al., 91, pp. 17:1–17:9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4230/OASICS.ICPEC.2021.17.

Rahmat, M. et al. (2012) ‘Major problems in basic programming that influence student performance’, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 59, pp. 287–296. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.277.

Resnick, M. (2002) Rethinking learning in the digital age. Oxford: World Economic Forum.

Resnick, M. et al. (2009) ‘Scratch: programming for all’, Communications of the ACM, 52(11), p. 60. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/1592761.1592779.

Resnick, M. (2017) Lifelong kindergarten: Cultivating creativity through projects, passion, peers, and play. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Resnick, M. (2018) ‘Computational fluency’, Medium, 16 September. Available at: https://mres.medium.com/computational-fluency-776143c8d725 (Accessed: 9 July 2024).

Resnick, M. and Rusk, N. (1996) ‘The computer clubhouse: Preparing for life in a digital world’, IBM Systems Journal, 35(3.4), pp. 431–439. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1147/sj.353.0431.

Resnick, M. and Rusk, N. (2020) ‘Coding at a crossroads’, Communications of the ACM, 63(11), pp. 120–127. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3375546.

Robertson, J. and Nicholson, K. (2007) ‘Adventure author: A learning environment to support creative design’, in Proceedings of the 6th international conference on Interaction design and children. ACM, pp. 37–44. Available at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1297285 (Accessed: 19 June 2017).

Rogoff, B. (1994) ‘Developing understanding of the idea of communities of learners’, Mind, culture, and activity, 1(4), pp. 209–229.

Rogoff, B. (1995) ‘Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: Participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship’, in Sociocultural studies of mind. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press (Learning in doing: Social, cognitive, and computational aspects), pp. 139–164.

Rogoff, B. et al. (2016) ‘The organization of informal learning’, Review of Research in Education, 40(1), pp. 356–401. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X16680994.

Rothermel, P. (2003) ‘Can we classify motives for home education?’, Evaluation & Research in Education, 17(2-3), pp. 74–89. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09500790308668293.

Ruckenstein, M. (2023) The feel of algorithms. Univ of California Press.

Rushkoff, D. (2010) Program or be programmed: Ten commands for a digital age. New York: OR Books.

Schmidt, E. (2011) Eric Schmidt’s MacTaggart lecture, The Guardian. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/media/interactive/2011/aug/26/eric-schmidt-mactaggart-lecture-full-text (Accessed: 12 July 2024).

Sefton-Green, J. (2006) Literature review in informal learning with technology outside school. Bristol: Futurelab, p. 43.

Sefton-Green, J. (2013) Mapping digital makers: A review exploring everyday creativity, learning lives and the digital. Available at: http://www.nominettrust.org.uk/ (Accessed: 18 December 2018).

Sefton-Green, J. and Erstad, O. (2012) ‘Identity, community, and learning lives in the digital age’, in O. Erstad and J. Sefton-Green (eds) Identity, Community, and Learning Lives in the Digital Age. 1st edn. Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139026239.001.

Sentance, S., Waite, J. and Kallia, M. (2019) ‘Teaching computer programming with PRIMM: A sociocultural perspective’, Computer Science Education, 29(2-3), pp. 136–176. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/08993408.2019.1608781.

Shea, P. (2019) ‘Hacker agency and the Raspberry Pi: Informal education and social innovation in a Belfast Makerspace’, in Making our world: The hacker and maker movements in context. Peter Lang US.

Sheridan, K. et al. (2014) ‘Learning in the making: a comparative case study of three makerspaces’, Harvard Educational Review, 84(4), pp. 505–531. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.4.brr34733723j648u.

Syvertsen, T. and Enli, G. (2020) ‘Digital detox: Media resistance and the promise of authenticity’, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 26(5-6), pp. 1269–1283. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856519847325.

The Royal Society (2012) Shut down or restart? The way forward for computing in UK schools. London: The Royal Society. Available at: https://royalsociety.org/~/media/education/computing-in-schools/2012-01-12-computing-in-schools.pdf (Accessed: 12 October 2014).

Thorne, M. (2015) ‘Clubs: Web literacy basics curriculum’, Mozilla Clubs. Available at: https://michellethorne.cc/2015/03/clubs-web-literacy-basics-curriculum/ (Accessed: 11 July 2024).

Thumlert, K., de Castell, S. and Jenson, J. (2018) ‘Learning through game design: a production pedagogy’, in Proceedings of the 12th european conference on game-based learning. ACPI.

Twining, P. (2013) ‘We were consulted’, EdFutures. Available at: https://edfutures.net/index.php?title=We_were_consulted (Accessed: 11 July 2024).

Vossoughi, S. and Bevan, B. (2015) ‘Making and tinkering: A review of the literature’. Available at: http://www.sesp.northwestern.edu/docs/publications/1926024546baba2b73c7.pdf (Accessed: 9 May 2015).

Vossoughi, S., Hooper, P.K. and Escudé, M. (2016) ‘Making through the lens of culture and power: Toward transformative visions for educational equity’, Harvard Educational Review, 86(2), pp. 206–232. Available at: http://www.hepgjournals.org/doi/abs/10.17763/0017-8055.86.2.206 (Accessed: 14 October 2017).

Waite, J. (2017) Pedagogy in teaching computer science in schools: a literature review. London: The Royal Society. Available at: https://royalsociety.org/%7E/media/policy/projects/computing-education/literature-review-pedagogy-in-teaching.pdf.

Werquin, P. (2009) ‘Recognition of non-formal and informal learning in OECD countries: An overview of some key issues’, Recognition of Non-formal and Informal Learning in OECD Countries: an Overview of Some Key Issues [Preprint], (03/2009). Available at: https://doi.org/10.3278/REP0903W011.

Yu, J. and Roque, R. (2018) ‘A survey of computational kits for young children’, in Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Interaction Design and Children. Trondheim, Norway: ACM Press, pp. 289–299. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/3202185.3202738.

-

Here the term remixing describes a process of using an existing code project created by another community user as a basis for a new creation. ↩︎

-

See http://itch.io for an example of a vibrant game creation and sharing community with many examples of retro games created by amateurs. ↩︎

-

Available at http://archive.flossmanuals.net/an-open-web/ ↩︎